WINDING DOWN THE L-l ZOND AROUND-THE-MOON PROGRAMME

Even though Apollo 8 had flown around the moon in December 1968, the L-1 programme was not abandoned. There were several reasons. The hardware had been built or was still in construction. So much investment had gone into the programme that it was felt better to test out the technical concepts involved than write them off altogether and deny oneself the benefits of the design work. If these tests went well, a manned moon circumlunar mission could still be kept open as an option. Indeed, with some of the political pressure lifted, designers looked forward to testing their equipment without the enforced haste required by American deadlines. There was also an official problem, bizarre to outsiders, which was that the Soviet government lacked a mechanism to stop the moon programme. At governmental level, no one was yet prepared to admit failure or to take responsibility for what had gone wrong [10]. The resolutions of August 1964 and February 1967 remained in effect, unrepealed. According to Alexei Leonov, the government decided that if the next Zond succeeded, then the following one would be a manned flight, even after Apollo 8.

A new Zond was readied in January and left the pad on 20th January 1969. It is unclear what profile it would have flown, for it was outside the normal launch window. The cabin used was the one salvaged from the April 1968 failure [11]. The second stage shut down 25 sec early at 313 sec, but the other second-stage engines completed the burn. During third-stage firing, the fuel pipeline broke down and the main engine switched off at 500 sec, triggering a full abort. The emergency system lifted the Zond cabin to safety, and it was later retrieved from a deep valley near the Mongolian border. As we know, the period January to July 1969 lacked good launch-and-return windows for Zond missions around the moon, so any missions would have to be performed either under less than ideal tracking, transit or lighting conditions, or would have to be fired at a simulated moon, which was probably the case this time.

There were still Zond spacecraft available. At this stage, a perfect circumlunar flight was still required before a manned mission could be contemplated. However, a Russian manned circumlunar flight would now, after Apollo 11, make an even more

|

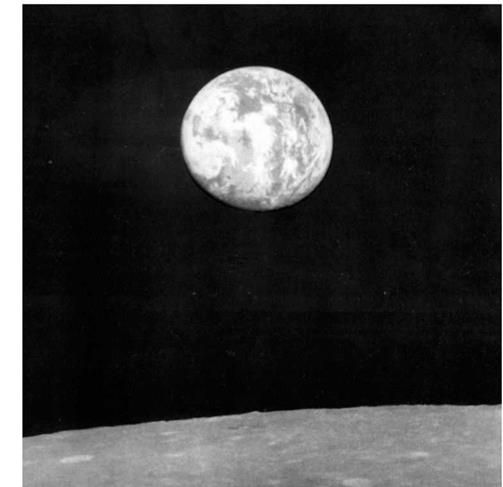

A full Earth for Zond 7 |

invidious comparison after Apollo 8. The chances that the cosmonauts would be allowed to fly were fading.

The Russians took advantage of the first of the new series of lunar opportunities opening in the autumn. Zond 7 left Baikonour on 8th August 1969, only two weeks after Luna 15’s demise and at about the time that the Apollo 11 astronauts were emerging from their biological isolation after their moon flight. Thirty turtles had been ready for the mission and four were selected. Zond 7 was the only one of the series to carry colour cameras. Cameras whirred as Zond skimmed past the Ocean of Storms and swung round the western lunar farside 2,000 km over the Leibnitz Mountains. Zond 7 carried a different camera from its predecessors, a 300 mm camera with colour film taking 5.6 cm2 images. Strikingly beautiful colour pictures were taken

of the Earth’s full globe over the moon’s surface as Zond came around the back of the moon. Like Zond 5, voice transmissions were sent on the way back. Zond 7 headed back to the Earth, skipped like a pebble across the atmosphere to soft land in the summer fields of Kustanai in Kazakhstan after 138 hr 25 min. It was a textbook mission.

How easy it all seemed now. After the total success of Zond 7, plans for a manned circumlunar mission were revived and there were still four more Zond spacecraft in the construction shop – one even turned up in subsequent pictures with ‘Zond 9’ painted in red on the side. The state commission responsible for the L-1 Zond programme met on 19th September and the decision was taken to fly Zond 8 as a final rehearsal around the moon in December 1969, with a manned mission to mark the centenary of Lenin’s birth in April 1970, which would be a big national event.

