THE SOYUZ COMPLEX

These ideas were developed a stage further by another department of OKB-l, Department # 3 of Y. P. Kolyako and by Korolev himself later in 1962. Korolev was already working on a successor to the Vostok spacecraft. Korolev’s concept was for a larger spaceship than Vostok, with two cabins, able to manoeuvre in orbit and carry a crew of three. He linked his ideas to Tikhonravov’s earlier concept of orbital assembly and approved on 10th March 1962 blueprints entitled Complex for the assembly of space vehicles in artificial satellite orbit (the Soyuz), known in shorthand as the Soyuz complex. This described a multimanned spacecraft called the 7K which would link up in orbit with a stack of three propulsion modules called 9K and 11K which could send the manned spacecraft on a loop around the moon. This was endorsed by the government for further development on 16th April 1962. A second set of blueprints, called The 7K9K11K Soyuz complex, was approved on 24th December 1962. The complex was a linear descendant from the Vostok Zh design.

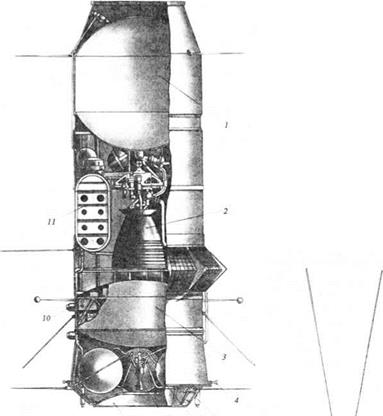

Work continued on refining the design of the Soyuz complex into the new year. On 10th May 1963, Korolev approved a definitive version, called Assembly of vehicles in Earth satellite orbit. The complex comprised a rocket block, which was launched ‘dry’ (not fuelled up) and which was the largest single unit. It contained automatic rendezvous and docking equipment and was labelled the Soyuz B; a space tanker, containing liquid fuel, called the Soyuz V; and a new manned spacecraft, called the Soyuz A. This was the system developed by Korolev, Tikhonravov and Feoktistov.

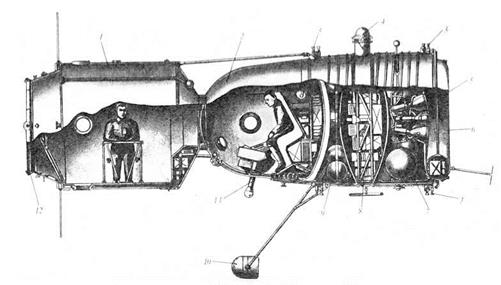

Soyuz A was a new-generation spaceship, 7.7 m long, 2.3 m diameter, with a mass of 5,800 kg. The design was radical, to say the least. At the bottom was an equipment section with fuel, radar and rocket motor. On top of this was a cone-shaped cabin for a three-man crew. Orthodox enough so far, but on top of that was a large, long cylindershaped orbital module. This provided extra cabin space (the cabin on its own would be small) and room for experiments and research. Work proceeded on the Soyuz complex into 1964 and a simulator to train cosmonauts in Earth orbit rendezvous was built in Noginsk.

Like the Vostok Zh, the Soyuz complex was aimed at flying cosmonauts around the moon without landing or orbiting. However, the Soyuz was large enough to carry two or even three men; had a cabin for observations and experiments; and the acorn

|

Soyuz complex – first block design (Soyuz A) |

cabin that could tip its heatshield in such a way as to make a skip return to Earth possible.

