REPEAT PERFORMANCE

Now that Ranger Block III had proved itself, the Office of Manned Space Flight asserted its right to specify the requirements for future targets. On 16 October 1964 Sam Phillips, the Apollo Program Director, told Oran Nicks that Ranger 8 should investigate a mare plain in the Apollo zone at a position which was not crossed by rays. At a meeting at JPL on 19 November, the scientists argued for comparing the ‘reddish’ Mare Nubium with a ‘bluish’ one in the eastern hemisphere. Nicks made the formal recommendation to Homer Newell on 9 February 1965, who concurred. The target for the first day of the launch window was to be Mare Tranquillitatis, but if the launch were delayed then it would move westward along the Apollo zone to keep pace with the migrating terminator. The launch window for Ranger 8 opened on 17 February. The Moon was ‘full’ on 16 February and would be ‘last quarter’ on 23 February.

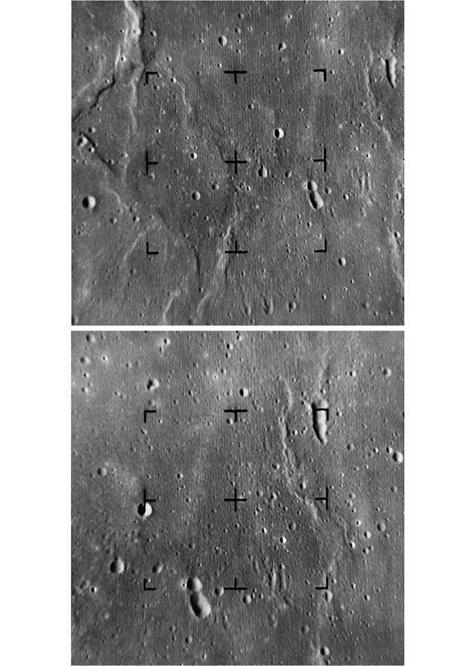

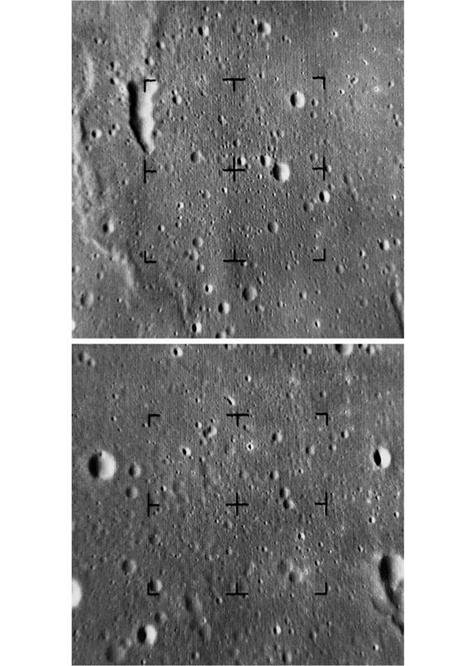

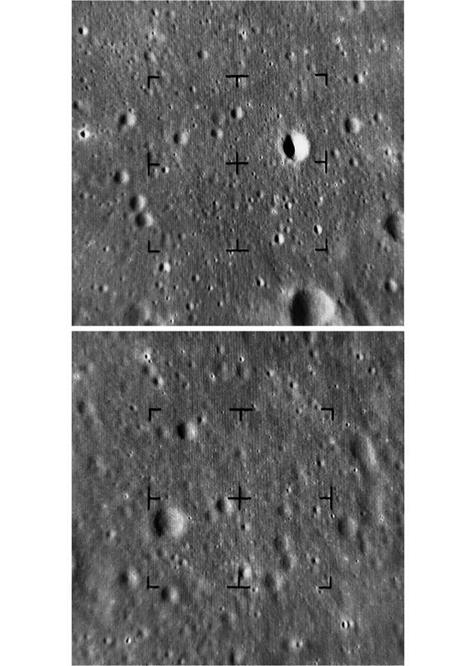

Launch was at 17:05 GMT on 17 February. The translunar injection produced a flyby at a range of 1,828 km. The trajectory was refined by a 59-second midcourse manoeuvre at 10:27 on 18 February. When Ranger 8 made its approach to the Moon, it was decided to start the cameras several minutes early so that the initial pictures would be comparable to the best attainable by a terrestrial telescope. A total of 7,137 pictures were received – almost twice as many as from Ranger 7 owing to the extended sequence. Whereas Ranger 7 had made a near-vertical descent west of the meridian, the target for Ranger 8 was 24 degrees east of the meridian and to reach it the spacecraft had to make a slanting approach. Whilst this significantly increased the areal coverage, in particular depicting the central highlands at an unprecedented resolution, it meant there was no overlap between the frames later on and the lateral velocity smeared the final frames. The impact occurred at 09:57:38 on 20 February. Don Wilhelms was watching through the 36-inch refractor at the Lick Observatory near San Jose in California and listening to a radio countdown from JPL, but saw no flash. Alika Herring of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory was using the 84-inch reflector at the Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona, but did not see anything either. As a result of the lack of overlap, the impact point was not actually within the final frame – not that it really mattered, it was calculated from the trajectory as being 24 km from the aim point.[23] In this case, owing to the smearing of the final images, the best resolution was 1.5 metres.

