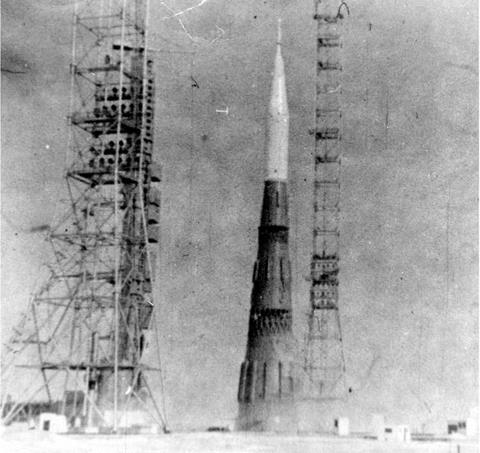

N-l ON THE PAD

By the time of these dramatic developments in Moscow, the N-l rocket was at last almost ready for launch. When rolled out in February, it was the largest rocket ever built by the Soviet Union, over 100 m tall and weighing 2,700 tonnes. The first stage, block A, would burn for 2 min on its 30 Kuznetsov NK-33 rocket engines. The second stage, block B, with eight Kuznetsov NK-43 engines, would burn for 130 sec and bring the N-l to altitude. The third stage, block V, would bring the payload into a 200 km low-Earth orbit on its four Kuznetsov NK-39 engines after a long 400 sec firing. Atop this monster was the fourth stage (block G), designed to fire the lunar complex to the moon. Block G had just one Kuznetsov NK-31 engine which would burn for 480 sec for translunar injection.

For the first-ever test of the N-l, a dummy LK lunar lander had been placed on top of block D and above it, instead of the LOK lunar orbiter, a simplified version. Called the L-1S (‘S’ for simplified), the intention was to place the L-1S in lunar orbit and then bring it back to Earth. The L-1S was, in essence, the LOK, but without the orbital module. It still carried the 800 kg front orientation engine designed for rendezvous in lunar orbit. Calculations for the mission show that with a launch on 21st February, the spacecraft would have reached the moon on 24th February, fired out of lunar orbit on the 26th and be back on Earth by the 1st March [6]. It is intriguing that this mission would have taken place simultaneously with that of the first moonrover. Indeed, the first moonrover would have landed five hours after the L-1S blasted out of lunar orbit. In a further coincidence, 1st March was the original date the Americans had set for the launch of Apollo 9. Had the USSR pulled both these missions off, assertions about ‘not being in a moon race’ would have to be creatively re-explained by the ever-versatile Soviet media.

The first N-1 went down to the pad on 3rd February. It weighed in at 2,772 tonnes, the largest rocket ever built there. It was fuelled up and the commitment to launch was now irrevocable. It was a freezing night, the temperature —41°C. At 00: 18 on 21st February the countdown of the N-1 reached its climax, the engines roared to life and the rocket began to move, ever so slowly, skyward. The launch workers cheered and even grisled veterans ofrocket launches watched in awe as the monster took to the sky. Baikonour had seen nothing like it. Safety decreed they must stand some distance away, so they could see the rocket take off several seconds before they could hear it. Seconds into the ignition, as the engines were roaring and before it had lifted off, two engines were shut down by the KORD system, but the flight was able to continue normally, just as the system anticipated. At 5 sec, a gas pressure line broke. At 23 sec, a 2 mm diameter oxidizer pipe burst. This fed oxidizer into the burning rocket stream. This caused a fire at 55 sec which had burned through KORD’s cables by 68 sec. This, shut down all the remaining engines and at 70 sec the escape system fired the L-1S capsule free, so any cosmonauts on board would have survived the failure. By then, the N-1 had reached an altitude of 27 km and, now powerless, began to fall back to Earth. The N-1 was destroyed and Alexei Leonov later recalled seeing ‘a flash in the distance and a fire on the horizon’. Some of the debris fell 50km downrange. The explosion blew windows out for miles around and Lavochkin engineers, then finishing

|

|

|

N-l on the pad |

preparations to send two probes to Mars, had to work from a windowless and now frozen hotel.

Despite the failure, the engineers were less discouraged than one might expect. First mission failures were not unusual in the early days of rocketry – indeed, as late in 1996, Europe’s Ariane 5 was to fail very publicly and embarrassingly on its first mission. Following the report of the investigating board in March, a number of changes were made, such as taking out one of the pipes that had failed, improved ventilation and moving the cables to a place where they could not be burned. The root cause of many of the failures, though, was the high vibration associated with such a powerful rocket. This could have been identified through ground-testing, but it was too late for that now. Extraordinarily enough, American intelligence did not have satellites over Baikonour that week and completely missed the launch and the fresh crater downrange.