‘A MAJOR STEP TOWARD A MANNED LANDING’

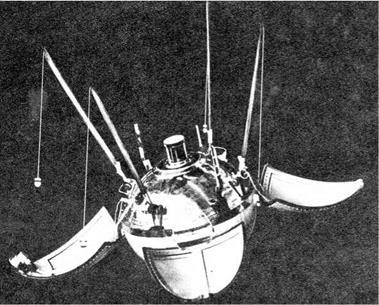

Lavochkin’s Luna 9, 1,583 kg, got away on 31st January 1966. The next day, a course correction manoeuvre was carried out, with 233,000 km still to go. Two days later, 8,300 km out, Luna 9 assumed a vertical position in the line of direction of the moon. The retrorockets blazed into life 75 km above the lunar surface for 48 sec. They cut out when the craft was a mere 250 m above the surface, its downward velocity halted. The lander, cocooned in its two airbags, was flung free to bounce over the lunar surface. The little 99.8 kg capsule settled. On the top part, four petal-like wings unfolded. Four minutes later, four 75 cm aerials poked their way out of the dome, slowly extending. Transmitters working on 183 MHz were set both on the antenna and into the petals.

|

Arnold Selivanov |

Luna 9 was down in the Ocean of Storms between the craters of Reiner and Maria, at 64.37°, 7.08°N. On Earth, ground controllers gathered that winter night, in a moment of expectation. The main module’s signals had died as it crashed. Ground controllers had to wait a very long 4 min 10 sec to know if the capsule had survived, if its instruments were still functioning and whether they would get usable information. Or would they be robbed of victory yet again?

|

Luna 9 cabin on the moon’s surface |

|

Luna 9 camera system |

They were not. It was an agonizing wait. Exactly on schedule, from the walls of the control room, where loudspeakers had been installed, flooded in the beeps, pips and humming squeal of the signals of Luna 9, direct from the surface of the moon! It was a sweet moment. For the first time a spacecraft was transmitting directly to Earth from another world! It was a historic moment and Radio Moscow lost no time in assessing its significance:

A soft-landing was one of the most difficult scientific and technical problems in space research. It’s a major step towards a manned landing on the moon and other planets.

Its importance was not lost on the West. ‘New space lead for Russia’ and ‘Russians move ahead again’ were typical headlines. Once again, America’s equivalent project called Surveyor had managed to get itself a year or two behind schedule. American engineers were quick to point out that their craft was much more sophisticated than Luna 9. Surveyor planned a real parachutist-type landing, with no rough-landing capsules and would do a more detailed job. ‘But, so what?,’ people asked. It was still in the shed.

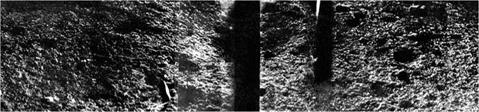

For the next few days the eyes of the world focused on the moon. At 4:50 a. m. on 4th February the television camera was switched on, a mere 60 cm above the surface. Using its mirror, it began to scan the lunar surface, a process which took 100 min through the full 360°. The camera was in fact the main instrument on board: the other

|

was a radiation recorder. A series of communication sessions was held between Earth and the moon over the next three days, which was as long as the batteries permitted. Some sessions lasted over an hour. The principal one was held on 4th February from 6:30 p. m. to 7:55 p. m. Moscow time and it sparked off a diplomatic incident. This relay was the big one – the one with the pictures. Presumably, they would be sent in code and the best would eventually be published by the Soviet media in the fullness of time.

The ever-present radio dish at Jodrell Bank, Manchester had been listening in to the Luna 9 signals all during the flight. The public relations officer at Jodrell Bank had worked in newspapers and he at once recognized the sound of the next round of signals: it was just like a newspaper’s fax machine! On an inspiration and a hunch a car was speedily despatched to Manchester to pick up the Daily Express fax machine. The car collected it, dashed back and the fax machine was at once linked up to the radio receiver and the signals from the moon. Reporters were breathless as the fax at once began converting the signals into standard newsroom photographs.

