Myasishchev’s Projects 46 and 48

Vladimir Myasishchev’s OKB-23 (situated in the Moscow suburb of Fili) was mainly engaged in the development of long-range strategic bombers, but branched out into cruise missiles with the M-40/Buran project in 1954-1957 and also did considerable research on spaceplanes even before Tsybin had started his PKA project. Unfortunately, most of the archival materials related to Myasishchev’s spaceplane projects have not been preserved, making it difficult to piece together their history. According to Russian historians Myasishchev, inspired by plans for the X-15 and US boost – glide concepts, began spaceplane research “on his own initiative’’ as early as 1956 under a program named Project 46. Also involved in the research were the NII-1 and NII-4 research institutes.

By 1957 he came to the conclusion it would be feasible in the short run to develop a reusable vehicle called a “satelloid’’ or “intercontinental rocket plane’’. Its primary goal would be to conduct strategic reconnaissance over enemy territory without the risk of being shot down by anti-aircraft defense means. Such missions would last 3 to 4 hours, with the spaceplane using radar and both optical and infrared photographic equipment to detect troop movements and spot enemy aircraft and missiles. Included

|

Vladimir Myasishchev. |

|

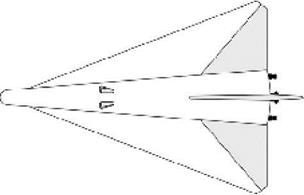

Project 46 spaceplane (reproduced from A. Bruk, 2001). |

in the early warning network would be high-orbiting relay satellites. Later goals were to send vehicles of this type on bombing missions or to destroy enemy missiles and satellites. A reconnaissance version was expected to be ready by 1963 and a combined reconnaissance/bombing version was planned for 1964-1965. Myasishchev is said to have presented his ideas for spaceplanes during a visit to OKB-23 by Khrushchov in August 1958, but the Soviet leader was unimpressed, telling Myasishchev to stick to the field of aviation and leave rocket-related matters to others.

Undeterred by Khrushchov’s scepticism, OKB-23 pressed on with its spaceplane research. By April 1959 the bureau had worked out plans for a 10-ton rocket plane flying between altitudes of 80 and 150 km and capable of increasing orbital altitude by 100 km (to a maximum of 250 km) and changing orbital inclination by 3°. As Dyna-Soar, it was envisaged as a “boost-glide” system, being launched into orbit by a conventional ballistic rocket and then gliding back to a horizontal runway landing. The launch vehicle was to be an upgraded three-stage version of Korolyov’s R-7 missile. The third stage apparently consisted of four “boost engines’’ drawing propellant from four jettisonable tanks mounted on the spaceplane itself. In April 1960 Myasishchev revised his plans and was now aiming for a 6-ton vehicle flying in 600 km orbits and capable of performing inclination-changing maneuvers of as much

|

6 |

.

Meanwhile, OKB-23 was tasked with the development of another manned space vehicle by a government and party decree (nr. 1388-618) issued on 10 December 1959. This decree, considered to be the first macro-policy statement on the Soviet space program, encompassed a wide range of space projects. Myasishchev’s bureau in particular was assigned to develop a manned vehicle capable of ensuring “a reliable link’’ between the ground and “heavy satellites’’. Known as Project 48, this appears to have been an early version of a transportation system for space stations, although it was supposed to solve defense-related tasks as well. It was only the second piloted space project to be officially approved by a party/government decree after Vostok. Work on the project got underway after orders from the State Committee of Aviation Technology (GKAT) on 7 January and 4 March 1960.

|

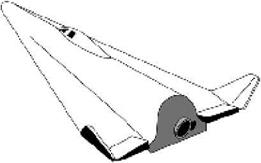

48-2 spaceplane (reproduced from A. Bruk, 2001).

Weighing no more than 4.5 tons, the spacecraft was to be launched into a circular 400 km orbit by an R-7 based launch vehicle and stay in orbit anywhere from 5 to 27 hours. Re-entry through the atmosphere was to consist of a ballistic and a “controlled gliding” phase, reducing deceleration forces to no more than 3-4g. This required an aerodynamic shape providing at least some lift and ruled out a Vostok – type spherical design. Thermal protection was to be provided by ceramic tiles and/or by super-cold liquid metals circulating under the spacecraft’s skin.

Myasishchev’s team came up with four possible designs to meet these requirements, each capable of carrying two men. Vehicle 48-1 (launch mass 4.5 tons) had a cone-shaped fuselage with highly swept delta wings (79°) and fins on the wings and fuselage to provide braking during re-entry. The crew cabin was located in the back. Both the fins and the glider’s engine compartment were to be jettisoned when the spaceplane had decelerated to a speed of Mach 5. Vehicle 48-2 (launch mass 4.3 tons) had a cylindrical fuselage with delta wings (leading edge sweepback of 65°) and small canards in the front. There were vertical tails both on top of and under the fuselage. The crew cabin was situated in the middle and the spaceplane was outfitted with a non-jettisonable engine compartment. The two other schemes envisaged a Mercury/ Gemini look-alike inverted cone with a rotor for a helicopter-type landing (48-3) and a conically shaped spacecraft for a parachute landing (48-4). Missions of the two-man ship were to be preceded by test flights of a single-seater spaceplane to demonstrate

|

One version of the VKA-23 spaceplane (reproduced from A. Bruk, 2001). |

the functioning of life support systems and test the “gliding re-entry” technique. The proposals were reviewed at a meeting of leading aviation specialists on 8 April I960, but no consensus was reached on the way to go forward.

There was yet another OKB-23 proposal for a single-seater spaceplane, which Myasishchev historians also link to Project 48, although it does not appear to have been the aforementioned one-man demonstration vehicle. It has been referred to as VKA-23 (VKA standing for “Aerospace Apparatus” and “23” referring to the name of the design bureau) and was the brainchild of OKB-23 designers L. Selyakov and G. Dermichov, who had originally presented it to NII-1 chief Mstislav Keldysh. Two versions of the delta-wing VKA-23 were studied between March and September 1960, one with a single fin at the rear (launch mass between 3.5 and 4.1 tons, length 9.4m) and one with two fins at the tips of the wings (launch mass between 3.6 and 4.5 tons, length 9.0 m).

The VKA-23 was to be launched either by an R-7 based rocket or a much more powerful rocket developed in-house under the so-called Project 47. In a launch emergency, the pilot could eject from the vehicle up to an altitude of 11 km, higher than that the entire vehicle would be separated from the rocket. The VKA-23 was supposed to borrow some elements from the Vostok spacecraft such as the Chayka orientation system and the Zarya communication system. Thermal protection was provided by ultra lightweight ceramic foam tiles very similar in shape to the ones later used by the US Space Shuttle and Buran. The leading edges of the wings were protected by a thick layer of siliconized graphite. A small turbojet engine was to give the ship extra maneuverability during re-entry. Just like the Vostok cosmonauts, the pilot was not supposed to land inside the ship, but eject at an altitude of about 8 km, with the spacecraft itself making an automatic landing on skids.

Although Project 48 had received the official nod with the party/government decree of December 1959, it was no longer mentioned in an even bigger space decree released on 23 June 1960. Actually, OKB-23 was counting its final days, falling victim to Khrushchov’s policy of downsizing aviation in favor of missiles. In October 1960 Myasishchev’s design bureau became Branch Nr. 1 of the OKB-52 design bureau of Vladimir Chelomey and was assigned to various missile, rocket, and spacecraft projects. Myasishchev was named head of TsAGI, but in 1967 was placed in charge of the EMZ design bureau, which would go on to play a vital role in the Buran program [20].