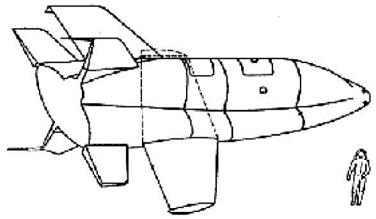

Tsybin’s PKA

Nevertheless, Korolyov, a veteran of several rocket plane projects in the 1930s and 1940s, did not abandon the idea of winged piloted spaceflight. Outlining their ideas on the future of spaceflight in a joint letter to the government on 5 July 1958, Korolyov and his associate Mikhail Tikhonravov called for developing a manned space capsule in the 1958-1960 timeframe and then to design a manned vehicle “with a gliding return profile” in 1959-1965 [16].

Preoccupied with work on the R-7 rocket and the first satellites, Korolyov turned to a befriended aircraft designer to start preliminary research on a manned space – plane. This was Pavel V. Tsybin, who had got acquainted with Korolyov back in the early 1930s while building gliders. After leading research on the LL “flying laboratories” in the late 1940s, Tsybin worked on missiles at N11-88 from 1949 to 1951 and subsequently became involved in the design of the air-launched Kometa anti-ship cruise missile at the Mikoyan design bureau. Finally, in May 1955 Tsybin was placed in charge of a newly founded design bureau called OKB-256, situated in Podberyozye, which in 1956 became part of the newly founded city of Dubna. Its primary assignment was to create the RS, a long-range bomber powered by supersonic ramjet engines, although by mid-1956 the focus had shifted to a supersonic reconnaissance aircraft named RSR.

Sometime later, presumably in 1958, Korolyov proposed Tsybin to design a small winged spaceship that could be orbited by an R-7 based rocket. Tsybin’s team readily set to work, assisted by specialists from OKB-1. What they came up with was a vehicle called PKA (for “Gliding Space Apparatus’’), which because of its shape was also nicknamed Lapotok (“little bast shoe’’).

Having a launch mass of 3.5 tons, the one-man spaceplane was to be placed into a circular 300 km orbit by a Vostok rocket for missions lasting up to 24-27 hours. Built into the fuselage was a small pressurized cabin with a control panel, life support systems, and three windows, one of them for an astronavigation system. In case of a launch abort, the pilot could eject from the cabin up to an altitude of 10 km and in an emergency at higher altitudes the entire spaceplane would be separated from the rocket. Located behind the cabin was a pressurized instrument compartment with on-

|

Pavel Tsybin. |

orbit and re-entry support systems. The spaceplane also had a detachable engine compartment with two 2,350 kg thrust nitric acid/kerosene engines, one for on-orbit maneuvers and the other for the deorbit burn. Also on this compartment were an infrared vertical sensor and a thermal control system using radiators. The dry mass of the engine unit was 350 kg and the propellant mass at launch was 430 kg. For orientation in orbit and during the early stages of re-entry the ship used small hydrogen peroxide thrusters.

The deorbit, re-entry, and landing phase was to last up to 90 minutes. After the deorbit burn the engine compartment was to be separated at an altitude of 90 km. During re-entry the spaceplane’s steel fuselage was protected from the high temperatures by a heat shield consisting of a 100 mm thick organic silicon layer and a 70 mm thick fibre layer as well as by special air ducts to cool the outside structure. Places with maximum heat exposure such as the nose of the heat shield and the leading edges of the two elevons and the tail were to be cooled with the help of liquid lithium. During maximum heating the angle of attack was 55 to 60°. At an altitude of 20 km, having reduced its speed to 500-600 m/s, the PKA would deploy two wings with a span of 7.5 m and an area of 8.7 m2, which until then had remained folded back to protect them against the highest temperatures during re-entry. The spaceplane was to land on a dirt runway using a skid landing gear. Landing speed was 180-200 km/h and landing mass was 2.6 tons.

The preliminary design (“draft plan’’ in Russian terminology) for the PKA was officially approved by Tsybin on 17 May 1959 and the following day Korolyov sent a letter to the State Committee of Defense Technology (GKOT, the former Ministry of Armaments) with the request to include the spaceplane in its long-range plans and assign OKB-256 to the project as the lead organization [17]. However, wind tunnel tests conducted at the Central Aerohydrodynamics Institute (TsAGI) showed that the PKA would be exposed to much higher temperatures than expected (up to 1,500°C), requiring significant changes to the heat shield. Moreover, it turned out

|

The PKA spaceplane (source: Igor Afanasyev). |

that the use of liquid lithium to cool the hottest parts of the fuselage would make the design much heavier and more complex than anticipated [18].

Tsybin invited specialists of the All-Union Institute of Aviation Materials (VIAM) to deal with these issues, but by the end of 1959 clouds were gathering not only over the PKA, but over Tsybin’s design bureau as well. The RS supersonic strategic bomber had been canceled in the wake of the Soviet Union’s early ICBM successes and in October 1959 OKB-256 was absorbed by Myasishchev’s OKB-23. When OKB-23 in turn became a branch of Vladimir Chelomey’s OKB-52 in late I960, Tsybin returned to Korolyov’s OKB-1, where he would eventually go on to play an important role in the Energiya-Buran program and later in the design of single-stage-to-orbit spaceplanes [19].