THE POSTWAR MOBILIZATION

Neither the Russians, Americans, British nor French were under any misapprehensions about the achievement of von Braun and his colleagues. Each side dispatched its top rocket experts to Germany to pick over the remains of the A-4. For one brief moment in time, all the world’s great rocket designers were within a few kilometres of each another. Von Braun was there, though busily trying to exfiltrate himself to America. For the Soviet Union, Valentin Glushko, Sergei Korolev, Vasili Mishin, Georgi Tyulin and Boris Chertok. For the United States, Theodor von Karman, William Pickering and Tsien Hsue Shen (who eventually became the founder of the Chinese space programme). Later in 1945, Britain was to fire three V-2s over the North Sea. Britain’s wartime allies were invited to watch. The British admitted one ‘Colonel Glushko’ but they refused admittance to another ‘Captain Korolev’ because his paperwork was not in order and he had to watch the launching from the perimeter fence. The British were not fooled by these civilians in military uniforms, for they could give remarkably little account of their frontline experience (or wounds) in the course of four years’ warfare.

Korolev and Glushko returned to Russia where Stalin put them quickly to work to build up a Soviet rocket programme. The primary aim was to develop missiles and if the engineers entertained ambitions for using them for space travel, they may not have kept Stalin so fully informed. The rocket effort was reorganized, a series of design bureaux being created from then onwards, the lead one being Korolev’s own, OKB-1. Glushko was, naturally, put in charge of engines (OKB-456). In 1946, the Council of Designers was created, Korolev as chief designer. This was a significant development, for it included all the key specialisms necessary for the later lunar programme: engines (Valentin Glushko), radio systems (Mikhail Ryazansky), guidance (Nikolai Pilyugin), construction (Vladimir Barmin) and gyros (Viktor Kuznetsov). In 1947, the Russians managed to fire the first of a number of German A-4s from a missile base, Kapustin Yar, near Stalingrad on the River Volga. The Russian reverse-engineered version was called the R-1 (R for rocket, Raket in Russian) and its successors became the basis for the postwar Soviet missile forces. Animals were later launched on up-and-down missions on later derivatives, like the R-5.

The significant breakthrough that made possible the development of space travel was an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). In the early 1950s, as the Cold War intensified, the rival countries attempted to develop the means of delivering a nuclear payload across the world. The ICBM was significant for space travel because the lifting power, thrust and performance required of an ICBM was similar to that required for getting a satellite into orbit. In essence, if you could launch an ICBM, you could launch a satellite. And if you could launch a satellite, you could later send a small payload to the moon.

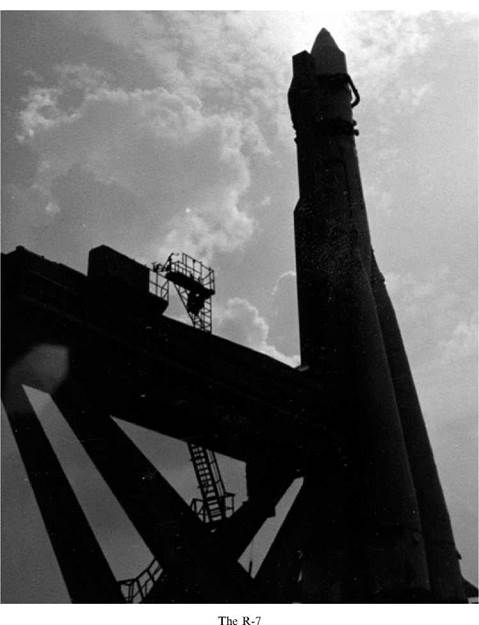

Approval for a Soviet ICBM was given in 1953. An ICBM in the 1950s was a step beyond the A-4, as much as the A-4 of the 1940s was a step beyond the tiny amateur rockets of the 1930s. Korolev was the mastermind of what became known as the R-7 rocket. It was larger than any rocket built before. It used a fuel mixture of liquid oxygen and kerosene, a significant improvement on the alcohol used on the German A-4. Its powerful engines were designed and built by Valentin Glushko, whose own design bureau, OKB-456, was now fully operational. The real breakthrough for the R-7 was that in addition to the core stage with four engines (block A), four stages of similar dimensions were grouped around its side (blocks B, V, G and D). This was

|

|

called a ‘packet’ design – an idea of Mikhail Tikhonravov dating to 1947 when he worked for NII-4. No fewer than 20 engines fired at liftoff. Work began on this project over 1950-3.