This plan, which was probably designed to appeal to the political leadership, did not in fact win government approval. There were mixed opinions among those administering the Soviet space programme as to whether a man-around-the-moon programme should still fly. Many had serious reservations about flying a mission that would be visibly far inferior not only to Apollo 11 but to the two Apollo lunar – orbiting flights that preceded it. Others disagreed, arguing that the Soviet Union would, by sending cosmonauts to the moon and back, demonstrate at least some form of parity with the United States. In 1970, few other manned spaceflights were in prospect, so a flight around the moon would at least boost morale. The normally cautious chief designer Vasili Mishin pressed hard for cosmonauts to make the lunar journey on the basis that the experience gained would be important in paving the way for a manned journey to a landing later. The political decision, though, was a final ‘no’, the compromise being that Mishin was allowed to fly one more Zond but without a crew. Two of the cosmonauts in the programme subsequently went on record to explain the decision. The political bosses were afraid of the risk that someone would be killed, said Oleg Makarov, who was slated for the mission. Another cosmonaut involved, Georgi Grechko, felt that the primary reason was political: there was no point in doing something the Americans had already done [12]. In the end, Lenin’s centenary was marked, indirectly and two months after the event, by the 18-day duration mission of Andrian Nikolayev and Vitally Sevastianov.

Zond 8 was eventually flown (20th-27th October 1970). It carried tortoises, flies, onions, wheat, barley and microbes and was the subject of new navigation tests. Astronomical telescopes photographed Zond as far as 300,000 km out from Earth to check its trajectory. Zond 8 came as close as 1,110 km over the northern hemisphere of the lunar surface, the closest of all the Zonds. Two sets of black-and-white images were taken, before and after approach. The 400 mm black-and-white camera of the type used on Zonds 5 and 6 was carried. These were high-density pictures, 8,000 by 6,000 pixels and are still some of the best close-up pictures of the moon ever taken [13].

There have been contradictory views as to whether Zond 8 was intended to return to the Soviet Union or be recovered in the Indian Ocean. The records now show that the recovery in the Indian Ocean was deliberate and not the result of a failure. As we know, the optimum trajectory for a returning Zond was to reenter over the southern hemisphere and make a skip reentry, coming down in the normal land recovery zone (Zond 6 and 7), or, if the skip failed, a ballistic descent into the Indian Ocean (Zond 5).

The alternative approach, one favoured by Mishin, was to come through reentry over the northern hemisphere, with good contact with the ground during this crucial period, but make a southern hemisphere splashdown. This route had not been tried before. Two Soviet writers of the period confirm that the purpose of Zond 8 was indeed ‘to make it possible to verify another landing version with deceleration over the USSR’ [14]. Zond 8 made a smooth northern hemisphere skip reentry and came down in the Indian Ocean 24 km from its pinpoint target where it was found within 15 min by the ship Taman. This seemed to prove Mishin’s point. Six years later, though, cosmonauts Vyacheslav Zudov and Valeri Rozhdestvensky splashed down in a lake and very nearly drowned during a protracted and hazardous recovery.

Analysis of the biological samples found similar results across the series. The turtles were hungry and thirsty after their return: hardly a surprise as they had not been fed or watered during their mission. They were examined for changes to their heart, vital organs and blood. There were some mutations in the seeds as a result of radiation. Overall, radiation dosages seemed to be well within acceptable limits, not posting a danger to cosmonauts and not significantly different from conditions in Earth orbit.

Thus, of nine Zond missions and of six attempts to fly to the moon, only Zond 7 and 8 were wholly successful. The last two production Zonds were never used. Just as the Russians tested their lunar hardware in Earth orbit successfully (Cosmos 379, 382, 398,434), they tested their round-the-moon hardware successfully. We now know that the Russians reached the stage where they could, with a reasonable prospect of success, have proceeded to a manned around-the-moon flight. Years later, Vasili Mishin was asked about his period as chief designer and whether he would have done things differently. ‘Perhaps,’ he said wistfully, ‘I would have insisted on making a loop around the moon, even after the United States, because we had everything ready for it. Maybe we could have done it even before the Americans’ [15].

|

L-l, Zond series

|

L-l/Zond series: scientific outcomes

• Characterization of Earth-moon, moon-Earth space.

• Mapping of lunar farside.

• Acceptability of radiation limits for biological specimens.