ПІЕ ZOND CIRCUMLUNAR SERIES: 1967-1970

Campaign objectives:

After the August 1964 government declaration that divided the work on the Soviet manned lunar program between Chelomey’s Proton-launched cir cum lunar program and Korolev s N-l launched lander program, Korolev continued throughout the year to argue for both to be consolidated under his ОКБ-1. In addition to organizational and economic arguments, he offered the prospect of reaching the Moon much sooner with a spacecraft already in an advanced stage of design, whereas Chelomey would have to start from scratch. For the circumlunar mission Korolev proposed a stripped down form of his Earth orbital Soyuz complex w hich, as it happened, w^as originally conceived wath lunar missions in mind. The anxiety to get a Soviet cosmonaut to the Moon first, and Korolev’s persuasiveness, won him a partial victory in October 1965 when the government approved his 7K-L1 lunar Soyuz for circumlunar flights that would be launched by Chelomey’s Proton using OKB-l’s Block D as an upper stage. The N-l was neither ready nor appropriate for circumlunar missions, it was for the manned lunar landing program. Although rivals, Korolev and Chelomey appeared to work together well in implementing this circumlunar plan. Meanwhile Korolev would continue to develop the hardware for the manned lunar landing program: the N-l launcher, the LOK lunar orbital version of the Soyuz, and the LK lunar lander.

7K-L1 No.4L

7K-L1 No.4L

Cireumliinar and Return Test Flight

USSR TsKBEM

Proton-K

September 27. 1967 at 22:11:54 UT (Baikonur) Booster destroyed.

7K-L1 No.5L

Circumlunar and Return Test Flight

USSR/TsKBCM

Proton-K

|

Launch Date ‘: 7 "une: Outcome: |

November 22. 1967 at 19:07:59 UT (Baikonur) Second stage destroyed |

|

Third spacecraft: Mission Type: Country; Builder: Launch Vehicle: Launch Date: Time: Return Date ІI ime: Outcome: |

Zond 4 (7 К-LI No.6L) Test Flight to Lunar Distance and Return USSR TsKBHM Proton-K March 2, 1968 at 18:29:23 UT (Baikonur) March 9, 1968 Spacecraft self-destructed while on parachutes. |

|

Fourth spacecraft: Mission Type: Country: Builder: Launch Vehicle: Launch Date! Time: Outcome: |

7K-L1 No.7L Circumlunar and Return Test Flight USSR TsKBHM ^ Proton-K April 22, 1968 at 23:01:27 UT (Baikonur) Failed due to second stage shutdown. |

|

Fifth spacecraft: Mission Type: Country j Builder: Launch Vehicle: Launch Date ‘: 7 ime: Em•ounier Da tej Time: Return Date! Time: Outcome: |

Zond 5 (7K-L1 No.9L) Circumlunar and Return Test Flight USSRTsKBEM Proton-K September 14. 1968 at 21:42:11 UT (Baikonur) September 18. 1968 September 21. 1968 at 16:08 UT Successful recovery in Indian Ocean. |

|

Sixth spacecraft: Mission Type: Country і Builder: Launch Vehicle: Launch Dateі 7 7me: Encoun ter Date/ Time: Re turn Date/ Time: Outcome: |

Zond 6 (7K-L1 No. l2L) Circumlunar and Return Test Flight USSRTsKBEM Proton – K November 10. 1968 at 19:11:31 UT (Baikonur) November 14. 1968 November 17. 1968 Spacecraft crashed on return landing in Kazakhstan. |

|

Seventh spacecraft: Mission Type: Country j Builder: Launch Vehicle: Launch Date: Time: Outcome: |

7K-L1 No. l3L Test Flight to Lunar Distance and Return USSRTsKBEM Proton-K January 20, 1969 at 04:14:36 UT (Baikonur) Upper stages failed. |

|

Eighth spacecraft: Mission type: Country і Builder: Launch Vehicle: Launch Date/ Time: Encoun ter Date; 7 ‘ime: Re turn Date / Time: Outcome: |

Zond 7 (7K-L1 No. 11) Circumlunar and Return Test Flight USSR TsKBEM Proton-K August 7. 1969 at 23:48:06 UT (Baikonur) August 11, 1969 August 14, 1969 Successful recovery in Siberia. |

Zond 8 (7K-L1 No.14)

Circumlunar and Return Test Flight

Circumlunar and Return Test Flight

USSR TsKBEM

Proton-K

October 20, 1970 at 19:55:39 UT (Baikonur) October 24. 1970 October 27. 1970 at 13:55 UT Successful recovery in Indian Ocean.

