Ranger struggles

STRANDED

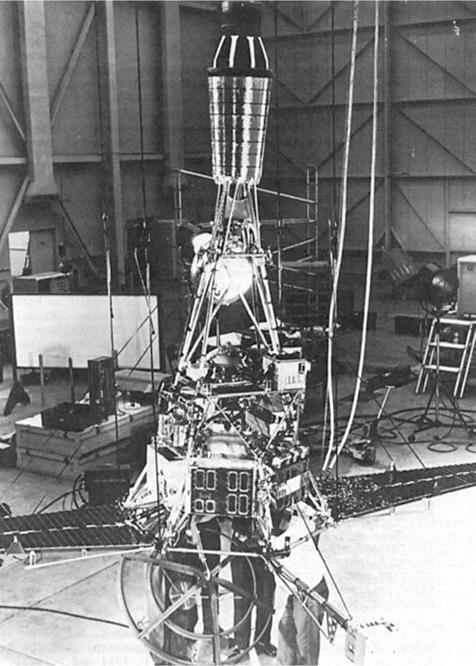

After Ranger 1 passed its qualification tests at JPL in May 1961, Oran Nicks, Chief of Lunar Flight Systems at NASA headquarters, authorised its transportation to Cape Canaveral, where the Air Force had assigned Hangar AE to the project. The launch window ran from 26 July to 2 August. In late June the Atlas was erected on Pad 12, the Agena added, and the spacecraft in its aerodynamic shroud installed to complete the stack. The combined systems tests of the fully assembled space vehicle were concluded on 13 July.

The countdown was delayed three days by a variety of problems, and was unable to start until the evening of 28 July with the intention of launching at dawn the next day, but a problem with the Cape’s electrical power supply meant that the clock had to be halted with 28 minutes remaining. After two other counts were frustrated, the attempt to launch on 2 August was abandoned when, as high voltage was applied to the spacecraft’s scientific instruments for calibration purposes, an electrical failure caused the explosive bolts to fire to deploy the solar panels inside the shroud. The spacecraft had to be retrieved and returned to the hangar. It was concluded that there had been an electrical arc to the spacecraft’s frame, but the precise source was not evident. The damaged parts were replaced. The launch was rescheduled for the start of the window for the next lunation.

The countdown began on the evening of 22 August and ran smoothly to liftoff at 10:04:10 GMT the next morning. With Ranger 1 on its way, James Burke became Mission Director at the Hangar AE command post.

The Atlas ignited its sustainer, the two side-mounted boosters and the two vernier control engines, and was held on the pad until verified to be running satisfactorily. For the first 2 seconds the vehicle rose vertically, and then it rolled for 13 seconds to swing its guidance system onto the flight azimuth. After 15 seconds the autopilot pitched the vehicle in that direction so as to arc out over the Atlantic. When a sensor detected that the acceleration had reached 5.7 times that of

Earth gravity,[20] about 142 seconds into the flight, the Atlas shut off its boosters, and 3 seconds later jettisoned its tail to shed 6,000 pounds of ‘dead weight’. The sustainer engine continued to fire. In the boost phase, the vehicle had been tracked by a radar at the Cape to enable the Air Force to calculate its initial trajectory, and as the sustainer flew on it acted upon steering commands radioed by the ground. When the sustainer shut down, the two verniers on the side of the Atlas fired as appropriate to refine the final velocity. As it did not have the power to insert the Agena directly into orbit, the upper stage was to be released on a high ballistic arc. Once free, the Agena, now above the dense lower atmosphere, jettisoned the aerodynamic shroud to shed dead weight, and ignited its engine. ft then achieved the desired circular parking orbit at an altitude of 160 km. Meanwhile, the Air Force’s computer processed the tracking provided by the radars of the downrange stations of the Eastern Test Range in order to calculate the length of time the Agena should spend in parking orbit and the parameters required for its second manoeuvre. This information was transmitted to the vehicle.

The plan for this test flight was for the Agena В to use its second burn to enter an elliptical orbit with an apogee of 1 million km, far beyond the orbit of the Moon, and for simplicity the orbit would be oriented not to venture near the Moon. The primary objective was to evaluate the spacecraft’s systems in the deep-space environment, in particular its 3-axis stabilisation using Earth, Sun and star sensors, the pointing of its high-gain antenna, and the performance of the solar panels. Each Block f Ranger was expected to have an operating life of several months, and to provide worthwhile data for the sky scientists.

