Chelomey’s Kosmoplan and Raketoplan

Until the late 1950s the OKB-52 of Vladimir Chelomey was a relatively minor design bureau specializing in anti-ship cruise missiles. However, by the end of the decade Chelomey’s star began to rise, something that he owed at least partially to the fact that Khrushchov’s son Sergey began working at the design bureau in 1958. Brimming with ambition, Chelomey set his sights on intercontinental missiles and space projects. From the outset he focused his research on winged spacecraft, not just for missions in Earth orbit, but also for flights to the Moon and planets.

In 1958-1959 OKB-52 began working on two projects called Kosmoplan and Raketoplan. Kosmoplan was a rather futuristically looking family of spacecraft primarily designed to fly to the Moon, Mars, and Venus and then return to Earth. During re-entry the winged landing vehicle would be protected from thermal stresses by a jettisonable container shaped somewhat like a furled umbrella and it would land on a conventional runway using turbojet engines. One early version of the Kosmoplan was also intended for military reconnaissance missions in low Earth orbit. Initial Kosmoplan missions would be automated, with the eventual goal being to switch to piloted flights, first for the Earth-orbital version and later for the deep – space versions.

Raketoplan was initially conceived as a suborbital vehicle to carry passengers and cargo over intercontinental distances and, more importantly, to perform bombing missions. Launched by a conventional rocket or a winged fly-back booster, it would perform suborbital ballistic flights with aerodynamic braking, maneuvering and landing on a runway using turbojets. Two versions were studied, one for a range of 8,000 km and the other for a range of 40,000 km.

|

Chelomey received official support for the projects with a government and party decree of 23 June 1960, which saw a clear shift in emphasis from civilian to military space projects compared with the space plan outlined in the December 1959 decree. It

called for the development of two unmanned deep-space versions of the Kosmoplan (“Object K”) by 1965-1966, one with a mass of 10-12 tons and the other with a mass of 25 tons. The vehicles were to be launched by a new Chelomey rocket with a launch mass of 600 tons. Raketoplan (“Object R”) was now eyed as an orbital spaceplane with a mass of 10-12 tons. An unmanned version would be ready in 1960-1961, a piloted variant in 1963-1965, and an anti-satellite version in 1962-1964 [22].

However, these goals turned out to be overly ambitious and another government decree on 13 May 1961 ordered OKB-52 to limit this work to a piloted version of the Raketoplan for military missions in Earth orbit and for deep-space missions. By 1963 engineers had completed the preliminary design for four variants of such a vehicle: two single-seat Earth-orbital versions for anti-satellite and bombing missions, a two – seat scientific spacecraft for circumlunar flight, and a seven-seat passenger ballistic spacecraft for intercontinental ranges. The first three were to be launched by the Chelomey bureau’s UR-500/Proton, the fourth by the UR-200. Despite the name Raketoplan, the circumlunar spacecraft appears to have been a wingless vehicle for a ballistic re-entry from lunar distances, one that would later evolve into a vehicle called LK-1 that had a shape reminiscent of the US Gemini capsule.

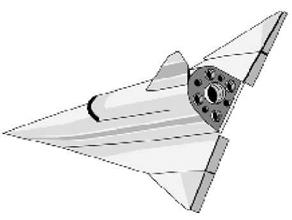

By early 1964 the Raketoplan project was left with only military goals, namely orbital reconnaissance and anti-satellite missions. At this time OKB-52 was planning two versions, the unmanned R-1 and the manned R-2, both weighing 6.3 tons. The R-1 was a model of the piloted version designed to test all essential systems in orbit. The R-2, manned by a single pilot, would fly 24-hour missions in a nominal orbit of 160 x 290 km.

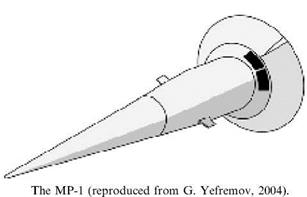

Two test vehicles were developed in the framework of the Raketoplan project to test heat shield materials, flight control systems, and maneuvering characteristics at hypersonic speeds. One was a 1,750 kg model called MP-1, a cone-shaped vehicle with two graphite rudders and a set of speed brakes at the base resembling an unfurled umbrella. The MP-1 was launched by an R-12 missile from the Vladimirovka test site near Kapustin Yar (Volgograd region) on 27 December 1961. Having reached a

|

The R-2 Raketoplan (source: Dennis Hassfeld). |

|

|

maximum altitude of 405 km, it successfully re-entered the atmosphere at a speed of 3,800m/s and safely landed on three parachutes 1,880 km downrange. This marked the first ever re-entry test of an aerodynamically controlled vehicle. It came about two years before the US Air Force began similar flights under the so-called START program.

The other vehicle was named M-12 and looked quite similar to its predecessor, except that the umbrella-shaped braking panels were replaced by four titanium rudders. Using the same missile and launch site as the MP-1, the 1,700 kg M-12 was launched on 21 March 1963, but was lost during re-entry, probably because of a problem with its heat shield. The data obtained during the tests were also applicable to OKB-52’s research on maneuverable warheads. This was particularly the case for the M-12, which was seen as a subscale model of the AB-200 warhead. The MP-1 and M-12 were significant in that they were the only hardware ever launched in support of the multitude of Soviet spaceplane projects conceived in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The Raketoplan project was discontinued in 1964-1965. There appear to have been several reasons for this. First, Chelomey lost much of his political support when Khrushchov was overthrown and replaced by Brezhnev in October 1964. Second, the design bureau was heavily involved in other manned space projects such as the LK-1 circumlunar program and the Almaz military space station. Finally, many of the military objectives planned for Raketoplan were already being or about to be performed by unmanned satellites such as OKB-1’s Zenit (for photographic reconnaissance) and OKB-52’s own US (for ocean reconnaissance) and IS (for anti-satellite missions). The whole research database on Raketoplan along with a number of Chelomey’s specialists were transferred to the Mikoyan design bureau [23].