THE BIG RED LIE?

The First Cosmic Ship was denounced in some quarters of the Western world as a fraud and one writer, Lloyd Malan, even wrote a book about it called The big red lie.

|

Following the First Cosmic Ship |

The reason? Few people in the West picked up its signals, even though the Russians had, as usual, announced their transmission frequencies (183.6, 19.993 and 19.997 MHz). Not only that, but the original Tass communique announcing the mission had told observers when the moonship would be over Hawaii, when the sodium cloud would be released and even where to look for it (the constellation Virgo).

The explanations were mundane, rather than conspiratorial. The Russians had inconveniently launched the First Cosmic Ship late on a Friday night and most professional observers had long since gone home for the weekend. By the time the Earth had rotated in line of sight for American observatories, the First Cosmic Ship was already well on its way and ever more difficult to pick up. In the event, signals were received on the next day by Stanford University in California when it was about 171,000 km out. At the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, staff were recalled over the weekend in a frantic effort to locate the spacecraft, which they eventually did when it was 450,000 km out, eight hours after it passed the moon. American military signal stations probably also tracked the spacecraft in Hawaii, Singapore, Massachusetts and Cape Canaveral, but if they received signals, they never told.

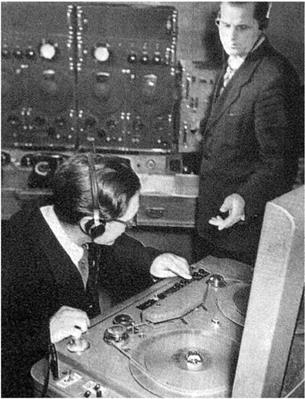

In Britain, the director of the large radio telescope at Jodrell Bank, Bernard Lovell, was at home listening to Johann Sebastian Bach’s Fantasy and fuge. Jodrell Bank had been established by a physics professor, Bernard Lovell, who had spent the war developing radar to detect enemy planes and ships. In peacetime, he now adapted ex-army radars to study cosmic rays and meteor trails. This work was so promising that in 1950 he got the go-ahead for a large radio telescope for radio mapping of deep space objects and this was, fortuitously, completed just in time for the launching of Sputnik seven years later. There was some debate in Jodrell Bank as to whether the huge dish telescope should be used to track spacecraft at all, but the station had considerable financial liabilities and the glow of world media publicity attached to the station’s role in tracking spacecraft soon enabled that debt to be cleared. In fact, it was not the Russians but the Americans who first brought Jodrell Bank into the moon programme, paying for the use of its facilities in 1958 for the early American moon probes. Jodrell Bank had tried but failed to pick up the First Cosmic Ship, but, Bernard Lovell added, the station still believed that the probe existed! He put down his failure to obtain signals as due to inexperience. He had imagined that it would transmit continuously and had not understood the Russian system of periodic transmission, the ‘communications session’ [6].

The early moon shots of the United States and the Soviet Union had much in common. The first and the most obvious was their high failure rate. With the successful launching of the First Cosmic Ship, Russia and America had each tried four times. One Russian probe had reached but missed the moon. One American probe had reached 113,000 km, the other 102,000 km before falling back. All the rest had exploded early on.

Here, the similarities ended. The Russian Ye-1 probe was large, weighing 156 kg, with a simple (albeit elusive) objective: to impact on the moon. Six instruments were carried. By contrast, the American Pioneer probes were tiny, between 6 kg and 39 kg. They carried similar instruments: for example, like the early Russian probes, Pioneer 1 carried a magnetometer. The early American missions were more ambitious, aiming for lunar orbit and to take pictures of the surface of the moon. The camera system on Pioneer was tiny, weighing only 400 g, comprising a mirror and an infrared thermal radiation imaging device.

The First Cosmic Ship was hailed as a great triumph in the Soviet Union. The third year of space exploration could not have opened more brightly. Stamps were issued showing the rocket and its ball-shaped cargo curving away into a distant cosmos.