The print was passed round to observatory director Sir Bernard Lovell and the animated reporters. They could only gasp. The tall, authoritative Sir Bernard drew a deep breath and could only utter ‘amazing!’ There it was, at last – the face of the moon. The camera’s eye stretched to a sloping horizon and there loomed rocks, pebbles, stones and boulders, scattered randomly across a porous rocky surface. In the far distance was a crater dipping down. Long shadows accentuated the contrasts of the other-worldly glimpses of the moon’s stark surface.

|

|

|

|

|

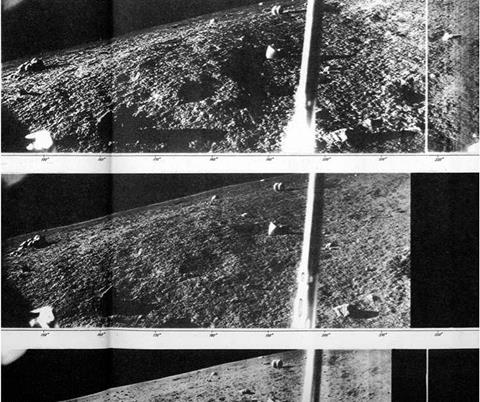

Luna 9, panoramas 1, 2, 3 |

In minutes, the world had seen the photographs. They were put out at the top of the television news and carried by every national newspapers’ front page the next day. The Russians were furious at the West scooping ‘their’ pictures. Sir Bernard was accused of sensationalism and irresponsibility. In fact, he had his scales slightly wrong (he had no means of guessing the right scale) and the real pictures were slightly flatter.

Luna 9’s transmissions were to continue for several days. Two further photographic transmissions followed, a second one on the 4th and the third on the 5th February. More photographs were picked up – eight in all – showing the lunar horizon stretching 1.4 km away in the distance and Luna 9 obviously settled into a boulder field. It was eerie, but reassuring. If Luna 9 could soft-land, then so too could a manned spacecraft: it would not suffocate in a field of dust as some had feared. As the cooling water in the spacecraft gradually evaporated, it settled its position, giving a new angle to the photos.

Its battery exhausted, Luna 9 finally went off the air forever on 6th February after transmitting 8 hr 5 min of data over seven communication sessions, of which three were photo-relays. The Ocean of Storms returned to its customary silence and

|

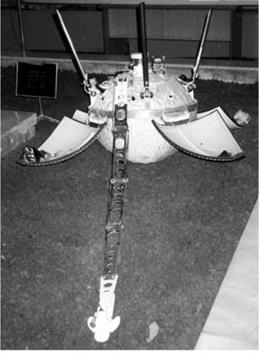

Luna 13 |

desolation. Luna 9 had done all that was asked of it: it had survived, transmitted and photographed and its timer had ensured regular broadcasts from the moon to the Earth. Another barrier to a lunar landing was down and the Americans had been beaten once again.

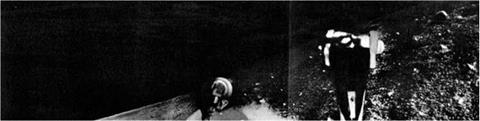

The second and final Ye-6, called the Ye-6M, was Luna 13. Luna 13 went aloft on 21st December 1966, fired its retrorockets at a distance of 69 km and bumped down onto the surface of the moon in the Ocean of Storms between the craters Craft and Selenus some 440 km distant from the Luna 9 site at 18.87°N, 62.05°W. For six days, till 28th December, it sent back a series of panoramic sweeps of surrounding craters, stones and rocks. Sun angles were low and the shadows of Luna 13’s antennae stood out against the ghostly lunarscape. Five full panoramas were returned.

Luna 13 was more advanced than its soft-landing precursor Luna 9. This was also reflected in its increased weight, 112 kg. Luna 13 carried two extensible arms which folded down like ladders onto the lunar surface. Each was 1.5 m long. At the end of one was a mechanical soil meter with a thumper which tested the density of the soil to a depth of 4.5 cm with an impulse of 7 kg and force of 23.3 kg/m2. This was developed by Alexander Kemurdzhian at VNII Transmash, the company later responsible for the development of lunar rovers. The conclusion was that moonrock was similar to medium-density Earth soil (800 kg/m3, to be precise), solid, not dusty. The moon dust was between 20 cm and 30 cm deep. At the end of the other arm was a radiation density

|

Luna 13 images |

meter which found that levels of radiation on the moon were modest and would be tolerable for humans.

Luna 13 also carried a thermometer and a cosmic particle detector. The last found that the moon absorbed about 75% of cosmic ray particles reaching the surface, reflecting the balance, 25%, back into space. The temperature of the lunar surface was measured (117°C). There was little radiation in the lunar soil itself. Table4.1 shows the key events in the Luna 13 exploration programme.