ALONG THE RILLE OF LE MONNIER BAY

Apollo ended in December 1972, and from thereon the Russians knew that they had the moon to themselves. When Luna 21 headed moonwards on 8th January 1973, the launching was seen in the West as deliberately calculated to take advantage of the end of the Apollo programme. In fact, the timing was coincidental. The second mooncar, for that was what Luna 21 carried, had taken a full year to redesign after Lunokhod had terminated its programme. Luna 21 weighed 1,814 kg and its translunar flight was problematical. False telemetry signals nearly aborted the mission and then Lunokhod 2’s solar lid opened during the translunar coast, without being asked to do so.

|

Luna 20 landed in snow |

|

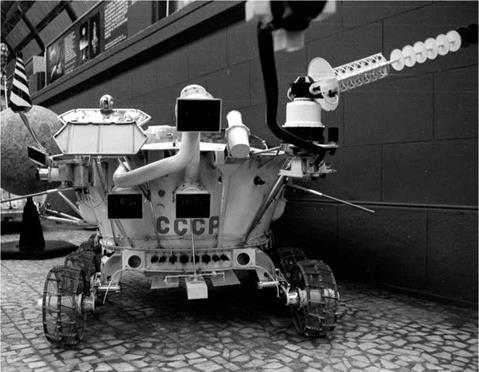

Lunokhod 2 |

Luna 21 entered a near-circular lunar orbit on schedule on 12th January between 90 km and 110 km, 1 hr 58 min, 60°. The next day, the perilune was lowered to 16 km. On its 41st moon orbit, 255 km from its objective, Luna 21 began its descent from an altitude of 16 km, coming down at 215m/sec. The target was the 55 km wide Le Monnier cratered bay, the target for the first, failed Lunokhod in 1969. Le Monnier was only 180 km from the valley just visited by Jack Schmitt and Eugene Cernan of Apollo 17. Off the edge of the Sea of Serenity, the now eroded remains of the Le Monnier crater cut into the edge of the rocky Taurus Mountains. The main engine blasted at 750 m, cutting out at 22 m when a secondary thruster brought the spacecraft down to 1.5 m, from which height it fell gently to the surface at 7km/hr.

Luna 21 came down in a relatively flat area surrounded by the high rims of the old crater. The site had been chosen because Le Monnier marked the transition between the low mare and the upland continental area. Le Monnier was a flooded rim rather than a sharply defined crater. The location was 25.85°N, 30.45°E, the landing time 02: 35 Moscow time on 16th January. The navigation system failed at the moment of touchdown, which meant that – although the rover was intact – the drivers were not sure exactly where it was.

Lunokhod 2 first activated its cameras and panned around the landing site from the high vantage point of the landing state. With the slogan Fifty years of the Soviet

|

Lunokhod 2 with hills behind |

Union! 1923-1973 emblazoned on it, Lunokhod 2 rolled down the landing ramps not long afterwards. Lunokhod 2 at once made a trial journey over the surface and then parked for two days 30 m away to charge up the batteries. Cameras at once showed the mare, the crater rim to the south and a massive stone split into lumps in the foreground.

Lunokhod 2 was a distinct improvement over its predecessor. It was 100 kg heavier at 840 kg. It could travel at twice the speed, having two speeds, 1 km/hr and 2 km/hr (its average turned out to be 15.5 m/hr). Lunokhod 2 was designed to handle obstacles of 40 cm and holes of 60 cm. It had twice the range. Addressing some of the driving problems arising from the first Lunokhod, pictures were now transmitted to its drivers every 3.2 sec, compared with 20 sec before. The cameras were moved much higher. Lunokhod 2 had three low-rate cameras on the front, able to scan 360° vertically and 30° horizontally, with two double panoramic cameras able to scan 180° horizontally and 30° vertically. The television cameras had three possible scan rates: 3.2, 5.7 and 21.1 sec per frame. There were new scientific instruments, most notably a photodetector called Rubin to detect ultraviolet light sources in our galaxy and the level of Earthglow on the nighttime moon. The heat source was again an isotope made of polonium-210. The magnetometer was deployed on a boom 2.5 m in front. The laser reflector had an accuracy of 25 cm.

