POST-WAR ROCKET PLANES

With turbojet development in the Soviet Union slow to take off, there was continued interest in rocket-propelled aircraft in the first post-war years, not only to counter the new threat of US strategic bombers, but also to explore the behavior of aircraft at supersonic speeds.

One project was initiated before the end of the war at NII-1, the new name given to the former NII-3 after it had merged in May 1944 with Bolkhovitinov’s OKB-293 (which also included a rocket engine department headed by Isayev). Headed by Ilya Frolov, the new effort was mainly intended to compare the performance of a pressure-fed and a turbopump-fed engine in future rocket fighters. For this purpose NII-1 developed two aerodynamically identical airplanes with straight wings: 4302 nr. 2 with a pressure-fed Isayev RD-1M engine and 4302 nr. 3 with a turbopump-fed Dushkin RD-2M-3. The RD-2M-3 was a two-chamber design with a 1,100 kg thrust main chamber and a 300 kg thrust supplementary chamber. Both chambers would be used for take-off, after which the pilot would shut down the main chamber and use the thrust of the smaller one to search for and engage the target. This technique was more fuel-efficient and allowed the plane to stay in the air longer. A glider version (4302 nr. 1) towed by a Tupolev Tu-2 made 46 flights beginning in 1946. Of the two rocket-powered versions only 4302 nr. 2 was eventually flown, making one single flight in August 1947 before funds were transferred to another rocket plane project initiated by Mikoyan.

In February 1946 the Soviet government ordered both the OKB-301 Lavochkin bureau and the OKB-155 Mikoyan bureau to develop rocket interceptors capable of reaching speeds up to Mach 0.95 and altitudes of up to 18 km. Both planes were to be equipped with modified Dushkin RD-2M-3V dual-chamber engines. Lavochkin’s team studied a plane with a radar sight called La-162, but abandoned work on it in late 1946, preferring to fully concentrate their efforts on jet aircraft. The Mikoyan version was called I-270 and was heavily influenced by the German Me-263-V1 rocket fighter, which had been captured by the Red Army and carted off to the Soviet Union. The Me-263-V1 was one in a long line of Messerschmitt rocket fighters, one of which (the “Komet”) had been the only rocket fighter ever to be used in combat. Although the I-270 featured a similar cockpit and landing gear arrangement, it was substantially longer than the Me-263 and also had mid-mounted straight wings and a tee tail rather than the swept wings and tailless design of the German interceptor.

Two experimental I-270 planes were built, one designated Zh-1 and the other Zh-2. Towed by a Tu-2 bomber, Zh-1 made 11 unpowered test flights between February and June 1947. Zh-2 performed the first rocket-propelled flight in September 1947, but was irreparably damaged when it landed far off the runway. Zh-1 also suffered damage on its first powered flight in October 1947 when the landing gear

failed to deploy, but was repaired for one final flight in May 1948. The test flights were rather conservative, with the planes developing speeds of only about 600 km/h.

In the second half of 1945 the design bureau of Pavel V. Tsybin was tasked with studying various wing configurations for use at near supersonic speeds. For this purpose the bureau developed “Flying Laboratories” (LL) powered by a Kartukhov PRD-1500 solid rocket motor. Two configurations were tested: LL-1 (or Ts-1) with straight wings and LL-3 (or Ts-3) with 30° forward-swept wings. The LL-1 and LL-3 made about 130 flights in 1947-1948, with the latter reaching speeds of up to Mach 0.97. A planned LL-2 with 30° swept-back wings was not flown because that wing configuration had already been tested on the MiG-15 and La-15 fighters.

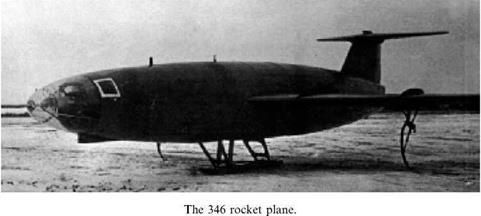

Meanwhile, the Soviets were also out to break the sound barrier with rocket – propelled airplanes, relying both on a captured German and a derived domestic design. The German rocket plane was the 346, originally developed by the German Institute for Sailplane Flight (DFS) in 1944. After shutting down its engine, the plane was supposed to glide over enemy territory to take reconnaissance photos and then re-ignite the engine to gain enough speed and altitude to glide back to a friendly base in France or Germany. It had a long, slender fuselage reminiscent of a rocket, with 45° swept-back wings. Thrust was to be provided by a dual-chamber HWK 109-509C. The pilot was supposed to lie in a prone position. In case of an emergency the cabin could be separated from the airplane, with the pilot subsequently ejecting for a parachute landing.

