IN LUNAR ORBIT

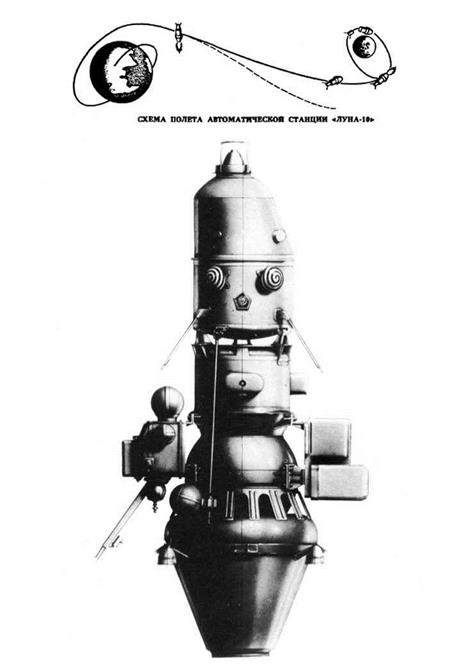

Having achieved the first delivery of a scientific capsule to the lunar surface, the Soviets moved on to attempt to be first to put a satellite into orbit around the Moon. Luna 10 was launched at 10:47 GMT on 31 March 1966. After cruising in parking orbit, it set off for the Moon. It was the same type of bus as Luna 9, but was ferrying an instrument capsule instead of the landing capsule. The midcourse manoeuvre on 1 April refined the trajectory to aim for the point in space at which the 850-m/s orbit insertion burn would be made. When 8,000 km out, it oriented itself for braking. The burn was initiated at 18:44 on 3 April, and slowed the spacecraft sufficiently for it to enter a 350 x 1,017-km orbit with a period of 178 minutes, in a plane inclined at 72 degrees to the lunar equator. The fact that the change in velocity to enter orbit was considerably less than that to land meant that propellant could be traded in favour of an increase in the payload to 245 kg. Shortly after entering orbit the bus released the 1.5-metre-long capsule containing a micrometeoroid detector, radiation detectors, an infrared sensor to measure the heat flux from the Moon, a gamma – ray spectrometer to detect radioactive isotopes, and a magnetometer to follow up the measurements by the early flyby probes. The mission ended when the battery expired on 30 May, after 56 days during which the capsule made 460 revolutions.

|

|

|

In lunar orbit |

|

141 |

The gamma-ray spectrometer was similar to that of the Ranger Block II, but more useful by virtue of being placed into orbit to survey a wide area. The instrument was a scintillation spectrometer with a resolution of 32 channels within the energy range 0.3-3.0 MeV. The surface resolution was rudimentary. The data was consistent with the proposition that the maria were basaltic, but was inconclusive. About the only positive conclusion was there were no large surface exposures of acidic rock such as granite. The question for the ‘hot Moon’ hypothesis advocated by Gerard Kuiper, was why the process which produced ‘continental’ material on Earth had seemingly not done so on the Moon. The mystery was the composition of the highland material. If a global magnetic field existed, then it was weaker than 1/100,000th that of Earth. Radio occultations on crossing the limb showed no hint of the Moon having even a tenuous envelope of gas. Intriguingly, radio tracking revealed the gravitational field to be uneven.