MORE SOVIET SUCCESSES

Luna 2 was launched at 06:40 GMT on 12 September 1959, and 33.5 hours later it smashed into the Moon in the triangle defined by the craters Archimedes, Aristillus and Autolycus. On striking the ground at 3 km/sec, the probe would have vaporised. It carried similar instruments to its predecessor. In extending the particles and fields survey down to the surface, it found no appreciable magnetic field and no evidence of a radiation belt. The Earth’s field is generated by electric currents in molten iron in the core. The absence of a dipole field suggested that either the Moon had never developed a molten core, or it had and either the rate of the Moon’s rotation was too slow to generate electric currents or the core had since solidified.9

When Luna 3 was launched at 00:44 GMT on 4 October 1959, it was to undertake the eagerly anticipated photographic mission. It was inserted into a highly eccentric orbit of Earth which would provide a view of the far-side of the Moon. The 279-kg probe was 1.3 metres long. The main body was a 1.2-metre-diameter cylinder, and it had solar transducer cells in fixed positions on its exterior. The earlier probes in this series were battery powered, but a battery would not provide the duration required to undertake this particular mission. In addition to particles and fields instruments, the probe had a camera. Its trajectory crossed the radius of the Moon’s orbit 6,200 km to the south of the Moon. The point of closest approach was at 14:16 on 6 October, and lunar gravity deflected the trajectory northward. While coasting, the probe was spin stabilised. On approaching the Earth-Moon plane, beyond the Moon, gas jets halted the spin, a Sun sensor locked on, and the vehicle rolled until another sensor enabled the optics to view the Moon.

The camera had a 200-mm f/5.6 lens and a 500-mm f/9.6 narrow-angle lens, with the optical axes coaligned. Starting at 03:30 on 7 October, at a range of 65,200 km, pairs of pictures were captured simultaneously on 35-mm film which had a ‘slow’ rating in order to resist being ‘fogged’ by the radiation in the space environment. After 40 minutes of photography, the vehicle resumed its spin for stability. The film was wet-developed, fixed and dried. After the probe had achieved the 480,000-km apogee on 10 October, it headed back for the 47,500-km perigee on 18 October. The film was scanned using a constant-brightness light beam which was detected by a photoelectric multiplier whose output took the form of an analogue signal. The scanner had two transmission rates: a slow rate for when far away from Earth and a higher rate for perigee. Contact with the probe was lost on 22 October. On Earth, the signal was recorded on magnetic tape for further processing. The raw images were marred by bands of ‘noise’, which had to be ‘removed’, and the contrast was drawn

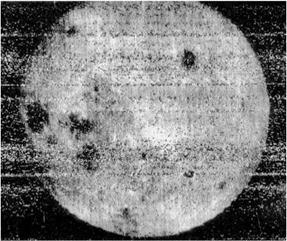

A picture taken by Luna 3 on 7 October 1959 showing Mare Crisium (on the left) and a large portion of the hitherto unobserved hemisphere of the Moon.

out to emphasise detail. In the wide lens the lunar disk spanned 10 mm, and in the narrow lens it was 25 mm.

out to emphasise detail. In the wide lens the lunar disk spanned 10 mm, and in the narrow lens it was 25 mm.

The phase of the Moon was ‘new’ on 2 October and ‘first quarter’ on 9 October. Therefore, when the pictures were taken on 7 October a portion of the near-side was illuminated. The prominent presence of Mare Crisium gave a sense of perspective. The remainder of the illuminated zone was 70 per cent of the hitherto unobserved region. As the Sun was directly behind the camera, the lack of shadow detail made it impossible to discern the topography. However, the results did show there to be few dark features – revealing the hemispheres which faced towards and away from Earth to be different. The maria cover 30 per cent of the near-side, but only 2 per cent of the far-side; in total about 16 per cent. The likelihood of there being fewer maria had been inferred from the paucity of maria on the limb, with those present being patchy rather than major plains, but their virtual absence was a surprise. The fact that the Moon’s rotation is ‘tidally locked’ with Earth was evidently an important factor in creating the dichotomy between the two hemispheres.

The results were published in 1960 as Atlas Obratnoy Storony Luny by N. P. Barabashov, A. A. Mikhaylov and Yu. N. Lipskiy. They unilaterally assigned names to the far-side features, with the two most prominent dark patches becoming Mare Moscoviense and Tsiolkovsky.[10] The atlas listed some 500 features of various types on a scale which represented the Moon as a disk 35 cm in diameter.

The Luna 3 mission was a remarkable success for the first attempt at a difficult task.