It was decided to make the test flights of the lunar versions of the Soyu/ in the Zond series, beginning with the 7K-L1 circumlunar model launched by the Proton. Approved in December 1966, the plan for the LI program called for four automated tests prior to the first manned circumlunar flight, which was scheduled for launch on June 26, 1967. The follow-on series was intended to test the 7K-LOK lunar orbital model launched by the N-l lunar rocket, the Soviet counterpart to the Saturn V. This extensive flight testing in the manned program was unique to the Soviets. Ironically, Korolev generally eschewed full-up piloted flight tests in the manner of Apollo, but he abhorred the extensive ground testing the US conducted in all its programs. As a result, Soviet spacecraft generally had a much higher degree of automation than US spacecraft, often to the chagrin of the cosmonauts, and the lack of ground testing led to poor performance in test flights and consequent failures and delays.

The success of Zond 5 in circumnavigating the Moon, returning to Earth and then being recovered in September 1968 set of!’ celebrations in the USSR. It was the first mission of either nation to achieve this feat. Shortly afterwards the Soviets revealed that it was an automated flight of a Soyuz manned capsule. This set off alarms in the US, because the way seemed clear for a cosmonaut to Пу the same mission. There were windows in November and mid-December which would enable the Soviets to steal a march on Apollo 8. whose launch window was in late December. (A window Гог the northerly Baikonur site opened slightly earlier than for the lower latitude site in Florida.) The Soviets used the November window for another test, but Zond 6 Tailed catastrophically during landing. Unaware of this setback the US expected a Soviet manned circumlunar mission in December, but there was no such launch. The way was now clear for Apollo 8. The Soviets had insisted on four successful automated flights of Zond prior to a manned mission. There had been an internal debate on whether it would be justified to make an attempt as reckless as the Soviets Гек the Americans were making with a mission to orbit the Moon using the first manned Saturn V. The failure of Zond 6 rendered this debate moot. After Apollo 8 the Soviets doggedly continued to perfect Zond for the circumlunar mission, but switched their focus and rushed tests of the N-l launcher.

Although most Zond test flights were designed to provide information on the techniques and technologies needed to fly cosmonauts to the Moon and back safely, they also provided information of scientific interest. Instrumentation flown on these missions gathered data on micrometeoroid flux, solar and cosmic rays, magnetic

fields, radio emissions, and the solar wind. Biological payloads were also flown and many excellent photographs of the Moon and Earth were taken.

Spacecraft:

The Soyuz 7K-L1 was a version of the 7K-LOK lunar orbital spacecraft modified to perform a circumlunar mission. Lacking an orbital module, it would have carried two rather than three cosmonauts. It had redesigned instrument panels for lunar missions and a thicker heat shield to handle the faster re-entry from a lunar return. There were a number of other design differences for the circumlunar missions.

Zond 4 is notable for being the first Soviet spacecraft to possess a computer. The 34 kg Argon 11 used integrated circuits, drew 75 W, was capable of 15 operations, and was provided with 4K of instruction ROM and 128 words of RAM.

Zond launch mass: ~ 5,375 kg

|

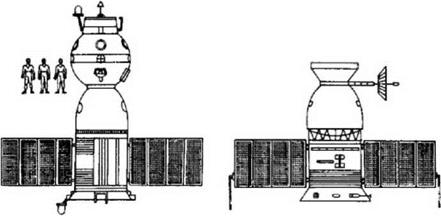

Figure 10.18 Comparison of Soyuz at left and Zond at right (from Space Travel Encyclopedia). |

Payload:

Zonds 5 to 7:

1. Imaging system (color on Zond 7)

2. Cosmic ray detectors

3. Micrometeoroid detectors (Zond 6 only)

4. Biology payload

|

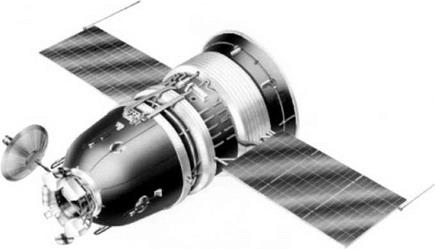

Figure 10.19 Zond 4 to Zond 8 spacecraft (courtesy Energiya Corp). |

Zond 8:

1. Imaging system

2. Solar wind collector

The imaging systems on Zond 5, 6 and 8 carried a 400 mm camera for 13 x 18 cm frames of lsopanchromalic film. Zond 7 carried a 300 mm camera using 5.6 x 5.6 an film, both panchromatic and color. The solar wind collector utilized aluminum foil targets similar to the solar wind collectors that xA. pollo astronauts set up on the lunar surface, except that in the case of the Zond missions they were on the exterior of the descent capsule.

