THE PROTON LAUNCHER

The UR-500 Proton launcher was initially developed as an ICBM to carry heavier warheads over longer ranges than the R-7. By 1961 Vladimir Chelomey’s OKB-52 had developed a practical storable propellant fast-response ICBM for the military and Korolev’s R-7 had become a space launcher, so Khrushchev naturally enlisted Chelomey to build the larger rocket to deliver the new H-bomb. Chelomey’s answer was the Universal Rocket 500, or UR-500. However, as with fission devices, the Soviets soon learned how to make much lighter thermonuclear devices and the UR – 500 was canceled by the military. Chelomey convinced the government that his rocket, augmented with an upper stage, eould send cosmonauts on direct flights to the Moon for circumlunar missions. At that time, Korolev was envisaging achieving this by two launches and an Earth orbital rendezvous. Chelomey’s scheme would be simpler. lie succeeded in wresting the circumlunar project from OKB-1 and kept the UR-500 program alive with support from Keldysh, who wisely recognized that such a booster would have many important applications. In 1965 Korolev succeeded in regaining the spacecraft and fourth stage combination for the circumlunar project, his reasoning being that Chelomey had never built a spacecraft and OKB-1 already had one in production. The mission would use Chelomey’s booster but with the fifth stage from Korolev’s N-l rocket serving as its fourth stage. For use on the Proton stack, the N-l s Block D guidance package was removed and this function had to be provided by the spacecraft.

The three stages of the UR-500 were all powered by engines that burned nitrogen tetroxide and IJDMH. a combination despised by Korolev. The first stage had six highly advanced and very efficient closed-cycle RD-253 engines made by Korolev’s nemesis. Valentin Glushko in OKB-456. The second and third stages were powered by engines built by Kosberg s OKB-154. A feature of the first stage s design is that the UDMH is contained in six tanks arranged around the larger central oxidizer tank. This unique design was imposed by width limitations of the railway system, which precluded vehicle widths greater than 4.1 meters. The various tanks were therefore delivered separately and assembled at the launch site. A specialised rail transporter then took the completed vehicle to the pad.

The UR-500 began Hying only four years after being commissioned, and showed immediate promise with a two-stage version on July 16, 1965. successfully placing into orbit a very heavy Proton satellite to study cosmic rays; hence its popular name. The fifth launch on March 10, 1967. was the first for the four-stage IJR-500K. also know n as the Proton-K. This had Korolev s restartable Block D upper stage, w hich used his preferred propellants of kerosene and LOX. The payload w as the first in the

|

series of tests of the lunar Soyuz, disguised hy the name Zond, and was considered a success. The power of the Proton-K was irresistible for lunar and planetary missions, and it replaced the Molniya for lunar and Mars missions in 1969 and Venus missions in 1975. It became the workhorse for lunar and planetary missions in the 1970s and continued into the 1990s. Being much more powerful than the Molniya it facilitated much heavier and more sophisticated lunar and planetary spacecraft. Its lift capacity made possible such missions as lunar rovers, lunar sample returns, and soft landing missions on Mars and Venus. It was used for Zond 4 to 8, Luna 15 to 24, Mars 2 to 7, Venera 9 to 16, Vega 1 and 2, Phobos 1 and 2, and Mars-96. Several versions of the Block D fourth stage were developed for the Proton-K. The original was used for Luna 15 to 23, Zond 4 to 8, Mars 2 to 7 and Venera 9 and 10; the D-l version was used for Luna 24, Venera 11 to 16 and Vega 1 and 2; and the D-2 was employed for Phobos 1 and 2 and Mars-96. In all these missions, the spacecraft was required to supply guidance for the Block D stage.

One of the glaring reasons for so many failures in Luna, Zond, Venera and Mars missions in the late 60s and early 70s wns poor performance of the Proton vehicle. Succeeding in its initial launch and in two of its next three launches in 1965-66, its initial performance appeared promising. But its record in the 3 years from March 1967 to February 1970 was abysmal. Ten of nineteen spacecraft were lost w’hen the Proton failed to deliver the Block D to Earth orbit. Another three achieved orbit but were stranded when the second burn of the Block D failed. Only six of the nineteen launches were fully successful. Sixteen were interplanetary, and the Proton failed in eleven cases – four failures out of eight Zond launches to the Moon, five failures out of six Luna launches, and the failure of both Mars launches in 1969. Unfortunately, the failures were distributed throughout the vehicle including all stages, so it was very difficult to make the vehicle reliable.