Having fallen into Soviet hands at the end of the war, the German team that had been working on the 346 was sent to Podberyozye (some 100 km north of Moscow) in October 1946 to continue development of the rocket plane under the leadership of Hans Rossing in a newly created Soviet-German design bureau called OKB-2. In the second half of 1948 Rossing’s team completed work on a glider version of the plane called 346-P, which was flown several times by German test pilot Wolfgang Ziese in 1948-1949. The carrier aircraft for these and subsequent test flights was an American B-29 bomber confiscated by the Russians after having made an emergency landing in Vladivostok in 1944. In 1949 Ziese and Soviet pilot Pyotr Kazmin were behind the controls for three drop tests of a version of the 346 carrying a mock-up rocket engine (346-1). Despite landing problems on all three flights, the team pressed ahead with the development of the first rocket-propelled model called 346-3.

Ziese performed three powered flights in August-September 1951. During the third flight he lost control of the plane after engine shutdown, forcing him to separate the cabin and eject. With only one of the two combustion chambers activated during these test flights, the maximum speed reached was just over 900 km/h. The 346 could have broken the sound barrier with both chambers working, but OKB-2 was reportedly wary of making such an attempt because of aerodynamic insufficiencies in the airplane. Plans for a delta-wing supersonic rocket plane called 486 were scrapped and the German team was eventually repatriated to the GDR in 1953.

Concurrently with the Germans at Podberyozye, a team under Matus Bisnovat worked on an indigenous supersonic rocket plane called Samolyot-5 (“Airplane-5”). Bisnovat had been placed in charge of the OKB-293 design bureau in June 1946,

|

|

when it separated from NII-1 to once again become an independent entity. With its 45° swept-back wings, Samolyot 5 was outwardly very similar to the 346, also featuring a jettisonable cabin. It would use a twin-chamber Dushkin RD-2M-3F with a total thrust of 1,600 kg to reach speeds of up to Mach 1.1.

Bisnovat’s team initially developed a scale model called “Model 6” that was dropped on four occasions from a Tu-2 bomber between September and November 1947. Claims that speeds of Mach 1.28 and Mach 1.11 were attained on the two final flights are hard to verify because the speedometers were not retrieved intact. With the Dushkin engine not yet ready, a glider version designated 5-1 performed three drop tests from a Pe-8 bomber between July and September 1948, but it was damaged beyond repair in a landing accident on the final mission. Eight or nine more drop tests were conducted with airplane 5-2 between January and June 1949, but that same year financing for Samolyot-5 was discontinued even though the Dushkin engine had been test-fired and installed on the 5-2 [9].

By the end of the 1940s the era of the rocket planes was drawing to a close. Because of their limited flight times, they had little military value, among other things because the pilot had a hard time gliding back to a safe landing. Another safety issue was the use of toxic nitric acid in all the rocket engines developed for the Soviet rocket planes. A much cheaper, safer, and more efficient way of shooting down enemy bombers was the use of surface-to-air missiles, something that the Russians realized shortly after the end of the war when they stumbled on advanced German SAM missiles such as the Wasserfall.

After the war, rocket engines were a handy way of testing aircraft performance at supersonic speeds, but their development was gradually being overtaken by that of the jet engine, even though the Russians mainly relied on copies of German and British engines. While Chuck Yeager had become the first man to break the sound barrier on the X-1 rocket plane on 14 October 1947, the Russians achieved the same feat a year later, but not on one of their rocket-propelled aircraft. On 26 December 1948 Oleg Sokolovskiy became the first Soviet pilot to exceed Mach 1, flying a

|

The Samolyot 5 rocket plane. |

Lavochkin La-176 jet plane. Despite the simultaneous development of the 346 and Samolyot-5, no Russian pilot ever flew faster than the speed of sound on a rocket – propelled aircraft. In the first half of 1950 a special commission set up under the Ministry of the Aviation Industry concluded that rocket engines had little future in aviation and a government decree in June 1950 closed down all further work on rocket engines for aircraft at NII-1.