Mission description:

The constraints for circumlunar flights with launch and recovery in the high latitudes of the Soviet Union were fairly severe, yielding only 5 or 6 launch opportunities per year and not always spread out evenly over the year. Hence some Zond tests were made out to lunar distance without the Moon being available. Before the automated circumlunar series, there were two Earth orbital test flights. The first, launched on March 10, 1967, was only the fifth flight of the Proton and the first with Korolev’s Block D fourth stage. It successfully placed the Soyuz into an orbit with an apogee far from Earth and telemetry tests were carried out. No recovery was attempted. The mission, designated Cosmos 146, was an auspicious start. The schedule for the first manned circumlunar flight in June 1967 seemed feasible. But then everything went wrong. The second flight test on April 6, 1967, went awry when the Block D failed.

Worse, on April 23 the first manned Earth orbital flight of the Soyuz failed when it crashed upon landing, killing cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov. His brief orbital flight had been plagued with serious problems and in attempting an emergency landing the parachute became entangled. Both the Zond and Soyuz programs stood down while the common issues were addressed. By September the Zond program was ready to resume.

The first two circumlunar mission attempts fell victim to the Proton launcher. In the first on September 27, 1967. one of the six engines on the booster failed to ignite owing to a blocked propellant line and the rocket was destroyed 97 seconds into the flight. Pad engineers had not removed a cover before flight. On the second launch on November 22, 1967. one of the four engines on the second stage failed to ignite at 125 seconds into the flight and the rocket was destroyed at the 130 second mark.

The next launch had been scheduled for a window7 in April 1968, but the Soviets were anxious to finish testing and beat the US to the Moon so it w7as decided to go early, without the Moon, and test the spacecraft to lunar distance with the high speed re-entry. On March 2. 1968, Zond 4 w7as launched into a highly elliptical orbit with an apogee al 354.000 km. ll suffered many in flight system failures. An erratic star tracker in the attitude control system complicated the flight, but engineers managed to navigate the spacecraft back to Earth. The sensor failed again in the automated re-entry sequence, resulting a ballistic rather than the intended guided descent. While descending on its parachute over the Gulf of Guinea the capsule realized that it was off course and self-destructed using a mechanism installed in part to ensure that the Americans could not recover the spacecraft in the event of a badly targeted re-entry.

The next Zond launch attempt w’as to have been a cireumlunar flight, but it failed ignominiously on April 22, 1968, when the spacecraft emergency escape system was erroneously triggered at the 194 second mark, shutting down the second stage of the launcher and carrying the Zond spacecraft clear. It was recovered 520 km from the pad. Another planned Zond launch w? ent awry on July 14, 1968. when the oxygen tank in the fourth stage ruptured on the pad during pre-launch testing, destroying the Block D stage and killing three engineers. Fortunately, the lower stages, all loaded with propellant, did not explode. Although undamaged, spacecraft 7K-L1 No.8 was discarded.

After this frustrating series of failures, Zond 5 became the first fully successful cireumlunar flight. Launched on September 14. 1968, it achieved its mission despite suffering several technical problems. The Earth sensor had been mounted incorrectly owing to an error in the documentation. The star-tracker attitude control system was rendered ineffective when its optical surfaces became contaminated by sublimating thermal protection material. Worse, the backup system was mistakenly turned off. But engineers were able to control the spacecraft’s attitude in an awkward and slow’ process using the Sun sensors. Two midcourse maneuvers were conducted, and the spacecraft flew7 around the Moon on September 18 with a closest point of approach at an altitude of 1,950 km. Jodrell Bank announced the achievement and reported the spacecraft heading back to Earth. Only at this point did the Soviets actually admit to having launched the mission! On the voyage home a second attitude control sensor failed. On September 21 the spacecraft re-entered at 11 km/s at an overly steep angle on a ballistic rather than the planned guided ‘skip’ re-emry. fortunately, after the loss of Zond 4, the self-destruction system had been deleted. After a 6 minuie ride through the atmosphere with peak stresses of 16 G and 13.000 C, the descent capsule parachuted into the Indian Ocean at 16:08 UT near 32.63’S 65.55’E. 105 km from the nearest Soviet tracking ship. This was the first water recovery for the Soviets. The eapsule was offloaded at Mumbai. India, for return lo Moscow by aircraft. This boosted Soviet confidence in their human lunar program, but the flight had suffered serious non-fatal failures.

