THE HIATUS IN SOVIET MARS MISSIONS: 1974^1988

By early 1974 the Soviet space program was severely traumatized. Its manned lunar program had failed both to beat the IJS to a circumlunar flight and to introduce into service the N-l, its answer to the Saturn V launcher, meant to dispatch cosmonauts to land on the Moon. It had taken second prize with robotic lunar rovers and sample return missions. The all-out Mars effort of 1973 had been an embarrassing failure. In May, Vasily Mishin. Sergey Korolev’s protege and successor, was replaced as Chief Designer by the avowed rival to both, Valentin Glushko, who canceled the N-l and refocused the manned program on a new Energiya launcher and the Buran reusable spaceplane to compete with the space shuttle the US had recently started to develop.

In the early 1970s a "war of the worlds’* had raged in the community of Soviet scientists and engineers working on planetary exploration. The Venusians’ argued for concentrating on Venus where they felt the USSR had a clear advantage, instead of challenging the US wiiere it had gained the advantage. Of course, the "Martians* argued to focus on Mars as the more interesting of the tw o planets. They could not compete with the sophisticated Viking landers, but studies had been underway for several years for a bold and even more prestigious mission to Mars a sample return that w ould require the N-l lunar rocket. The debate w as between Roald Sagdeev, the Director of IKI, and Alexander Vinogradov, Director of the Vernadsky Institute of Geochemistry. Vice President of the Academy of Sciences and Chair of the Lunar and Planetary Section of the Academy’s Inter-Department Scientific and Technical Council on Space Exploration. The ultimate arbiter w;as Mstislav Keldysh, who was scientifically the most acknowledged and most politically well connected member of the community. Keldysh hesitated over the very ambitious plans of the "Martians* and eventually took the practical route by turning to Venus for the immediate launch opportunities. NPO-Lavochkin was allowed to continue designing Mars rovers and sample return missions that w’ould use the Proton launcher, but by 1975 76 these w ould prove impractical. Instead, Sergey Kryukov, who had taken over from Gcorgi Babakin on the latter’s death in August 1971, proposed to salvage the Mars program with a less ambitious mission to Phobos, the larger of the planet’s two small moons. Keldysh w’as supportive of this concept, but it w ould fade after Kryukov resigned in 1977 and Keldysh died in 1978, and the ‘Martians* had to stand down wiiile Venus look center stage for the next ten years.

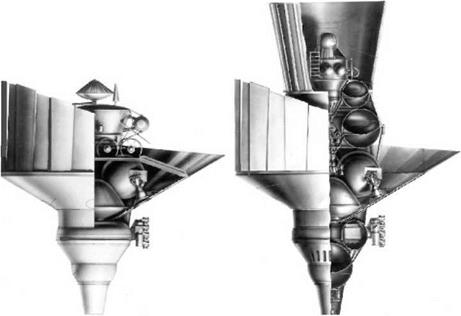

Nonetheless, it is interesting to describe in some detail the very ambitious plans of the ‘Martians’ at that time. Soviet engineers had been working on designs for Mars sample return missions in parallel with developing the Mars spacecraft for the 1971 and 1973 campaigns. Bolstered by the success of the Luna 16 sample return and the Luna 17 lunar rover missions in 1970, the “top brass” ordered NPO-Lavochkin to fly a Mars sample return mission by mid-decade. Kryukov assumed that the N-l would be available. The first spacecraft design had a launch mass of 20 tons. The 16 ton entry system used an 11 meter acroshell with folding petals to enable it to fit inside the payload shroud. The lander eschewed parachutes and used large retro – rockets to decelerate. A direct return to Earth was planned with a spacecraft based on the 3MV design of Venera 4 to 6, using a two-stage rocket and an entry capsule which would deliver 200 grams of Martian soil to Earth. The Soviets w’restlcd with the complexity of the spacecraft system and also with the issue of biological contamination of Earth. A test mission was tentatively planned for 1973 that would deliver to the surface of Mars a rover based on the successful Lunokhod.

The failure of the N-l rocket program forced a change to a less massive design. In 1974 NPO-Lavochkin began to consider how to use the Proton to accomplish a Mars sample return mission. Two Protons would be used. The first would place a Block D upper stage and the spacecraft into Earth orbit and the second would orbit a second Block D that would rendezvous and dock. The two propulsive stages would then be fired in succession to send a flyby /lander spacecraft to Mars. Spacecraft mass would be saved by not requiring the sample return vehicle to fly directly back to

|

Figure 13.13 Mars rover (left) and sample return (right) concepts for launch on the N-l rocket. |

Earth but instead to enter Mars orbit, where it would rendezvous with an Earth – return vehicle that had been launched by a third Proton. And in one scenario, instead of entering the atmosphere the return vehicle w ould brake into a low Earth orbit for retrieval by a manned mission. Again a precursor mission for landing a rover on Mars w? as planned.

The project wrestled with continuing issues of complexity and mass. This led to a refinement in 1976 in which the first spacecraft would be launched into Earth orbit with its Block D upper stage dry, so as to allow’ for increased spacecraft mass. The second launch would deliver both a second Block D and fuel for transfer into the dry stage. The flybv/lander spacecraft launch mass was 9,135 kg. The flyby spacecraft w7as 1,680 kg, and the entry system 7,455 kg including 3,910 kg for the two-stage surface-to-orbit vehicle and 7.8 kg for the Earth return capsule, which in this version would pass through the atmosphere without having either a parachute or a telemetry system. The struggle to accommodate the complexity, cost and risk of this mission strained Soviet technology beyond its limits. At the same time, NPO-Lavochkin was continuing to mount complex lunar rover and sample return missions through 1976. The results from the considerable funds that were expended on designing these Mars missions were disappointing. Other programs, including a Lunokhod 3 mission, had to be sacrificed. When it became apparent that the project w? as impractical, it w’as canceled and Kryukov was transferred.

While successful at automated lunar sample return, the Soviet Union never got the chan ее to try a Mars sample return mission. In the mid-1970s the space ambitions of both nations were thwarted by their respective governments. In addition to losing the race to the Moon the Soviets had suffered appalling failures at Mars. Performance and cost became serious issues, and risk was less tolerable. Ironically, the result in the US w7as the same despite the success of the Apollo program and the Vikings at Mars. It would be a long time before either nation sent another mission to Mars but once again it w’as the Soviets who were the first to do so, with the Phobos missions of 1988. In the meantime, having taken the lead in planetary exploration in the 1970s by exploring from Mercury to Neptune, America fell behind again in the 1980s as their planetary launch rate dropped to zero and the Soviets reaped success after success at Venus and opened up their program to international cooperation with complex science-dense missions at Venus, Halley’s comet, and finally Mars.