Lunokhod 2’s programme was first to inspect the descent stage, to which it would not return and then it would head south to the mountains 7 km away and explore there. In its first journeys, Lunokhod 2 investigated craters close to the landing stage, taking detours to avoid big rocks. At the end of its first lunar day, Lunokhod 2 parked 1 km southeast from its landing stage.

Lunokhod 2 instruments

• Soil mechanics tester.

• Solar X-ray detector.

• Magnetometer.

• Photodetector (Rubin).

• Laser reflector (France).

|

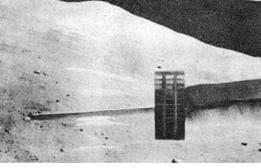

Lunokhod 2 wheel marks on the moon |

On 8th February, Lunokhod 2 began its first full lunar day and in ten days reached the southern rim of Le Monnier, exploring the edge of the rim and two craters there, one 2 km wide. The nature of the ground varied from soft and loose to hard and firm. In one crater in the foothills, it circled around the edge of a crater with a 25° slope, taking analyses at numerous spots. In the course of one of its early sessions, the bug-eyed roving vehicle went 1,148 m in six hours – much faster than anything achieved before. It climbed one hill of 400 m, with its wheels at one stage slipping up to 80%. From the top it sent back an eerie photograph of the Taurus peaks glowing to the north, 60 km away and the thin sickle of the Earth rising just above. As it journeyed, it measured and analyzed the lunar soil. Lunokhod 2 rambled around the southern rim of Le Monnier. By the end of February, the rover had travelled farther than the first Lunokhod in its ten months.

Now, in March, Lunokhod 2 headed off on its greatest adventure. On the day the Lunokhod landed, the Institute of Space Research (IKI) in Moscow was holding a symposium on solar system exploration, one also attended by American scientists. One of the Americans had brought with with him a batch of new Apollo 17 pictures of that region of the moon, for it was close to the Apollo 17 landing site, giving them to Lavochkin lunar bureau chief Oleg Ivanovsky. They were so detailed that they showed up a new rille, 16 km long and 300m wide, the Fossa Recta, to the east of the rover. Lunokhod 2 was duly directed there, setting out on an eastward course to explore the new rille and there it travelled, the flat crater of Le Monnier on its left flank, its rim and the Taurus Mountains on its right. The rover skirted around small craters as it journeyed eastward. By 20th March it was just west of the rille.

On lunar day 4, April, Lunokhod 2 travelled southwest around the southern end of the rille, exploring it from both sides. Here, geologists were excited to spot an outcrop of bedrock. Although the surface was a firm volcanic basalt, there were occasional dusty soft spots and at one stage the tracks of the rover sank about 20 cm into the lunar surface. The journey along the rille was a dangerous one, for there were many metre-size boulders along its ledge. Lunokhod parked around the eastern side on 19th April. The magnetometer identified a magnetic anomaly on the western edge of the rille.

The ground control veterans of Lunokhod, temporarily idle for a year, had resumed their work in two shifts of two hours each. Driving the Lunokhod over the moon required teamwork. The navigator was responsible for the route over the