The new rocket required a new cosmodrome. Kapustin Yar was too close to American listening bases in Turkey. A new site was selected at Tyuratam, north of a

bend in the Syr Darya river, deep in Kazakhstan. The launch site was called Baiko- nour, but this was a deliberate deception. Baikonour was actually a railhead 280 km to the north, but the Russians figured that if they called it Baikonour and if nuclear war broke out, the Americans would mistakenly target their warheads on the small, undefended unfortunate railway station to the north rather than the real rocket base. Construction of the new cosmodrome started in 1955, the labourers living and working in primitive and hostile conditions. Their first task was to construct, out of an old quarry, a launch pad and flame pit. The first pad was built to take the new ICBM, the R-7.

Scientific direction for the space programme was provided by the Academy of Sciences. The Academy dated back to the time of Peter the Great. Following the European tradition, he established a centre of learning for Russia’s academic community in St Petersburg. This had survived the revolution, though now it was renamed the Soviet Academy of Sciences. For the political leadership’s point of view, the Academy provided a visible and acceptable international face for a space programme that had its roots in military imperatives. The chief expert on the space programme within the Academy of Sciences was Mstislav Keldysh, a quiet, graying, mathematical academician. Mstislav Keldysh was son of Vsevolod M. Keldysh (1878-1965), one of the great engineers of the early Soviet state, the designer of the Moscow Canal, the Moscow Metro and the Dniepr Aluminium Plant. Young Mstislav was professor of aerohydrodynamics in Moscow University, an academician in 1943 at the tender age of 32 and from 1953 director of the Institute of Applied Mathematics. Following Stalin’s death, he had introduced computers into Soviet industry. He was on the praesidium of the Academy from 1953, won the Lenin Prize in 1957 and later, from 1961 to 1975, was academy president. He was the most prestigious scientist in the Soviet Union, though he made little of the hundreds of awards with which he was showered in his lifetime. His support and that of the academy for Korolev and Tikhonravov was to become critical.

In the 1950s, the idea of a Russian space programme enjoyed discussion in the popular Soviet media. The golden age of the 1920s had come to an abrupt end in 1936 and talking about space travel remained dangerous as long as Stalin ruled the Kremlin. When the political environment thawed out, ideas around space travel once again flourished in the Soviet media – newspapers, magazines and film. Soviet astronomers resumed studies that had been interrupted by the war. A department of astrobotany was founded by the Kazakh Academy of Sciences and its director, Gavril Tikhov, publicized the possibililities of life on Mars and Venus. His books were wildly popular and he toured the country giving lectures.

By 1957, the key elements of the Russian space programme were in place:

• A strong theoretical base.

• Practical experience of building engines from the 1920s and small rockets from the

1930s.

• A council of designers, led by a chief designer.

• A lead design bureau, OKB-1, with a specialized department, #9.

• Specialized design bureaux for all critical support areas, such as engines.

• An academy of sciences, to provide scientific direction.

• Launch sites in Kapustin Yar and Baikonour.

• Popular and political support.

• A large rocket, completing design.

REFERENCES

[1] Gorin, Peter A: Rising from the cradle – Soviet public perceptions of space flight before Sputnik. From: Roger Launius, John Logsdon and Robert Smith: Reconsidering Sputnik – 40 years since the Soviet satellite. Harwood Academic, Amsterdam, 2000.

[2] Siddiqi, Asif: Early satellite studies in the Soviet Union, 1947-57. Part 2. Spaceflight, vol. 39, #11, November 1997.

[3] Siddiqi, Asif: The decision to go to the moon. Spaceflight,

– vol. 40, # 5, May 1998 (part 1);

– vol. 40, #6, June 1998 (part 2).

[4] Varfolomeyev, Timothy: Soviet rocketry that conquered space. Spaceflight, in 13 parts:

1 Vol. 37, #8, August 1995;

2 Vol. 38, # 2, February 1996;

3 Vol. 38, #6, June 1996;

4 Vol. 40, #1, January 1998;

5 Vol. 40, #3, March 1998;

6 Vol. 40, # 5, May 1998;

7 Vol. 40, #9, September 1998;

8 Vol. 40, #12, December 1998;

9 Vol. 41, #5, May 1999;

10 Vol. 42, # 4, April 2000;

11 Vol. 42, #10, October 2000;

12 Vol. 43, #1, January 2001;

13 Vol. 43, #4, April 2001 (referred to as Varfolomeyev, 1995-2001).

[5] Harford, Jim: Korolev – how one man masterminded the Soviet drive to beat America to the moon. John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1997.

[6] Khrushchev, Sergei: The first Earth satellite – a retrospective view from the future. From: Roger Launius, John Logsdon and Robert Smith: Reconsidering Sputnik – 40 years since the Soviet satellite. Harwood Academic, Amsterdam, 2000.

[7] Matson, Wayne R: Cosmonautics – a colourful history. Cosmos Books, Washington DC, 1994.

[8] Siddiqi, Asif: The challenge to Apollo. NASA, Washington DC, 2000.