Short-range interceptors

The only Soviet short-range interceptor that ever made powered flights during the war was the BI (for blizhniy istrebitel or “short-range fighter’’), developed at the OKB-293 design bureau of Viktor Bolkhovitinov under the leadership of Aleksandr Bereznyak and Aleksey Isayev. It had a fabric-skinned wooden frame, low-mounted straight wings, a “razorback’’ style canopy and twin 20mm cannons mounted in front of the canopy. Installed in the aft was a D-1A-1100 nitric acid/kerosene engine developed by Dushkin at NII-3 capable of throttling between 400 kg and 1,100 kg. The originally planned turbopump was replaced by a pressure-fed system designed by Isayev. With a maximum propellant load of 705 kg, the engine could burn for almost two minutes. Maximum take-off mass was 1,650 kg (dry mass 805 kg).

Work on the BI began in late 1940, but was not given priority until after the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. In July Stalin ordered the OKB-293 team to build the first BI in just 35 days instead of the three to four months that Bereznyak and Isayev had planned. Amazingly, the first BI was duly delivered in mid-September and in the following weeks made 15 unpowered flights, towed by a Pe-2 bomber. In October 1941, with German troops approaching Moscow, Bolkhovitinov’s design bureau was evacuated to the Urals near Sverdlovsk, where the BI-1 tests continued with a series of static test firings and take-off runs. The first

|

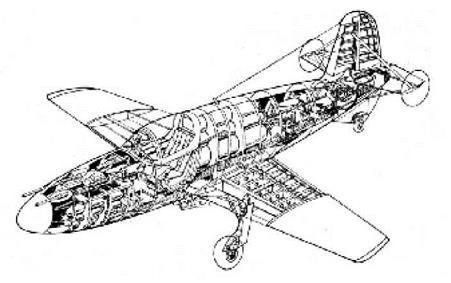

Cutaway drawing of the BI rocket plane. |

powered flight took place on 15 May 1942 with Grigoriy Bakhchivandzhi behind the controls. The D-1A-1100 boosted the BI-1 to an altitude of 840 m and a maximum speed of 400 km/h. Just over three minutes after take-off, the BI-1 made a hard landing, seriously damaging its landing gear.

The next test flights were performed with the BI-2 and BI-3, which only differed from the first aircraft in having a skid landing gear. The BI-2 made four flights in January-March 1943 (three by Bakhchivandzhi and one by Konstantin Gruzdev), pushing the maximum speed and altitude to 675 km/h and 4 km, respectively. Bakhchivandzhi was again at the helm for flights 6 and 7 on the BI-3. Unfortunately, the seventh flight on 27 March 1943 ended in tragedy, when the BI-3 went into a dive shortly after engine shutdown and crashed, killing its pilot. The accident had a stifling effect on the rocket plane program, the more so because the cause was never clearly established. Plans for building a batch of 50 production planes (BI-VS) equipped with small bombs were canceled. However, more experimental planes were built with the goal of increasing the very limited flight duration, which was seen as one of the main disadvantages of the plane. One BI version was fitted with two wing-mounted ramjet engines and another one with an improved 1,100 kg thrust engine developed by Isayev (the RD-1). Both made test flights in 1944 and 1945.

NII-3, now headed by Andrey Kostikov, did not only provide the engine for the BI, but also worked on its own short-range interceptor. Originally, the institute had hoped to build upon the success of the RP-381-1 by equipping the plane with an improved 300 kg thrust RD-1-300 engine that would have allowed it to take off on its own power. Also studied was a rocket plane based on the G-14 glider with a liquid oxygen/ethanol RDK-1-150 engine developed by Dushkin. However, in 1940 those plans were abandoned in favor of a short-range interceptor called “302”, which would have a liquid-fuel rocket engine mounted in the rear fuselage and two ramjets under the wings to increase flight duration, giving it an advantage over the BI. The rocket engine was Dushkin’s RD-1400 (later renamed RD-2M), capable of throttling between 1,100 and 1,400 kg.

