ONLY HOURS APART: THE MOON RACE, AUTUMN 1958

By this time, the United States had launched their first satellite (Explorer 1, January 1958) and had made rapid progress in preparing a lunar programme. Korolev followed closely the early preparations by the United States to launch their first moon probe, called Pioneer. Learning that Pioneer was set for take-off on 17th August 1958, Korolev managed to get his first lunar bound R-7, with its brand-new Kosberg upper stage, out to the pad the same day, fitted with a Ye-1 probe to hit the lunar surface. The closeness of these events set a pattern that was to thread in and out of the moon programmes of the two space superpowers for the next eleven years.

There had been a lot of delays in getting the rocket ready and Korolev only managed to get this far by working around the clock. The lunar trajectory mapped out by Korolev and Tikhonravov was shorter than Pioneer. Korolev waited to see if Pioneer was successfully launched. If it was, then Korolev would launch and could still beat the Americans to the moon. Fortunately for Korolev, though not for the Americans, Pioneer exploded at 77 sec and a relieved Korolev was able to bring his rocket back to the shed for more careful testing.

A month later, all was eventually ready. The first Soviet moon probe lifted off from Baikonour on 23rd September 1958. Korolev may have worried most about whether the upper stage would work or not, but the main rocket never got that far, for vibration in the BVGD boosters caused it to explode after 93 sec. Despite launching three Sputniks into orbit, the R-7 was still taking some time to tame. Challenged about

|

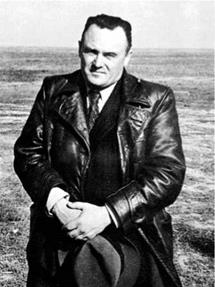

Sergei Korolev at launch site |

repeated failures and asked for a guarantee they would not happen again, Korolev lost his temper and yelled: Do you think only American rockets explode?

The August drama came around a second time the following month. At Cape Canaveral, the Americans counted down for a new Pioneer, with the launch set for 11th October. In complete contrast to the developments at Cape Canaveral, which were carried out amidst excited media publicity, not a word of what was going on in Baikonour reached the outside world. Again, Korolev planned to launch the Ye-1 spaceship on a faster, quicker trajectory after Pioneer. News of the Pioneer launching was relayed immediately to Baikonour, Korolev passing it on in turn over the loudspeaker.

Not long afterwards, the news came through that the Pioneer’s third stage had failed. Korolev and his engineers now had the opportunity to eclipse the Americans. On 12th October, his second launching took place. It did only marginally better than the previous month’s launch, but the vibration problem recurred, blowing the rocket apart after 104 sec. Although Pioneer 1 was launched thirteen hours before the Soviet moon probe was due to go, the Russian ship had a shorter flight time and would have overtaken Pioneer at the very end. Korolev’s probe would have reached the moon a mere six hours ahead of Pioneer. According to Swedish space scientist and tracker Sven Grahn who calculated the trajectories many years later, ‘the moon race never got much hotter!’.

These two failures left Korolev and his team downcast. Although the R-7 had given trouble before, two failures in a row should not be expected, even at this stage of its development. Boris Petrov of the Soviet Academy of Sciences was appointed to head up a committee of inquiry while the debris from the two failures was collected and carefully sifted for clues. What they found surprised them. It turned out that the Kosberg’s new upper stage, even though it had never fired, was indirectly to blame. The new stage, small though it might be, had created vibrations in the lower stage of the rocket at a frequency that had caused them to break up. This was the first, but far from the last, time that modification to the upper stages of rockets led to unexpected consequences.

Devices were fitted to dampen out the vibration. Although they indeed fixed this problem, the programme was then hit by another one. It took two months, working around the clock, to get a third rocket and spacecraft ready. The third rocket took off for the moon on 4th December. As it flew through the hazardous 90-100 sec stage, hopes began to rise. They did not last, for at 245 sec, the thrust fell to 70% on the core stage (block A) and then cut out altogether. The rocket broke up and the remnants crashed downrange. The crash was due to the failure of a hydrogen peroxide pump gearbox, in turn due to the breaking of a hermetic seal which exposed the pump to a vacuum. It must have been little consolation to Korolev that the next American attempt, on 6th January, was also a failure, though it reached a much higher altitude, 102,000 km.

The Soviet failures were unknown except to those directly involved and the political leadership. America had experienced its own share of problems, but there the mood was upbeat. The probes had a morale-boosting effect on American public opinion. There was huge press coverage. The Cape Canaveral range (all it had been to date was an air force and coastguard station) became part of the American consciousness. Boosters, rockets, countdowns, the moon, missions, these words all entered the vocabulary. America was fighting back, and if the missions failed, there were credits for trying.

On the Russian side, there was little public indication that a moon programme was even under way. In one of the few, on 21st July 1957, Y. S. Khlebstsevich wrote a speculative piece outlining how, sometime in the next five to ten tears, the Soviet Union would send a mobile caterpillar laboratory or tankette to rove the lunar surface and help choose the best place for a manned landing [2]. Information about the Soviet space programme, which had been relatively open about its intentions in the mid-1950s, now became ever more tightly regulated. Chief ideologist Mikhail Suslov laid down the rubric that there could not be failures in the Soviet space programme. Only successful launchings and successful mission outcomes would be announced, he decreed, despite the protests at the time and later of Mstislav Keldysh. A cloud of secrecy and anonymity descended. The names of Glushko and Korolev now disappeared from the record, although they were allowed to write for the press under pseudonyms. Sergei Korolev became ‘Professor Sergeev’. Valentin Petrovich Glushko’s nom deplume was only slightly less transparent: ‘Professor G. V. Petrovich’, for it used both his initials (in reverse) and his patronymic.

So whenever spaceflights went wrong, their missions were redefined to prove that they had, indeed, achieved all the tasks set for them. This was to lead Soviet news management, in the course of lunar exploration, into a series of contradictions, blunders, disinformation, misinformation and confusion. But it was best, as in the case of the first three moonshots, that nothing be known about them at all.