THE TRACKING SYSTEM

A tracking station had already been built for the moon probes of 1958-60, located in the Crimea. Its southerly location was best for following a rising moon. The Crimea around Yevpatoria offered several advantages for a tracking system. Originally, the tsars had built their summer homes around there and it had now become a resort area, meaning that it was well served by airfields. There were defence facilities in the region and military forces who could assist in construction.

The tracking system was considerably expanded in 1960. This was done to serve the upcoming programme for interplanetary exploration, but these new facilities could also be used for lunar tracking. The new construction at the Yevpatoria site was called the TsDUC, or Centre for Long Range Space Communications. The TsDUC actually comprised two stations with two receivers (downlink) and one transmitter (uplink), facilitated by a microwave station, which transmitted data from the receiver stations to another microwave system in nearby Simferopol and thence on to other locations in the USSR. The records are confusing about what was actually built at the time and where and little was said about them publicly, presumably to hide Soviet tracking capabilities from the snooping Americans. We know that the Americans had good intelligence maps of the Yevpatoria system from 1962, but it would be surprising if they had not had good details a little earlier.

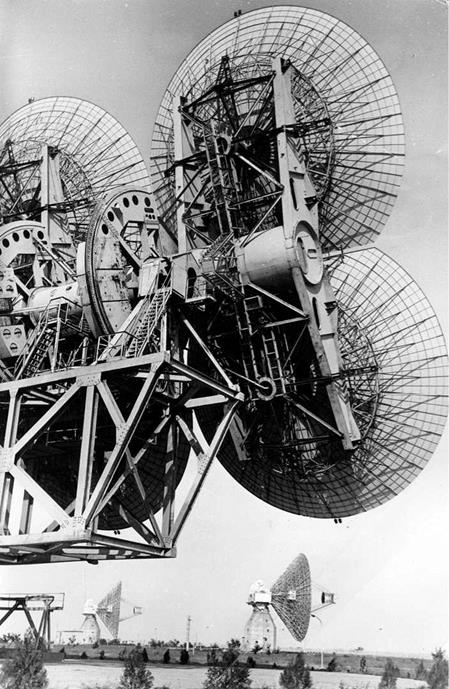

For the moment, two sets of eight individual duralium receiving dishes of 15.8 m were built on a movable structure, designed to tilt and turn in unison. Two were built 600 m apart at what the Americans called ‘North Station’ and a set of half the size, 8 m transmitting dishes called Pluton at what they called ‘South Station’. North Station was the largest complex of the two, surrounded by 27 support buildings, 15 km west of Yevpatoria. To construct the receiving stations, Korolev was forced to improvise. He came up with the idea of using old naval parts for the station: a revolving turret from an old battleship, a railway bridge for support and the hull of a scrapped submarine. They received signals on the following frequencies: 183.6, 922.763, 928.429 MHz and 3.7 GHz.

South Station was to the southeast and much closer to Yevpatoria, 9 km. It comprised one, later eight 8 m dishes in a similar configuration to, but half the size of the duo at North Station. Transmission power was rated at 120 kW and its range was estimated at 300 million km. Transmissions were sent at 768.6 MHz.

|

Dishes at Yevpatoria |

Even though chief designer Yevgeni Gubensko died in the middle of construction, Yevpatoria station went on line on 26th September I960, just in time for the first, but unlucky Mars probes. The facilities there were originally quite primitive, ground controllers being provided with classroom-style desks, surrounded by walls of computer equipment. Modern wall displays did not come in until the mid-1970s. Still, it was the most powerful deep space communications system until NASA’s Goldstone Dish came on line in 1966. In 1963, just in time for the new Ye-6 missions, the lunar programme acquired a dedicated station, a 32 m dish in Simferopol called the TNA-400.

Until a mission control was opened in Moscow in 1974, Yevpatoria remained the main control for all Russian spaceflights, not just the interplanetary ones. It was normal for the designers to fly from Baikonour Cosmodrome straight to Yevpatoria to oversee missions. The Americans, by contrast, had a worldwide network oftracking stations, with large dishes in California, South Africa and Australia. Dependence on one station at Yevpatoria imposed two important limitations on Soviet lunar probes. First, the arrival of a spacecraft at the moon had to be scheduled for a time of day when the moon was over the horizon and visible in Yevpatoria, so schedules had to be calculated with some care in advance. Second, as noted during the 1959 missions, there was no point in having Soviet moon probes transmit continuously, for their signals could not be picked up whenever the moon was out of view. Instead, there would be short periods of concentrated transmission, called ‘communications sessions’ scheduled in advance for periods when the probes would be in line of sight with Yevpatoria. This required the use of timers and sophisticated systems of control, orientation and signalling.

Korolev and his colleagues attempted to get around the limits imposed by the Yevpatoria station. If they lacked friends and allies abroad to locate tracking dishes, there were always the oceans. Here, three merchant ships were converted to provide tracking for the first Mars and Venus missions, but they could also serve the moon programme. These ships were the Illchevsk, Krasnodar and Dolinsk and their main role was to track the all-important blast out of parking orbit, which was expected to take place over the South Atlantic. The ships were a helpful addition, but they had limitations in turn. First, ships could not carry dishes as large as the land-based dishes; and, second, they were liable to be disrupted in the event of bad weather at sea, which made it difficult to keep a lock on a spacecraft in a rolling sea.