Work was temporarily suspended after the German invasion in June 1941, when NII-3 concentrated all its efforts on the famous Katyusha missiles. However, in 1942 Stalin ordered work to be resumed, with aircraft designer Matus Bisnovat joining the team in early 1943. A glider version called 302P was flown several times in late 1943 (towed by Tu-2 and B-25 aircraft) and was piloted among others by the later cosmonaut candidate Sergey Anokhin. Unfortunately, development problems with both the rocket and ramjet engines, the availability of the BI fighters, and the decreasing interest in rocket-propelled interceptors eventually led to the cancellation of the project in early 1944. Kostikov, who had reportedly denounced both Glushko and Korolyov in 1938, was now arrested himself for having made unauthorized changes to the test program, but was rehabilitated in February 1945.

There were also several interceptor proposals that never went beyond the drawing board. In 1942 the Yakovlev design bureau finished the design of a rocket plane based on its YaK-7 aircraft. Called the YaK-7R, it would carry a single Dushkin D-1-A-1100 rocket engine in the tail and two Merkulov DM-4S ramjets under the wings. However, the project stalled due to development problems with the ramjets. In late 1943 the OKB-51 design bureau of Nikolay Polikarpov began work on a rocket plane called Malyutka (“Baby”) using an unidentified rocket engine with a thrust of between 1,000 and 1,200 kg. Malyutka was expected to develop a speed of 845 km/h and reach a maximum altitude of 16 km during an 8 to 14 minute flight. The project was canceled after Polikarpov’s death in July 1944.

Other proposals were based on the use of a 1,200 kg thrust, four-chamber nitric acid/kerosene engine designed by Valentin Glushko. Equipped with a turbopump, it was called RD-1, not to be confused with its namesake developed by Isayev for the BI. Still a prisoner, Glushko was working at the time for the 28th Special Department of the NKVD secret police in the city of Kazan. This was a so-called sharaga, a type of penitentiary for scientists and engineers to work on projects assigned by the Communist Party.

One man displaying interest in the engine was Roberto Bartini, an Italian-born aircraft designer who as a member of the Italian Communist Party was transferred undercover to the USSR in 1923 after the Fascist revolution. Arrested in 1937 because of his ties to Tukhachevskiy, Bartini ended up in the 29th Central Design Bureau (TsKB-29) of the NKVD in Omsk, a sharaga that served as the engineering facility for Andrey Tupolev. During 1941-1942 he drew up plans for a rocket plane with swept-back wings called R-114 that would use the RD-1 to reach phenomenal speeds of over 2,000 km/h.

Glushko’s RD-1 also figured prominently in rocket plane proposals by Sergey Korolyov, who, after having barely survived the hardships of the Kolyma gulag camps in far eastern Siberia, had been sent back west in 1940 to work under Tupolev at TsKB-29 (first in Moscow, then in Omsk) and was subsequently transferred to Glushko’s sharaga in Kazan in November 1942. The following month he finished plans for two rocket planes, one weighing 2,150 kg and the other 2,500 kg, with Korolyov preferring the latter version. Equipped with the four-chamber RD-1, the plane would be able to intercept any enemy aircraft at any altitude and even be capable of attacking ground-based targets such as tanks, artillery batteries, and surface-to-air missile installations. It would outperform the BI in every respect, staying in the air for 10.5 minutes (vs. 2 minutes for the BI) at a speed of 800 km/ h and carrying 200 kg of weaponry (vs. 50-100 kg for the BI-1). Korolyov also suggested mounting an RD-1 type engine on a 3,500 kg “flying wing” type interceptor that would be able to stay in the air for 30 minutes and reach a maximum altitude of 15 km. A similar flying wing (“RM-1”) with a Dushkin RD-2M-3V engine was studied by the OKB-31 design bureau of Aleksandr Moskalyov in 1945-1946.

Advanced as both Bartini’s and Korolyov’s proposals may have been, they had little resonance. Put forward by men who officially were still “enemies of the people’’, they stood little chance against official, government-supported projects such as the BI and “302” [7].