After its second burn, the Agena was to fire explosive bolts in order to release the spacecraft, which would be pushed away by springs. Then the spent stage was to use its thrusters to make its trajectory diverge. Radio interference prevented the tracking site at Ascension fsland in the South Atlantic from monitoring the reignition. When Johannesburg reported detecting the spacecraft several minutes ahead of schedule, it became evident that the second burn had failed and the spacecraft was still in a low orbit. When Goldstone picked it up, the orbit was calculated to have a perigee of 168 km and an apogee of 500 km. Although the Agena had reignited, it had shut down prematurely and then released the spacecraft. ft was encouraging that the spacecraft had deployed its solar panels, locked onto the Sun, rolled to acquire Earth and then deployed its antenna, but because it was ‘stranded’ in a low orbit it soon entered the Earth’s shadow and lost both power and attitude lock. On re-emerging into sunlight it fired its thrusters to restabilise itself. This occurred on every shadow passage, with the result that after only one day the nitrogen was exhausted and, unable to stabilise itself to face its solar panels to the Sun, the battery, intended only for launch and the brief midcourse manoeuvre, expired. The inert spacecraft re-entered the atmosphere on 30 August.

A study of the telemetry tapes confirmed that the Agena reignition sequence had started at the proper time, but almost immediately the flow of oxidiser had ceased. The small amount of oxidiser which had entered the engine gave the 70-m/s velocity

|

|

|

increment that slightly raised the apogee. The premature cutoff was classified as a one-off failure.

Although Ranger 1 flew in an environment different to that intended, its designers were encouraged that it had correctly deployed its appendages and (repeatedly) been able to adopt cruise attitude. But the sky scientists received nothing of value from the mission.

On 5 October, as a result of lessons learned from Ranger 1 when various lines of authority had penetrated the Space Flight Operations Center, Marshall Johnson was appointed Chief of the Space Flight Operations Section and, with it, sole authority to direct the control team while a mission was underway.

The launch window for Ranger 2 was 20-28 October 1961. The tests on the fully assembled space vehicle on Pad 12 were completed on 11 October. The countdown began on time in the evening of 19 October, but was scrubbed with 40 minutes on the clock owing to a fault with the Atlas. Although this was readily repaired, the fact that another Atlas was due to leave from another pad the next day meant Ranger 2 had to wait. The countdown on 23 October was abandoned because of another issue with the Atlas. At this point, a Thor-Agena B launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California was lost as a result of the failure of the hydraulics of the Agena’s engine, and NASA decided to await the outcome of that investigation. The problem was diagnosed and fixed in time for the next window, and Ranger 2 lifted off on the first attempt at 08:12 GMT on 18 November. As before, the spacecraft rose above the horizon at Johannesburg early, indicating that the second burn had failed – this time without even producing a modest apogee. Ranger 2 performed perfectly, but it was doomed and re-entered the atmosphere on 19 November.

An Air Force analysis of the telemetry indicated that the roll gyroscope of the Agena B’s guidance system had been inoperative at liftoff, most probably due to a faulty relay in its power supply. The attitude control system had compensated for the roll control failure by using its thrusters, and in so doing had exhausted the supply of gas. As a result, the Agena had tumbled in parking orbit. This caused the propellants to slosh in their tanks, which in turn prevented them from flowing into the engine when it tried to reignite. On 4 December 1961 the Air Force informed NASA of its findings, and Lockheed promised to report within a month on how it would fix the fault. When NASA decided in December 1959 to use the Agena B, it had presumed the Air Force would have worked the bugs out of the vehicle by the time it was needed, but only one had been launched prior to Ranger 1 and, in effect, NASA was testing it for the Air Force!

Although some aspects of the Block I tests had not been achieved, the engineers at JPL were encouraged that on both occasions the spacecraft had worked as well as could be expected in the circumstances. If the Agena was fixed as soon as Lockheed hoped, then it should be possible to proceed with Ranger 3 as planned.