ON THE SURFACE

The Soviet effort to deliver a capsule to the lunar surface using the rough landing technique finally succeeded with Luna 9. This was launched at 11:42 GMT on 31 January 1966. Its mass was 1,538 kg, including the surface capsule. The midcourse manoeuvre was made at 19:29 on 1 February. As with the Block II Ranger, the inability to deal with a lateral velocity component in the descent limited targets to longitudes of about 64°W and fairly near the equator. In this case, the target was in Oceanus Procellarum, near Hevelius. At an altitude of 8,300 km, with about half an hour to go, the spacecraft aligned its main axis to local vertical. The radar altimeter initiated the retro manoeuvre at 18:44:42 on 3 February, at an altitude of 75 km. At 18:45:30, after slowing by 2.6 km/sec, the engine was cut off when a 5-metre-long probe made contact with the surface, and simultaneously the payload was ejected upward and to the side. The bus hit the ground at 6 m/s and its transmission ceased.

The 250-foot-diameter radio dish at Jodrell Bank in England was the largest fully steerable antenna in the world, and it was monitoring the transmission. When the signal ceased, Bernard Lovell, the head of the facility, wrote it off as another failed landing. But the shock-proof 58-cm-diameter spheroidal capsule rolled to a halt and, some 250 seconds after being released, initiated its own transmission. Four petals opened to right and stabilise the capsule and to expose its contents, which comprised a radiation detector and a line-scan TV camera that pointed upward and viewed the landscape using a nodding mirror that could rotate in azimuth.

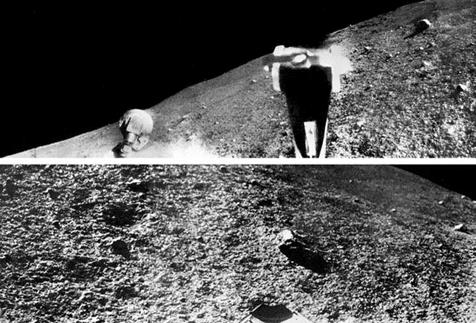

Between 01:50 and 03:37 on 4 February a panoramic picture was built up line by line and the data transmitted in real-time. Jodrell Bank recorded the transmission. On a hunch, Bernard Lovell asked the local office of the Daily Express to provide a commercial wire-facsimile machine, and the signal was fed into it. Even before the Soviets announced their probe had transmitted a picture, the ‘scoop’ was published in Britain with the headline: From Luna 9 to Manchester – The Express Catches the Moon. Unfortunately, not knowing how to extract the aspect ratio of the image from the telemetry, they had guessed, and caused the horizontal scale to be compressed by a factor of 2.5, and since it was consistent with the popular expectation of the lunar surface, the resulting jagged landscape seemed ‘right’. The ruggedness was further emphasised by the fact that the Sun was just 7 degrees above the horizon and cast very long, very dark shadows. The surface looked like glassy scoriaceous lava that would be very treacherous for an astronaut to walk on – much like the ‘aa’ lava in Hawaii, so named because a person walking on it tends to cry that sound!

When the official version was issued later using the true aspect ratio, the jagged ‘spikes’ were seen to be just rocks resting on the surface, and the scene was rather less dramatic. The capsule had come to rest oriented 16.5 degrees off vertical. The field of view spanned 11 degrees above and 18 degrees below the perpendicular to the capsule’s axis, with a series of 6,000 vertical lines spanning a full 360 degrees of

|

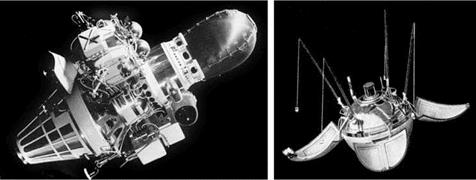

A model of the Luna 9 spacecraft showing the spheroidal surface capsule attached to the bus, and (right) the capsule in its deployed configuration. The camera is the cylindrical unit on the axis. |

|

Two sections of a panoramic image transmitted by Luna 9. (Courtesy of Philip J. Stooke, adapted from International Atlas of Lunar Exploration, 2007) |

azimuth. As the mirror was only 60 cm off the ground, the perspective was very low, with objects in the foreground appearing larger than they were, and the horizon was very close as a result of the capsule having landed in a shallow 25-metre-diameter crater. There was no sign of the bus.

Gerard Kuiper claimed that there were vesicles in the rocks, which supported his idea that the maria were volcanic. As meteors were particles of dust that penetrated

the Earth’s atmosphere, it seemed only reasonable that the airless Moon would have accumulated a blanket of such material, but this did not seem to be the case. Thomas Gold responded to the evident absence of dust (on this patch of mare, where it could reasonably have been expected to be very thick) by suggesting that the ‘rocks’ were not fragments of lava but fine powder which had adhered to form clods. The surface clearly had sufficient bearing strength to support the capsule’s 100-kg mass – but in the weak lunar gravity its weight was one sixth of this value. To the Apollo planners, this was the most significant result of the mission. Gold argued that the capsule was spreading this load across the four deployed panels, and in time it would sink from sight. The geologists of the Branch of Astrogeology inferred that the surface was (to use Harold Urey’s term) gardened by impacts. The site was on a dark geological unit that Jack McCauley, in making the Lunar Astronautical Chart for this area, had interpreted as a pyroclastic blanket with lava flows. Although there was nothing in the image to suggest pyroclastic, it did indeed look like a lava flow, and judging by the sharpness of the rocks and the absence of dust it was relatively young in terms of lunar history.

A second panorama was taken between 14:00 and 16:54 on 4 February, and this showed that the capsule had increased its tilt to an angle of 22.5 degrees, altering the angle of the horizon. Gold claimed this was evidence of the capsule sinking into the dust. The offset had the benefit of facilitating limited stereoscopic analysis. Before the battery expired on 6 February, further partial pans were made to observe how the illumination changed as the elevation of the Sun in the lunar sky increased, thereby demonstrating the value of repeatedly imaging a scene from a fixed vantage point.