|

Driving the Lunokhod |

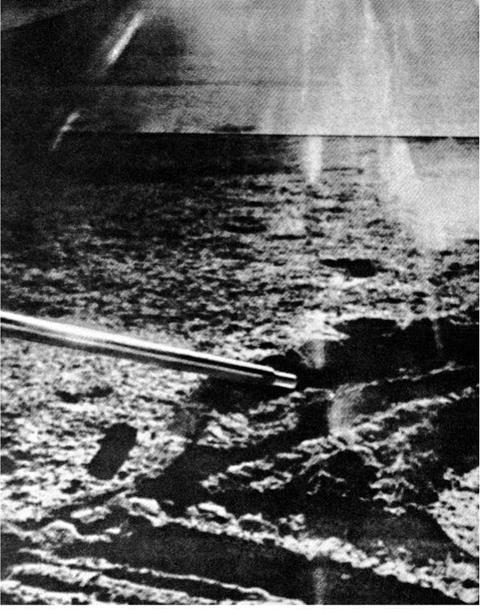

Foothills at crater rim

Foothills at crater rim

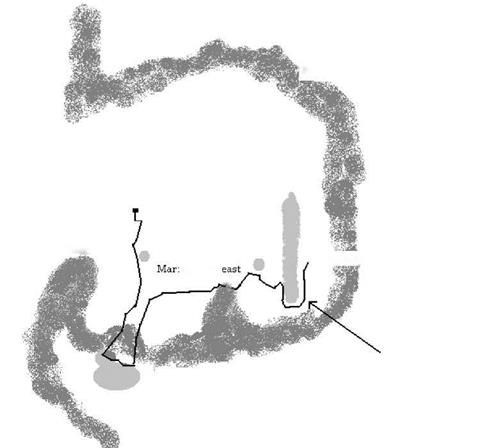

The journey of Lunokhod 2

lunar surface, but in reality the decisions were taken by the whole team, once even voting on the best route. The radio and antenna operator was responsible for ensuring that – whatever the direction of the rover – the antenna was pointing toward Earth and the solar lid was in a position to collect sufficient energy from the sun. The teams worked their shifts according to the lunar day and night and sometimes lost track of Earth time, day and night. Once, during an especially tense drive across the moon, contact with Lunokhod broke off abruptly. Only when they pulled back the curtains of the control room did that realize that the reason was that the moon had just set below the horizon.

In May, Lunokhod resumed its journey on the eastern side of the rille, once traversing up an 18° slope. It was expected that Lunokhod 2 would continue its work for several months, but on 4th June came the sudden announcement from Radio Moscow that ‘the programme had been completed.’ No explanation was given at the time, nor a suggestion that anything had gone amiss. Like so many events in the Soviet

lunar programme, the real story did not emerge for ages – 30 years later [10]. Some extreme versions even came out, like that the moon rover had ‘turned turtle’.

The reality was more prosaic. On 9th May, soon into the new lunar day, Lunokhod had descended into a small but deep 5 m wide crater inside a much larger crater, its depth concealed by the shadows thrown by a low-sun angle. As the drivers tried to manoeuvre Lunokhod out of the crater, the lid touched the crater wall, dumping clumps of lunar soil onto the solar cells. The immediate consequences were not serious – the loss of some electric power – but the long-term consequences were fatal. When night came, the lid was closed, as normal. In closing the lid, the soil was then dumped onto the radiator. When lunar dawn came in early June and the lid was raised again, the lunar soil acted as an insulator, preventing the rover from properly releasing its heat. The heat inside rose and Lunokhod quickly died.

The Russians seem to have been disappointed, but there is little reason why they should have been. Lunokhod 2 had travelled 37 km, sent back 86 panoramic pictures and 80,000 television pictures and had covered four times the area of its predecessor. It had investigated not only crater floors but much more difficult geological features like rilles and uplands. One of its most interesting findings actually had nothing to do with the lunar surface, but the suitability of the moon as a base for observing the sky. Whilst it would be excellent during the lunar night, during the daytime the lunar sky was surrounded by a swarm of dust particles, a kind of atmosphere that would make telescopic observations very difficult. The astrophotometer determined that the lunar night sky was, in Earthglow, 15 times brighter than Earth’s night sky in moonlight. Detailed tables of the composition of the lunar rocks were published, comparing those sampled by Luna 16, Lunokhod 1 and Lunokhod 2. In the case of Lunokhod 2, it was possible to make comparisons between the composition of the mare and continental rocks [11], the proportions of aluminium, silicon, potassium and iron being different. The RIFMA-M X-ray flourescent spectrometer measured the soil near the lander as 24% silicon, 8% calcium, 6% iron and 9% aluminium, but the soil at the edge of the Taurus Hills showed a sharp rise in iron content. Lunokhod 2’s average speed was 27.9 m/hr, seven times faster than its predecessor and it covered seven times the distance. Up to a thousand penetrations of the lunar surface were made by the two rovers between them. The laser fired 4,000 times with an accuracy of 25 cm. The magnetometer had been installed following measurements of some form of lunar ionosphere by Luna 19 the previous year. Lunokhod 2’s magnetometer determined

|

Table 7.3. The journey of Lunokhod 2, 1973

|

that there was a very weak permanent magnetic field around the moon, its measurements being broadly in line with those of Apollo. The temperature of the lunar night was measured at — 183°C. Back in Moscow, mission scientists made a geological map of Le Monnier Bay, complete with slices of the surface, bedrock and underlying strata.