NPO-Lavochkin was so concerned at the Proton failures that General Designer Gcorgi Babakin met with the Minister of General Machine Building in March 1970 to demand action. *Aftcr the rocket underwent a full engineering review a number of improvements were made, and the vehicle was re-qualificd in a successful test flight in August 1970. After this, the success record improved dramatically and eventually the Proton became one of the most reliable workhorses in the Soviet launcher fleet. Indeed, it today enjoys an excellent reputation and a large share of the commercial launch market.

|

Figure 4.7 Transport and erection of the Mars-96 Proton-K vehicle. |

|

N-l MOON ROCKET

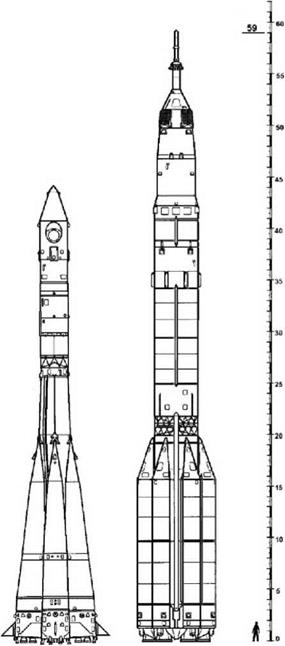

The N-l launcher was the Soviet counterpart to the Saturn V, and was developed for the same role. It had five stages, stood 105 meters tall, weighed 3,025 metric tons at launch and could place 95 metric tons in low Earth orbit. In contrast, the Saturn V

|

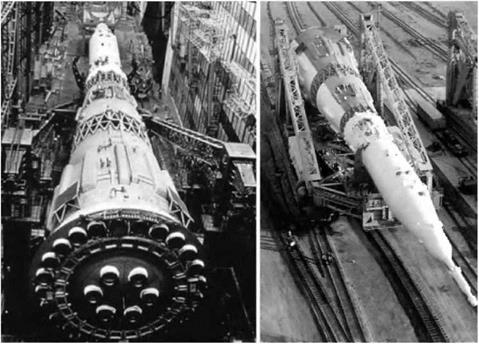

Figure 4.9 First N-l test vehicle in assembly (left) and on rollout (right). |

had four stages (treating the Apollo lunar module as equivalent to N-l’s fifth stage in the powered descent phase of the mission profile), stood 110 meters tall, weighed 3,0.19 metric tons at launch and could place 119 metric tons in low Earth orbit.

The first stage of the N-l had 30 NK-33 non-gimbaled 1.51 MN engines arranged in concentric rings with 24 around the outer ring and 6 around the inner. Large graphite vanes mounted on four of the outer ring engines provided thrust vectoring. If one of the engines malfunctioned, both it and the one diametrically opposite had to be shut down. The second stage had eight NK-43 1.76 MN engines, and the third stage had four NK-39 0.4 MN engines. The first three stages were to insert the fourth and fifth stages into low’ Earth orbit. At the appropriate time the fourth stage, powered by four NK-31 0.4 MN engines, would send the fifth stage, incorporating the orbiter/lander. towards the Moon. The LNK’ engines were made by OKB-276, headed by Nikolai Dmitriyevich Kuznetsov, and used a LOX-kerosene combination. The fifth stage was the Block D which Korolev adapted to serve as the fourth stage of the Proton-K. It was powered by a single Melnikov RD-58 engine that also used LOX-kerosene, and was to perform midcourse maneuvers, lunar orbit insertion and the majority of the powered descent, being discarded in the final phase to enable the lander to use its own engine to perform the soft landing.

The N-l failed test flights in February and July of 1969, in the latter case with a spectacular explosion at liftoff that dashed Soviet hopes of competing with the US Apollo program. The N-1 had another test flight in 1971 and a final test in 1972. The

|

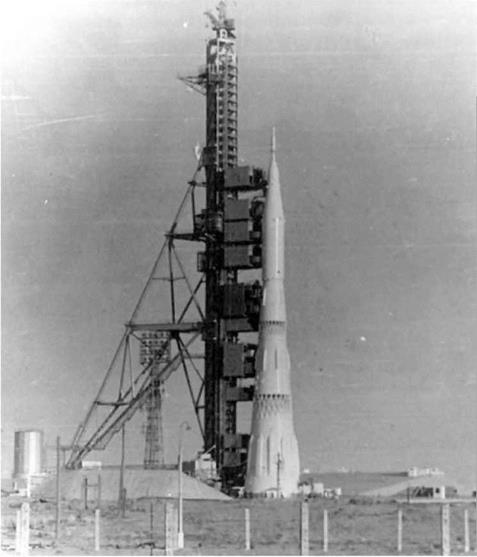

Figure 4.10 N-l oil the pud just prior to hituieh. |

first stage failed each time and the project was abandoned. Its Achilles’ heel was the large number of engines that all had to work without adversely affecting the others. Remarkably, there were no static test firings. The launch attempts in 1969 carried an automated form of the Soyuz 7K-LI drcumlnnar spacecraft and a dummy LK lunar lander. The launches in 1972 carried an automated Soyuz 7K-LOK lunar orbiter and dummy LK lunar lander. The only successful result was proof that the escape rocket could pull the crew module clear of the exploding rocket.