LUNAR FARSIDE PHOTOGRAPHY

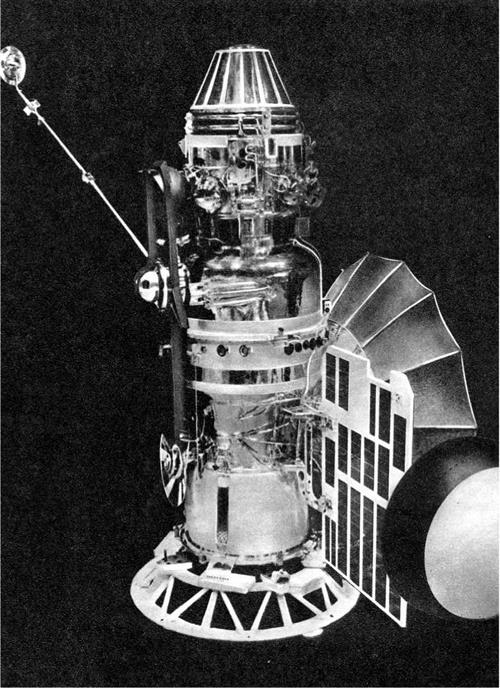

After all these Luna disappointments, it was ironic that during the summer the Soviet Union now achieved an unexpected success courtesy of an unlaunched Mars probe. This was Zond 3. The title ‘Zond’ had been contrived by Korolev to test out the technologies involved in deep space missions. Zond 1 had been sent to Venus in March 1964, while Zond 2 headed for Mars in November 1964, coming quite close to hitting the planet the following summer. These Zonds each had two modules: a pressurized orbital section, 1.1 m in diameter, with 4m wide solar panels, telemetry systems, 2 m transmission dish, a KDU-414 engine for mid-course manoeuvre and a planetary module. This could be a lander (e. g., Zond 1), but in the case of Zond 3 this was a photographic system, accompanied by other scientific instruments. The probe was compact and smaller than the Lunas at 950 kg. The camera system was a new one introduced for the 1964-5 series of Mars and Venus probes. The designer was Arnold Selivanov and his system was comparatively miniscule, weighing only 6.5 kg. The film used was 25.4mm, able to hold 40 images and could be scanned at either 550 or 1,100

|

Zond 3 |

|

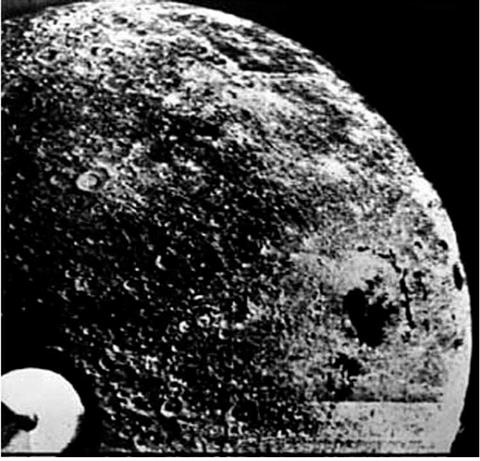

Zond 3 over Mare Orientale |

lines. Transmission could be relayed at 67 lines a second, taking only a few minutes per picture, or at high resolution, taking 34 min a picture. Additional infrared and ultraviolet filters were installed.

Zond 3 was supposed to have been launched as a photographic mission to Mars in November 1964 as well, but it had missed its launching window. Now this interplanetary probe was reused to take pictures of the moon’s farside and get pictures far superior to those taken by the Automatic Interplanetary Station in 1959 and of the 30% part of the lunar farside covered neither then nor by the April I960 failures. Taking off on 18th July 1965, nothing further was heard ofit until 15th August whena new space success was revealed. Zond 3 had shot past the moon at a distance of 9,219 km some 33 hours after launch en route to a deep space trajectory.