Zond 6 was successfully launched on November 10. 1968. Attitude control again became a problem when the high gain antenna, with the main star tracker attached. Tailed to deploy. The backup siar tracker system and a lower gain antenna were used instead. As the spacecraft flew around the Moon on November 14 at an altitude of 2,420 km it photographed the near and far sides. On its way home engineers had to reorient the spacecraft to try to control the temperature in a hydrogen peroxide tank by exposing it to direct sunlight and unfortunately this also heated and deformed the hatch seal, causing the cabin to depressurize. The biology payload was killed and the altimeter damaged. In preparation for re-entry on November 17 the service module separated as intended but the high gain antenna remained attached to the front of the capsule. The vehicle entered the atmosphere at 11 km/s and after bleeding off some energy it skipped back into space at 7.6 km/s as intended, at which time the antenna detached. All went well with the ‘second dip’ until at an altitude of 5,300 meters the altimeter failed to function properly and commanded the parachute to be jettisoned. Some film was recovered from the wreckage, including the first color pictures of the Moon, before explosives engineers detonated the 10 kg of I N I that had been carried on board the capsule for the radio-command destruct system.

Of tw o circumlunar missions, Zond 5 had failed to perform the skip’ maneuver during re-entry and had made a ballistic descent and splashed into the Indian Ocean, and Zond 6 had flown the intended trajectory only to fail on its parachute within the Baikonur boundary only 16 km from the launch pad. Undeterred, the Soviets made a valiant effort to prepare a mission for the December opportunity. Cosmonauts in training for a circum lunar flight argued to be allowed to fly. A vehicle was rolled out to the pad on December 1. but the spacecraft suffered so many technical problems that the window closed before approval to launch could be obtained. Even after the successful flight of Apollo 8 later in the month, the Soviets continued with the Zond tests. The hardware was available and the obvious thing was to push for success and realize the benefits of the investment. There was no precedent for actually stopping a Soviet space project with this much visibility. There remained the hope of making a manned circumlunar flight, although this prospect faded as the focus switched to the N-l launcher.

But in the next 8 months, w hile the Americans reveled in the success of Apollo 8, 10 and 11. three more set backs were to plague the Soviet manned lunar program. Anxious to solve the problems with the Zonds, another test flight to lunar distance was planned before the circumlunar window’s opened in summer. The launch of 7K – L1 No. l3L failed in January 1969 due to problems with the second and third stages.

|

Figure 10.20 Proton launcher ready on the pad with Zond 5. |

One of four sccond-stagc engines shut down early, and then during its phase of the ascent the third stage suffered a breakdown in its fuel feed system and cut off. Even more significant for the manned program, in February and July of 1969 the first two test launches of the N-l lunar rocket also failed.

Nine months after the Zond 6 disaster, and shortly after Apollo 11 succeeded and the Soviet robotic lander Luna 15 crashed, Zond 7 was launched towards the Moon on August 7, 1969. The next day, it conducted a midcourse maneuver and took color pictures of Earth. On August 11 the spacecraft flew around the Moon at an altitude of 1,985 km and performed two sessions of color photography of both the Moon and Earth. It returned to Earth on August 14, made the intended ‘skipping’ re-entry and landed successfully in a preselected area south of Kustanai in Kazakhstan.

