‘LUNOKHOD, NOT LUNOSTOP’

Scientists sat in an adjoining room watching the pictures and hearing the comments of the drivers, but were not allowed into the control room. This was quite different from American practice for, when American rovers explored Mars in 1997 (Sojourner) and 2004 (Spirit and Opportunity), the scientists were an integral part of the team. Eventually and Babakin’s edict notwithstanding, the principal lunar geologist, Alexander Basilevsky of the Vernadsky Institute for Geochemistry, could bear the separation no longer, brought his chair into the control room and watched quietly from close quarters. There was quite a contrast between the way the Russians approached things on the moon and the way the Americans subsequently did on Mars. Whenever Basilevsky wanted to examine a rock, the drivers wanted to avoid it, for fear of collision or getting stuck – by contrast, the American Mars rovers spent extensive periods getting up close and personal to individual interesting rocks. Georgi Babakin, aware of thirst in Pravda for ‘how many kilometres did we do today?’ once told Basilevsky gently that this was a Lunokhod, not a Lunostop.

As time went on, it became apparent that Lunokhod was not just a playful bathtub on wheels but a sophisticated machine with advanced instrumentation. The soil analyzer RIFMA bombarded the surface with X-rays and enabled ground control to read back the chemical composition of the basalt-type soil. From time to time, the PrOP mechanical rod jabbed into the soil to test its strength. When it did so, it was able to measure resistance. Then, it was turned in the soil, this time to measure turning resistance. Once done, it was retracted and the vehicle moved on. Lunokhod did not only look moonwards: there were two telescopes on board – one to pick up X-rays beyond the galaxy and another to receive cosmic radiation. On 19th Novem-

|

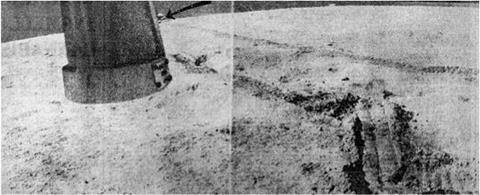

Lunokhod tracks from landing stage |

|

Lunokhod porthole view |

ber, Lunokhod recorded a strong solar flare that could have injured cosmonauts had they been on the moon at the time. Lunokhod therefore contained within it several concepts: an exploring roving vehicle; a rock-testing mobile laboratory; and an observatory able to capitalize on the unique air-free low-gravity environment beyond the Earth. The rocks were abundant in aluminium, calcium, silicon, iron, magnesium and titanium. The Sea of Rains had been selected because it was a typical mare area.

Come the new year, 1971, Lunokhod was back in action once more, heading back north to its landing site, whence it returned in mid-January. A spectacular photograph of the landing vehicle with ramps and wheel tracks all about reminded the world that Lunokhod was still there, prowling about the waterless sea of the Bay of Rains. The normal procedure was to lift the solar lid when the sun was 5° over the horizon. The first thing Lunokhod would do was radio back its condition (for the record: internal temperature 22°, pressure 753 mm (May)). Now Lunokhod headed north on a much longer journey from which it would not return. By the fourth lunar day, 8th February, scientists were able to compile a map of that part of the Bay of Rains adjacent to Luna 17. On 9th February, the mooncar survived a lunar eclipse when temperatures plunged from +150°C to —100°C and back to +136°C, all in the space of three hours. In March, Lunokhod explored around the rim of a 500 m wide large crater, venturing into smaller craters within the rim of the larger circle.

In April, Lunokhod ventured to a crater field full of boulders over 3 m across. Because of a nearby crater impact, all the black lunar dust had piled up against one side of the boulders as if a hurricane had swept through. Eventually, the geologists persuaded the control room supervisor to concentrate more on science and photographing features of interest and less, as they saw it, on building up distance records for the pages of Pravda. Drivers wanted to avoid rocks that might endanger Lunokhod, but the scientists wanted to examine them at close quarters. On 13th April, Lunokhod became badly stuck in loose soil on a crater slope, but by applying full power on all engines it emerged out onto more solid, level ground. This nearly exhausted the system and the rover was parked for the rest of the month, simply

|

recharging. Lunokhod travelled only 197 m in May, concentrating on static experiments. The mooncar had appeared to be losing power and it was probably decided to concentrate on less energy-demanding experiments (Lunokhod was never expected to last more than six months).

Measurement of the strength of the lunar surface was an important aspect of the work of Lunokhod. The vehicle would stop and the penetrating cone would be lowered at the back of the vehicle. The penetrator, called PrOP, coned at an angle of 60°. First, it was forced into the surface to a depth of up to 5 cm to test force. Some pressure was applied, equivalent to a sixth of the weight of the rover. Then vanes inside the cone were rotated 90° for torque, again another measurement of surface strength. This was done 500 times. The results of penetration and trafficability tests were published in detail, finding that Lunokhod operated on surfaces that were

much weaker than the lunar roving vehicles driven by the Apollo 15-17 astronauts. In September, penetrometer stops were made every 65 m.

Whatever the power problems might have been, they lifted – for in June Lunokhod headed 1,559 m north-northeast to a further set of four craters, which were set to be its final exploration area. It explored this area thoroughly, and it would seem that Lunokhod’s power was really beginning to fail at this time. Total distances travelled were falling: 220 m in July, 215 m in August and only 88 m in September. Earlier, on 5th August, American astronauts David Scott, James Irwin and Al Worden flew directly over the mooncar in their Apollo 15 command module and Lunokhod’s magnesium alloy frame glinted in the Sun. As it drove slowly, plodding across the moonscape, the two different moon explorers stood in stark contrast to one other.

Then, suddenly, whilst at work on 4th October exploring a group of four craters far north of the landing site, Lunokhod’s ‘heart’ – its isotope power source – gave out. Telemetry reported a rapid drop in pressure inside the hermetically sealed cabin. The wheels halted, the TV pictures and signals ceased. It was the end.

Considering Lunokhod had been designed to function for only three months and had worked for nearly a year, its mission was a cause of much congratulation. It was the USSR’s most brilliant achievement in the field of automatic space exploration. Apparently primitive in design, superbly built, with a reliability the perfectionist buffs in NASA would have envied, it endeared itself to the public at large and became the most exciting robot of its day. In statistical terms alone, its achievement was impressive. It had travelled 10.54 km, covered an area of 80,000 m2, sent back 20,000 pictures including 200 panoramas and X-rayed the soil at 25 locations. Only later did the Russians reveal that in fact the braking system on Lunokhod had failed quite early in the ‘on’ position and all the time it was driving against the friction of its brakes. The driving team and the scientists were exhausted. For ten months, they had worked

|

Table 7.2. The journey of Lunokhod, 1970-1

|

ten-hour shifts, 14 lunar days at a time, punctuated by short breaks for the three days of lunar noon when they would enjoy the nearby seaside resort and longer 14-day breaks for the lunar night, when they flew back to Moscow to review their data.