Photography began at 04: 24 on 20th July at 11,600 km, shortly before the closest passage over the Mare Orientale on the western part of the visible side. Well-known

|

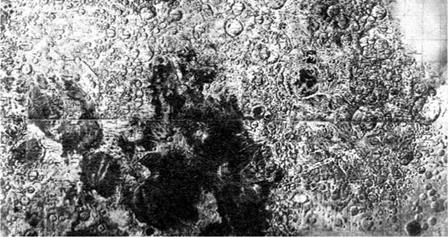

Lunar map after Zond 3 |

features of the western side of the moon were used to calibrate the subsequent features and the idea was to cover those parts of the moon not seen by the Automatic Interplanetary Station, which had swung round over the eastern limb of the moon. As Zond 3 soared over the far northwestern hemisphere of the moon, its fl06-mm camera blinked away for 68 min at l/l00th and l/300th of a second. By 05: 32, when imaging was concluded, 25 wide-view pictures were taken, some covering territory as large as 5 million km2 and, in addition, three ultraviolet scans were made. The details shown were excellent and were on l, l00 lines (the American Ranger cameras of the same time were half that).

Soviet scientists waited till Zond 3 was l.25 million km away before commanding the signals to be transmitted by remote control. They were rebroadcast several times, the last photo-relay being on 23rd October at a distance of 30 million km. There was grandeur in the photographs as Zond swung around the moon’s leading edge – whole new mountain ranges, continents and hundreds of craters swept into view. Transmissions were received from a distance of l53.4 million km, the last being on 3rd March l966. Course corrections were made using a new system of combined solar and stellar orientation.

Zond 3 had been built by OKB-l entirely in-house, not using the I-l00 control system. It was the last deep space probe designed within OKB-l, before the moon programme was handed over to Lavochkin.

With Zond 3, the primitive moon maps of the lunar farside issued after the journey of the Automatic Interplanetary Station could now be updated. Whereas the nearside was dominated by seas (maria), mountain ranges and large craters, the farside was a vast continent with hardly any maria, but pockmarked with small craters. The Russians again exercised discoverers’ prerogative to name the new features in their own language. Thus, there were new gulfs, the Bolshoi Romb and the Maly Romb (big and small) and new ribbon maria Peny, Voln and Zmei [7].

Zond 3: scientific instruments

Two cameras.

Infrared and ultraviolet spectrometer. Magnetometer.

Cosmic ray detector.

Solar particle detector.

Meteoroid detector.

Zond 3 may have encouraged the designers to believe that in their next soft-landing mission, Luna 7, they would at last meet with success. Launch was set for 4th September 1965, but faults were found in the R-7 control system and the entire rocket had to be taken back into the hangar for repairs, missing the launch window. Luna 7 left Earth the following month, on the eighth anniversary of Sputnik’s launch, on 4th October. On the second day, the mid-course correction burn went perfectly, unlike what had been the case with Luna 5 or 6. On the third day, two hours before landing and 8,500 km out, the Luna 7 orientated itself for landing. Unlike Luna 5, it was on course for its intended landing area near the crater Kepler in the Ocean of Storms. As it did so, the sensors lost their lock on the Earth and, without a confirmed sensor lock, the engine could not fire. This was the second time, after Luna 4, that the astro-navigation system had failed. Ground controllers watched helplessly as Luna 7 crashed at great speed, much as Luna 5 had done only months earlier. Investigation found that the sensor had been set at the wrong angle, in such a way that it would find it difficult to locate and hold Earthlock in the first place.

Korolev was summoned to Moscow to explain the continued high failure rate. His old patron, Nikita Khrushchev, had now been deposed and Korolev now had to deal with the new leadership around Leonid Brezhnev. Korolev admitted that there had been great difficulties and promised success the next time. Luna 8 was duly launched on 3rd December. This was the last of the Ye-6 production run of OKB- 1. Luna 8 used a new parking orbit. Its predecessors, Luna 4-7, has used a parking orbit of 65° to the equator. Now, a lower equatorial angle of 51.6° was used, making it possible to increase the mass of the spacecraft from around 1,500 kg to around 1,600 kg.

Luna 8 smoothly passed the hurdle of the mid-course correction. This time it got into a correct position for the deceleration burn and a descent to crater Kepler. Now, at this late stage, things began to go wrong. When the command was sent to inflate the airbags, a sharp bracket pierced one of them and the escaping air set the probe spinning. This blocked the system from orientating itself and the engine from firing. The probe briefly came back into position and the engine fired for 9 sec, before going out of alignment again and cutting out. A 9 sec firing instead of 46 sec clearly did little to prevent what must have been another explosive impact. The decision was taken for the future to inflate the airbags only at the very end of the deceleration burn. This was the tenth failure to achieve a soft-landing.