The plan had called for four test flights prior to a manned circumlunar mission, but of the four only Zond 5 and 7 wrere fully successful. This poor success rate led to

|

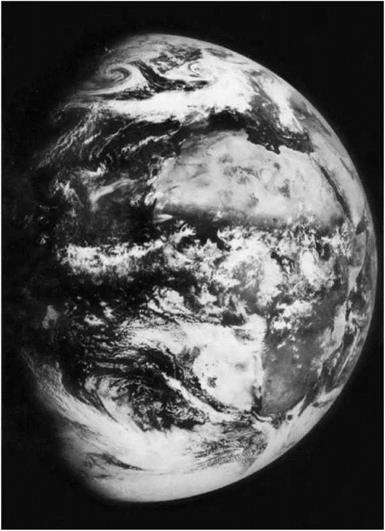

Figure 10.21 Picture of Earth from Zond 5. |

a proposal to fly one more test flight and then a manned mission to celebrate Lenin’s birthday in April 1970. The supporters argued that the flight would contribute to the program by demonstrating to the world that the USSR was capable of manned lunar missions. But the government rejected it because it would look second rate. To have sent cosmonauts on a circumlunar mission ahead of Apollo 8 would have been one thing, but to do so after Apollo 11 was something else. At the political level, benefit was now being determined relative to American achievements. Approval was given only for the final automated test flight.

Zond 8 vras launched on October 20, 1970. The next day it took pictures of Earth

|

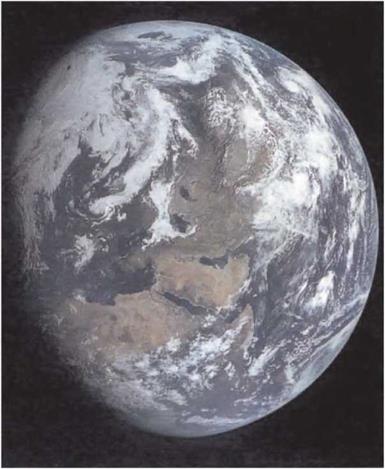

Figure 10.22 Photograph of the lunar surface and Earth from Zond 7. |

from 64,480 km, and the day after that it made a midcourse maneuver at a range of

250.0 km. ft transmitted images of Earth for 3 days during its outbound flight and conducted two imaging sessions as it passed behind the Moon on October 24 at an altitude of 1,110 km. After two midcourse correction maneuvers on the return leg, it made a ballistic re-entry over the northern hemisphere on a southbound trajectory to sustain communication in most of the re-entry sequence. All previous Zonds had reentered over the southern hemisphere, heading north. The capsule splashed into the Indian Ocean at 13:55 UT on October 27, approximately 24 km from the target point 730 km southeast of the Chagos Islands. It was recovered 15 minutes later by the Soviet oceanographic vessel Taman for return to Moscow by way of Bombay, India.

Results:

These were primarily engineering tesl flights, but they also carried payloads which provided scientific results.

Zond 5: High quality photographs of Earth were taken on the way home at a range of 90,000 km. They were useful because the film would be able to be processed on Earth rather than scanned on board and transmitted by radio. A biological payload of turtles, wine flies, fly eggs, meal worms, plants, seeds, bacteria, and other

|

Figure 10.23 Photograph of Earth from Zond 7. |

living matter was recovered. The turtles had lost significant body mass and exhibited other metabolic anomalies. The fly eggs had not produced the expected number of adults, and the next generations of these showed a large increase in mutations.

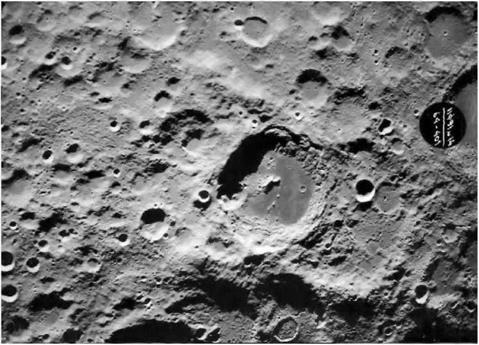

Zond 6: The crash broke the film canister, but some film was recovered including images of the lunar limb and far side features taken at ranges of approximately 3,300 to 11,000 km. Some stereo pairs were also obtained. Only a few of its images have been published.

Zond 7: Color photography of both Earth and the Moon. A biological payload of turtles, wine flics, meal worms, plants, seeds, bacteria, and other living matter was successfully recovered.

Zond 8: Obtained photographs of Earth and the Moon from distances of 9,500 and 1,500 km.

To sum up, although the photography was excellent the science results from these

|

Figure 10.24 Picture from Zond 8. |

test flights were minimal. Data on solar wind and cosmic rays was obtained but not published. The seed samples on recovered flights all showed chromosomal damage but of the animals only the turtles on Zond 5 showed any ill-effects.