Geologists’ Moon

EARLY IDEAS ABOUT LUNAR CRATERS

In 1662 Robert Hooke was made curator of the recently formed Royal Society of London. He was charged with devising demonstration experiments. As an extremely skilled technical artist, in 1665 he published Micrographica, which was profusely illustrated with his own observations using a telescope and a microscope. Although he included a detailed drawing of the lunar crater Hipparchus, which is at the centre of the Moon’s disk, he had no desire to map the Moon. However, he undertook a series of experiments to investigate how craters may have formed. First he dropped heavy balls into tightly packed wet clay, and examined the imprints that they made. He also heated alabaster until it bubbled, and then let it set so that the last bubbles to break the surface produced craters. However, just as Hooke could not imagine where the projectiles could have come from to scar the Moon so intensively, nor could he conceive how the surface could have been sufficiently hot to blister on such a scale.

Following the discovery of the first two asteroids in 1801 and 1802, Marshal von Bieberstein in Germany suggested that lunar craters were created by the impact of such bodies. This was reiterated independently in 1815 by Karl Ehrenbert von Moll. In 1829 Franz von Gruithuisen agreed. However, the idea was rejected by those who supported the anti-catastrophist paradigm of uniformitarianism in terrestrial geology which was developed in the 1830s and 1840s.[4] In 1873 Richard A. Proctor published The Moon. Although this book was largely devoted to the motions of the Moon, he revived the idea that the craters marked impacts. But when the second edition of the book was issued in 1878 this section had been deleted. What puzzled the nineteenth century proponents of the impact hypothesis was that the lunar

|

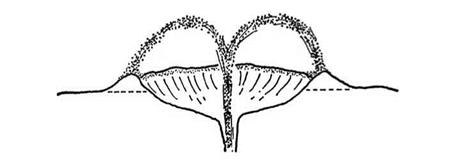

In 1874 James Nasmyth and James Carpenter proposed that volcanic ‘fountains’ produced the lunar craters. (Courtesy Patrick Moore, Survey of the Moon, 1963) |

craters are almost all circular, whereas the majority of bodies must have struck at an oblique angle and, it was presumed, produced elliptical craters.

In 1874 James Nasmyth and James Carpenter in England published The Moon, in which they attempted to explain how the surface features may have formed. As had Hooke two centuries earlier, they made model craters in experiments. They came to the conclusion that the lunar craters were produced by ‘fountains’ of material. In the early part of an eruption, when the velocity of the material ejected from the vent was great, the material would spray out in an umbrella-shaped plume and fall back some distance away to build up a concentric ring that became the wall of the crater. In many cases, as the eruption declined the fallout formed a succession of terraces interior to the wall. They presumed that in some cases the final phase of the eruption either built up the central peak, or in the case of craters with dark floors and no peak, switched to fluid lava that was confined to the cavity and buried the vent. In view of the weak gravity and absence of an atmosphere, it seemed plausible that this process could have produced very large structures.

Other explanations were offered for the origin of lunar craters. In 1854 the Danish astronomer Peter Andreas Hansen argued that the Moon bulged towards Earth, that its centre of gravity was displaced 50 km towards the far-side, and that this had drawn all the air and water on the surface around to the far-side, to where the inhabitants had relocated. In 1917 D. P. Beard suggested that the Moon was once immersed in a deep ocean, that the craters were limestone structures similar to coral reefs, and they were left exposed when the water flowed to the far-side.