INTERCONTINENTAL CRUISE MISSILES

As the Cold War shifted into higher gear in the late 1940s, the Russians began looking at more realistic ways of delivering nuclear warheads over intercontinental distances. Unlike the US, the USSR did not have the luxury of having bases along the enemy borderline, making rockets a more convenient way of transporting nuclear bombs than strategic bombers. The leading rocket research institute was NII-88, set up in 1946. Sergey Korolyov, released from the sharaga in 1945 to study V-2 missiles in Germany, headed one of its departments. By the end of the decade NII-88 was investigating both ballistic and cruise missiles as a means of delivering nuclear bombs over long distances. In the winged arena, the emphasis now shifted from a horizontally launched piloted bomber with rocket and scramjet engines to a vertically launched unmanned two-stage cruise missile carrying rocket engines in the first stage and supersonic ramjets in a winged second stage. Unlike the ballistic missiles, the cruise missiles would remain within the boundaries of the Earth’s atmosphere, developing top speeds of around Mach 3.

A Soviet government decree issued on 4 December 1950 approved a new rocket research program, one part of which (“theme N-3’’) focused on intercontinental missiles. The conclusion of the N-3 studies was that the development of a cruise missile with a range of 8,000 km was feasible, but needed to be preceded by further

research into scramjets and navigation systems. A government decree on 13 February 1953 gave the go-ahead for the simultaneous development of both intercontinental ballistic and cruise missiles, assigning both tasks to OKB-1, which was the name given to Korolyov’s reorganized department within N11-88 in 1950. Since the cruise missile required a significant leap in technology, OKB-1 would first design an intermediate Experimental Cruise Missile (EKR). With a targeted range of 730 km, it would consist of an R-11 missile as the first stage and a winged second stage with a Bondaryuk RD-40 scramjet.

By the end of 1953 preliminary ground-based testing of EKR components had given the Russians enough confidence to skip this intermediate step and move directly to an intercontinental cruise missile with a range of 8,000 km. Since Korolyov’s OKB-1 was too heavily preoccupied with its R-7 ICBM, responsibility for the cruise missiles was entrusted to the aviation industry by a government decree released on 20 May 1954. Three aviation design bureaus were tapped to build cruise missiles with different missions:

• OKB-49 (Georgiy Beriyev): a missile called Burevestnik (“Petrel”) or “P-100” to be used for long-range reconnaissance (fulfilling the same role as the American U-2 reconnaissance aircraft) and also to deliver small 1.2-ton nuclear warheads.

• OKB-301 (Semyon Lavochkin): a missile called Burya (“Storm”) or La-350 to transport 2.18-ton atomic bombs.

• OKB-23 (Vladimir Myasishchev): a missile called Buran (“Blizzard”) or M-40 to transport 3.4-ton hydrogen bombs.

|

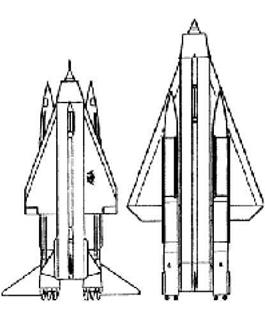

The Burya (left) and Buran cruise missiles (source: www. buran. ru) |

|

Burya lifts off (source: NPO Lavochkin). |

|

Burya in flight (source: NPO Lavochkin). |

Keldysh’s NII-1, which had once again become independent in 1952 after having been a branch of the Central Institute for Aviation Materials (TsIAM) since 1948, had overall scientific supervision of the cruise missile effort, relying on its earlier experience in high-speed and high-altitude aeronautics obtained during the antipodal bomber projects.

All cruise missiles consisted of a “core stage’’ with air-breathing scramjet engines, flanked by rocket-powered “strap-on boosters’’ (two for Burevestnik and Burya and four for Buran), giving them an appearance somewhat reminiscent of the Space Shuttle. Burevestnik seems to have been a very short-lived program that never came close to flying. Buran featured four first-stage boosters with Glushko RD-212 kerosene/nitric acid engines and a core stage with a Bondaryuk RD-018 scramjet. In August 1956 OKB-301 started work on an improved version (Buran-A or M-40A) with upgraded RD-213 engines, increasing payload capacity to 5 tons. Interestingly, Myasishchev at one point considered equipping Buran with a small crew cabin, from which the pilot was to eject prior to impact. One of the objectives of this plan was to see if a man could endure the psychological and physical rigors of hypersonic flight. Buran was scrapped in November 1957 before making its first flight.

Burya’s two strap-ons had Isayev S2.1100 rocket engines (later replaced by the S2.1150) and the core stage was powered by a Bondaryuk RD-012 scramjet. The missile underwent a series of 17 test flights from the Vladimirovka test range in the Volgograd region between September 1957 and December 1960. The maximum range achieved was 6,425 km, less than the prescribed 8,000 km, because the scramjet had a tendency of igniting too early. However, even as Burya was overcoming its teething problems, its fate had already been sealed by the successful test flights of OKB-1’s R-7 ICBM, the first of which took place in August 1957. Cruise missiles were very vulnerable to defensive measures due to their low flight altitudes (around 17-25 km) and took more than two hours to reach their targets, whereas ICBMs could deliver their deadly cargo in a matter of minutes. The US Air Force had come to the same conclusion, closing down its Navaho intercontinental cruise missile project in July 1957. The Soviet government followed suit by releasing a decree on 5 February 1960 that canceled all further work on Burya, although it allowed some of the remaining missiles to be tested in flight [12].