At a press conference 30 minutes later given by W. H. Pickering, Edgar Cortright, William Cunningham and Harris Schurmeier, the latter delightedly summed up the mission as “another textbook flight”.

The experimenters presented some of the pictures later in the day. There were more rocks than at the Mare Nubium site, once again indicating a substantial bearing strength. In fact, this area was one of the ‘hot spots’ in near-infrared measurements made during the lunar eclipse of 19 December 1964, and the exposed rock supported the interpretation of such thermal anomalies as being due to rocks slowly radiating their heat when the Moon entered into the Earth’s shadow.

Despite the intention to investigate a mare site free of rays, it was discovered that Ranger 8 came down over a faint ray from Theophilus. One striking observation was that the surface of Mare Tranquillitatis appeared remarkably similar to that of Mare Nubium. In fact, Gerard Kuiper, showing one of the final frames, remarked, ‘‘If you didn’t know that this was taken by Ranger 8, you’d think it was one of the Ranger 7 pictures.’’ It was ventured that ‘‘probably all lunar maria are pretty much this way’’.

Harold Urey introduced the term ‘dimple crater’ for irregular rimless pits which, it was speculated, might be where loose surficial material had drained into a cavity in much the same way as sand drains in an hourglass. Noting that tubes and cavities occur in terrestrial lava fields, and believing the lunar maria to be lava flows, Kuiper speculated that such pits might pose a ‘‘treacherous’’ threat to an Apollo lander. To Gene Shoemaker, however, they appeared merely to be degraded secondary impact craters.

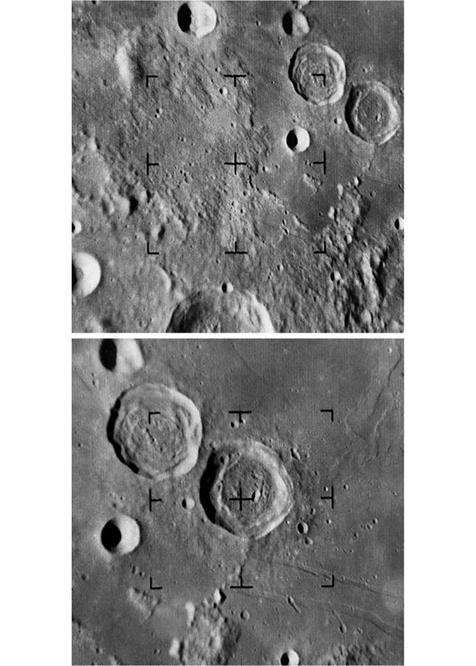

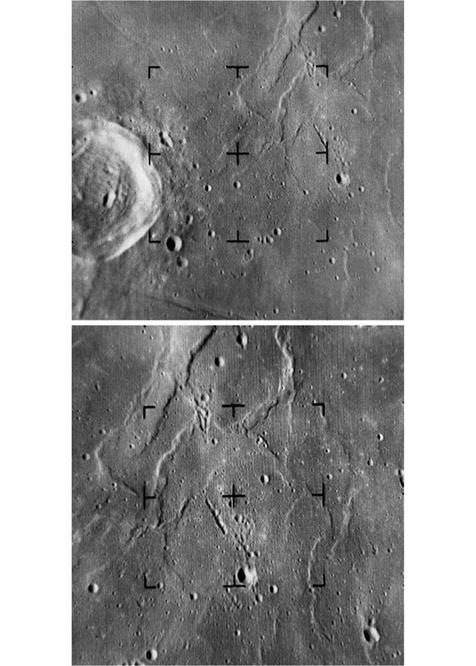

On the larger scale, the scientists were pleased that as Ranger 8 made its slanting approach it provided views of Ritter and Sabine in unprecedented detail. These two 30-km-diameter craters in the southwestern Mare Tranquillitatis lacked radial ejecta and secondary craters, and their depth-to-diameter ratios made them anomalously shallow in terms of the curve plotted for impacts by Ralph Baldwin. The fact that they were aligned along the Hypatia rilles, were located on the fringe of a mare and had ‘raised floors’ had led some people to interpret them as volcanic calderas. Even people who favoured the impact origin of craters allowed that Ritter and Sabine

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

might be ‘hybrid craters’ that were excavated by impacts and later modified by volcanism stimulated by their formation – indeed, they were the exemplars of this hypothesis.