The Quest for Long-Range Supersonic Cruise

Two users were looking to field airplanes in the 1960s with long range at high speeds. One organization’s requirement was high profile and the object of much debate: the United States Air Force and its continuing desire to have an intercontinental range supersonic bomber. The other organization was operating in the shadows. It was the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and it was aiming to replace its covert subsonic high-altitude reconnaissance plane (the Lockheed U-2). The requirement was simple; the fulfillment would be challenging, to say the least: a mission radius of 2,500 miles, cruising at Mach 3 for the entire time, at altitudes up to 90,000 feet. The payload was to be on the order of 800 pounds, as it was on the U-2.

The evolution of both supersonic cruise aircraft was involved, much more so for the highly visible USAF aircraft that eventually appeared as the XB-70. The B-58 had given the USAF experience with a Mach 2 bomber, but bombing advocates (notably Gen. Curtis LeMay) wanted long range to go with the supersonic performance. As demonstrated in the classic Breguet range equation, range is a direct function of

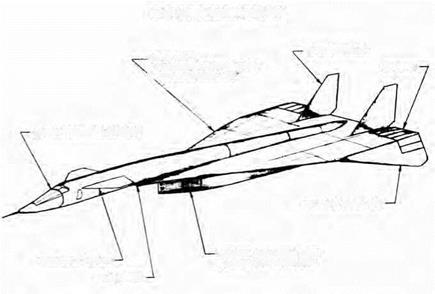

lift-to-drag (L/D) ratio. The high drag at supersonic speeds reduced that ratio to the point where large fuel tanks were necessary, increasing the weight of the vehicle, requiring more lift, more drag, and more fuel. Initial designs weighed 750,000 pounds and looked like a "3-ship formation.” NACA research on the XF-92 had suggested a delta wing design as an efficient high-speed shape; now, a paper written by Alfred Eggers and Clarence Syvertson of Ames published in 1954 studied simple shapes in the supersonic wind tunnels. They noted that, by mounting a wing atop a half cylindrical shape, they could use the pressure increase behind the shape’s shock wave to increase the effective lift of the wing.[1066] A lift increase of up to 30 percent could be achieved. This concept was dubbed "compression lift”; more recently, it is referred to as the "wave rider” concept. Using compression lift principles, North American Aviation (NAA) proposed a 6-engined aircraft weighing 500,000 pounds loaded that could cruise at Mach 2.7 to 3 for 5,000 nautical miles. The aircraft would have a delta wing, with a large underslung shape housing the propulsion system, weapons bay, landing gear, and fuel tanks. A canard surface behind the cockpit would provide trim lift at supersonic speeds. To provide additional directional stability at high speeds, the outer wingtips would fold to either 25 or 65 degrees down. Although reducing effective wing lifting surface, it would have an additional benefit of further increasing compression lift caused by wingtip shocks reflecting off the underside of the wing. Because of the 900-1,100-degree sustained skin temperature at such high cruise speeds, the aircraft would be made of titanium and stainless steel, with stainless steel honeycomb being used in the 6,300-square-foot wing to save weight.[1067]

![]() Original goals were for the XB-70, as it was designated, to make its first flight in December 1961, after contract award to NAA in January 1958. But the development of the piloted bomber was colliding with the missile and space age. The NACA now became the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and the research organization gained the mission of directing the Nation’s civilian space program, as well as its traditional aeronautics advancement focus. For military aviation, the development of reliable intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM)

Original goals were for the XB-70, as it was designated, to make its first flight in December 1961, after contract award to NAA in January 1958. But the development of the piloted bomber was colliding with the missile and space age. The NACA now became the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and the research organization gained the mission of directing the Nation’s civilian space program, as well as its traditional aeronautics advancement focus. For military aviation, the development of reliable intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM)

В-70 AERODYNAMIC FEATURES

В-70 AERODYNAMIC FEATURES

![]()

![]() DELTA WING

DELTA WING

![]()

DROOPED LEAOING EDGES 4 “COMPRESSION LIFT’

BLC GUTTER

North American Aviation (NAA) XB-70 Valkyrie. NASA.

promised delivery of atomic payloads in 30 minutes from launch. The deployment by the Soviet Union of supersonic interceptors armed with supersonic air-to air missiles and belts of Mach 3 surface-to-air missiles (SAM) increasingly made the survivability of the unescorted bomber once again in doubt. The USAF clung to the concept of the piloted bomber, but in the face of delays in manufacturing the airframe with its new materials, increasing program costs, and the concerns of the new Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, the program was scaled back to an experimental program with only four (later three, then two) aircraft to be built. The Air Force’s loss was NASA’s gain; a limited test program of 180 hours was to be flown, with the USAF and NASA sharing the cost and the data. At last, a true supersonic cruise aircraft would be available for the NACA’s successor to study in the sky. The long-awaited first flight of XB-70 No. 1 occurred before a large crowd at Palmdale, CA, on September 21, 1964. But the other shadow supersonic cruise aircraft had already stolen a march on the star of the show.

In February 1964, President Lyndon Johnson revealed to the world that the United States was operating an aircraft that cruised at Mach 3 at latitudes over 70,000 feet. Describing a plane called the A-11, the initial press release was misleading—deliberately so. The A-11 name was a misnomer; it was a proposed design for the CIA spy plane that was never

built, as it had too large a radar cross section. The photograph released was of a slim, long aircraft with two huge wing-mounted engines: the two-seat USAF interceptor version, known as the YF-12. Only three were built, and they were not put into production. The "A-11” that was flying was actually known as the A-12 and was the single-seat low-radar cross-section design plane built in secret by the Lockheed team led by Kelly Johnson, designer of the original U-2. Built almost exclusively of titanium, the aircraft had to be extremely light to achieve its altitude goal; its long range also dictated a high fuel fraction. The twin J58 turbojets had to remain in afterburner for the cruise portion, which dictated even higher-temperature materials than titanium and unique attention to the thermal environment of the vehicle.[1068] [1069]

![]() The USAF ordered a two-seat reconnaissance version of the A-12, designated the SR-71 and duly announced by the President in summer 1964, before the Presidential election. The single-seat A-12 existence was kept secret for another 20 years at CIA insistence, which had a significant impact on NASA’s flight test of the only other Mach 3 piloted aircraft besides the XB-70. Later known collectively known as Blackbirds, a fleet of 50 Mach 3 cruise airplanes were built in the 1960s and operated for over 25 years. But the labyrinth of secrecy surrounding them severely hampered acquisition by NASA of an airplane for research, much less investigating their technical details and publishing reports. This was unfortunate, as now the United States was committed to not only a space race, but also a global race for a new landmark in aviation technology: a practical supersonic jet airliner, more popularly known as the Supersonic Transport (SST). The emerging NASA would be a major participant in this race, and in 1964, the other runners had a headstart.

The USAF ordered a two-seat reconnaissance version of the A-12, designated the SR-71 and duly announced by the President in summer 1964, before the Presidential election. The single-seat A-12 existence was kept secret for another 20 years at CIA insistence, which had a significant impact on NASA’s flight test of the only other Mach 3 piloted aircraft besides the XB-70. Later known collectively known as Blackbirds, a fleet of 50 Mach 3 cruise airplanes were built in the 1960s and operated for over 25 years. But the labyrinth of secrecy surrounding them severely hampered acquisition by NASA of an airplane for research, much less investigating their technical details and publishing reports. This was unfortunate, as now the United States was committed to not only a space race, but also a global race for a new landmark in aviation technology: a practical supersonic jet airliner, more popularly known as the Supersonic Transport (SST). The emerging NASA would be a major participant in this race, and in 1964, the other runners had a headstart.