EARLY TELESCOPIC IMPRESSIONS OF THE MOON

In 1600 William Gilbert, one of Queen Elizabeth I’s physicians and a keen natural philosopher, published the book De Magnete in which he proposed that the planets circled the Sun as a result of some attractive force – and as his great interest was the Earth’s magnetic field he suggested that this force was magnetism. In regard to the Moon, Gilbert shared Leonardo Da Vinci’s view that the bright areas were seas, and after making a sketch of the face of the Moon he assigned names to the dark areas. The drawing was not published until 1651, long after his death.

Hans Lippershey was born in Germany in 1570, but became a citizen of Flemish Zeeland in 1602 and lived in Middleberg, earning his living as a spectacle maker. He is usually credited with discovering in 1608 that using lenses in combination could provide a magnified view of a remote object, but such instruments were apparently developed several times in different places in preceding decades – the telescope was evidently a device whose time had come. On 2 October 1608 Lippershey applied to The Hague for a patent. Several weeks later so did optical instrument maker, Jacob Metius. Both applications were refused. After an account of Lippershey’s telescope was included in a widely circulated diplomatic dispatch, there was a proliferation of telescopes across Europe.

|

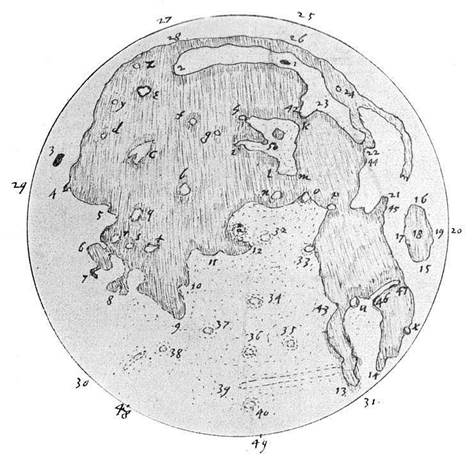

Thomas Harriot began to study the Moon telescopically in the summer of 1609 and in 1611 compiled a map based on his observations. |

Thomas Harriot graduated in mathematics from Oxford in England. He tutored Sir Walter Raleigh on navigational issues, in particular the ‘longitude problem’, and on several occasions sailed with him. By 1603 Harriot was wealthy, living in London and pursuing his interest in optics. The appearance of a comet in 1607 prompted his interest in astronomy. In 1608 he obtained from Holland a crude telescope that had a magnification factor of six, and on 26 July 1609 aimed it at the Moon and sketched what he saw. After further observations, in 1611 he compiled a whole-disk map. His work was never published, and it remained unknown until discovered in 1965 by E. Strout of the Institute of the History of Science in the Soviet Union.

Galileo Galilei was born in 1564 in Pisa in Tuscany. He was a mathematician and experimentalist. In 1589 he was made professor of mathematics at the University of Pisa, but three years later took a similar position at the University of Padua. During a visit to Venice in July 1609 he heard of the invention of the telescope via a letter written to one of his friends by a French nobleman. Galileo promptly set out to make one. Whereas Lippershey had used two convex lenses, Galileo combined a convex lens with a concave one to obtain an upright image. It had a magnification factor of ten. On 25 August he displayed it to the Venetian Senate, pointing out that it would enable an inbound ship to be identified several hours earlier than would otherwise be possible – knowledge which would be commercially valuable in a city of merchants. He was rewarded with an increase in salary. In October he went to Florence to show the telescope to his former pupil, Cosimo de Medici, now Grand Duke of Florence. On returning to Padua, Galileo made one with double the magnification factor. On 30 November turned this to the Moon, and again five times over the next 18 nights as the illumination phase changed. As he had a leaning towards painting, his depictions of what he saw were more representational than technical – with the result that few of the features he drew are recognisable. He never drew a full disk to consolidate his observations. After this burst of activity, he seems to have paid little attention to the Moon – but, to be fair, he was busy making discoveries about other celestial bodies. He wrote an account of his observations in the pamphlet Sidereus Nuncius, which he dedicated to de Medici and published on 12 March 1610.

Of the ‘imperfections’ on the Moon he wrote, ‘‘We could perceive that the surface of the Moon is neither smooth nor uniform, nor accurately spherical, […] but that it is uneven, rough, replete with cavities and packed with protruding eminences, in no other wise than the Earth, which is also characterised by mountains and valleys.’’ He was particularly struck by the shadows, which appeared totally black – there was no detail evident within them. He used the shadows cast by mountains to estimate their heights.[1]

But Galileo’s most significant discovery was that Venus displays phases similar to

|

Representations of the Moon at two illumination phases made by Galileo Galilei in late 1609 and published in 1610. |

the Moon, which was proof that this planet orbits the Sun, not Earth. Although the Church was not overly concerned about imperfections on the Moon, it was firmly of the belief that Aristotle was correct in saying that Earth was located at the centre of a system of crystal spheres. However, the phases of Venus meant that Copernicus was correct, which was a serious matter. After being hounded by the Roman Inquisition, in 1633 Galileo was obliged to publicly “curse and detest” the false opinion that the Sun held the central position. He was then placed under house arrest, and that is how he lived until his death in 1642.

Although Galileo may not have been the first to aim a telescope at the heavens, he was the first to publish, and the rapid distribution of his pamphlet prompted a great many people to obtain instruments to look for themselves.

Francesco Fontana, a Neapolitan lawyer, began to observe the Moon in 1630, and in 1646 published Novae Coelestium, Terrestriumque Rerum Observationes, featuring wood-cut engravings of two of his drawings made at different illumination phases.

Although Kepler knew that Galileo’s findings confirmed the Sun to be centrally located, he was wary of saying so explicitly. Since the Moon was evidently a world in its own right, he wrote an allegorical fantasy, Somnium, in which he related how ‘demons’ transferred his hero character to the Moon at the time of a lunar eclipse by sending him down the Earth’s shadow. The fact that the explanatory footnotes were longer than the text of the story established it to be a technical treatise disguised as a work of fiction. Even so, it was not published until 1634, four years after his death.

Jeremiah Horrocks in England observed in 1637 the dark limb of the Moon occult the stars of the Pleiades cluster, one by one. If the Moon possessed an atmosphere, the starlight would have flickered and faded as it was attenuated and refracted by the gas, but in each case the star’s disappearance was instantaneous.

In 1638 John Wilkins, an English clergyman, published Discovery of a World in

the Moone; Or a Discourse tending to prove that ’tis probable there may be another Habitable World in that Planet. He took a serious look at how a voyage to the Moon might be attempted utilising some form of ‘engine’. Wilkins was so enthusiastic that after he helped to establish the Royal Society of London in 1660 he had this petition the government to undertake such a venture with the objective of claiming the Moon for the British Empire!