The sequence of events for a moon flight was as follows. On day 1, the 5,700-kg rocket block, Soyuz B, would be launched into an orbit of 226 km, 65°. It would be tested out to see that its guidance and manoeuvring units were functioning. On day 2, the first of three 6,100 kg Soyuz V tankers would be launched. Because the fuel was volatile, it would have to be transferred quite quickly. The rocket block would be the ‘active’ spacecraft and would carry out the rendezvous and docking manoeuvres normally on the first orbit. Fuel would then be transferred in pipes. After three tanker linkups, a Soyuz A manned spaceship would be launched. It would be met by the rocket block, which, using its newly-transferred fuel, would blast moonwards. The ongoing work was endorsed by government resolution on 3rd December 1963, which pressed for a first flight of the 7K in 1964 and the assembly of the Soyuz complex in orbit the following year. The first metal was cut at the very end of 1963 in the Progress machine building plant in Kyubyshev.

For the Soyuz complex, an improved version of the R-7 was defined. Glushko’s OKB-456 was asked to uprate the RD-108 motor of block A and the RD-107 motors of blocks B, V, G and D, and gains of at least 5% in performance were achieved. In OKB-154, Semyon Kosberg also uprated the third stage. An escape tower was developed by Department #11 in OKB-1. After a number of evolutions, the new rocket was given the industry code 11A511. The improved motors were tested during 1962 and entered service over 1963-4.

The Soyuz complex lunar project was a complicated profile, involving up to six launches and five orbital rendezvous. Subsequent studies show that such a mission, assuming the mastery by the USSR of Earth orbit rendezvous, was entirely feasible [3].

|

|

|

9 « 7 б J Soyuz complex – second block design (Soyuz B) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

aspect of the plan. Alexander Shargei (AKA Yuri Kondratyuk) had outlined such a method, but again it depended on a rocket much bigger than anything immediately in prospect.

Origins of the manned Soviet moon programme, 1959-64

1959 Start of studies by Mikhail Tikhonravov in Department #9, OKB-1.

1962 Vostok Zh study.

1962 First design of the Soyuz complex (10th March).

Endorsed by government (16th April).

Second set of blueprints (24th December).

1963 Definitive design of the Soyuz complex (10th May).

Approval by government (3rd December).

The design for the Soyuz complex required rendezvousing spacecraft to come within 20 km of one another on their first orbit so as to prepare for subsequent docking. This was something which the Vostok programme, limited though it was, could put to the test. On 11th August 1962, the third Vostok was put into orbit, manned by Andrian Nikolayev. Vostok 4 was put into orbit with Pavel Popovich exactly one day later, so precisely that it approached to within 5 km of Vostok 3 on its first orbit. This close approach was much better than anticipated. Both ships orbited the Earth together for three days, though unable to manoeuvre and drifting ever farther apart. In June 1963, Vostok 6, with Valentina Terreskhova on board, came to within 3 km of Vostok 5. Even though there was never any prospect of the ships coming together, the two group flights were a demonstration of how close spaceships could come on their first orbit. The cosmonauts communicated with one another during their missions and ground control learned how to follow two missions simultaneously.

Although these missions had been put together at relatively short notice and in an unplanned way to respond to the flights of the American Mercury programme, this was not at all how the missions had been interpreted in the West. The Vostok missions were seen as a carefully orchestrated series of events leading up to a flight to the moon. When Pavel Popovich joined Andrian Nikolayev in orbit, the Associated Press speculated that an attempt might be made to bring the spacecraft together before setting out on a loop to the moon. It was almost as if the agency had seen the designs of the Soyuz complex.

During the 1963 conference of the International Astronautical Federation in Paris, Yuri Gagarin told the assembled delegates:

A flight to the moon requires a space vehicle of tens of tonnes and it is no secret that such large rockets are not yet available. One technique is the assembly of parts of spaceships in near-Earth orbit. Once in orbit the components could be collected together, joined up and supplied with propellant. The flight could then begin.

This was not how the Americans were planning to go to the moon – NASA had opted for Shargei’s LOR method – and many people were skeptical as to how truthful Yuri Gagarin was actually being. The Russians must be racing the Americans to a moon

|

Nikolayev, Popovich return in triumph |

landing, they said. In fact, Gagarin was outlining, perfectly accurately, the Soviet moon plan as it stood in autumn 1963.