Whitcomb and History

Aircraft manufacturers tried repeatedly to lure Whitcomb away from NASA Langley with the promise of a substantial salary. At the height of his success during the supercritical wing program, Whitcomb remarked: "What you have here is what most researchers like—independence. In private industry, there is very little chance to think ahead. You have to worry about getting that contract in 5 or 6 months.”[256] Whitcomb’s independent streak was key to his and the Agency’s success. His relationship with his immediate boss, Laurence K. Loftin, the Chief of Aerodynamic Research at Langley, facilitated that autonomy until the late 1970s. When ordered to test a laminar flow concept that he felt was impractical in the 8-foot TPT, which was widely known as "Whitcomb’s tunnel,” he retired as head of the Transonic Aerodynamics Branch in February 1980. He had worked in that organization since coming to Hampton from Worcester 37 years earlier, in 1943.[257]

Whitcomb’s resignation was partly due to the outside threat to his independence, but it was also an expression of his practical belief that his work in aeronautics was finished. He was an individual in touch with major national challenges and having the willingness and ability to devise solutions to help. When he made the famous quote “We’ve done all the easy things—let’s do the hard [emphasis Whitcomb’s] ones,” he made the simple statement that his purpose was to make a difference.[258] In the early days of his career, it was national security, when an innovation such as the area rule was a crucial element of the Cold War tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union. The supercritical wing and winglets were Whitcomb’s expression of making commercial aviation and, by extension, NASA, viable in an environment shaped by world fuel shortages and a new search for economy in aviation. He was a lifelong workaholic bachelor almost singularly dedicated to subsonic aerodynamics. While Whitcomb exhibited a reserved personality outside the laboratory, it was in the wind tunnel laboratory that he was unrestrained in his pursuit of solutions that resulted from his highly intuitive and individualistic research methods.

With his major work accomplished, Whitcomb remained at Langley as a part-time and unpaid distinguished research associate until 1991. With over 30 published technical papers, numerous formal presentations, and his teaching position in the Langley graduate program, he was a valuable resource for consultation and discussion at Langley’s numerous technical symposiums. In his personal life, Whitcomb continued his involvement in community arts in Hampton and pursued a new quest: an alternative source of energy to displace fossil fuels.[259]

Whitcomb’s legacy is found in the airliners, transports, business jets, and military aircraft flying today that rely upon the area rule fuselage, supercritical wings, and winglets for improved efficiency. The fastest, highest-flying, and most lethal example is the U. S. Air Force’s Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor multirole air superiority fighter. Known widely as the 21st Century Fighter, the F-22 is capable of Mach 2 and features an area rule fuselage for sustained supersonic cruise, or supercruise, performance and a supercritical wing. The Raptor was an outgrowth of the Advanced Tactical Fighter (ATF) program that ran from 1986 to 1991. Lockheed designers benefited greatly from NASA work in fly-by-wire control, composite materials, and stealth design to meet the mission of the new aircraft. The Raptor made its first flight in 1997, and production aircraft reached Air Force units beginning in 2005.[260]

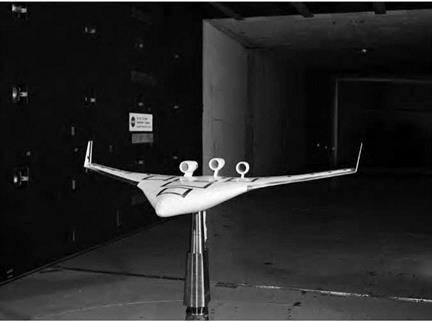

Whitcomb’s ideal transonic transport also included an area rule fuselage, but because most transports are truly subsonic, there is no need for that design feature for today’s aircraft.[261] The Air Force’s C-17 Globemaster III transport is the most illustrative example. In the early 1990s, McDonnell-Douglas used the knowledge generated with the YC-15 to develop a system of new innovations—supercritical airfoils, winglets, advanced structures and materials, and four monstrous high-bypass turbofan engines—that resulted in the award of the 1994 Collier Trophy. After becoming operational in 1995, the C-17 is a crucial element in the Air Force’s global operations as a heavy-lift, air-refuelable cargo transport.[262] After the C-17 program, McDonnell-Douglas, which was absorbed into the Boeing Company in 1997, combined NASA-derived advanced blended wing body configurations with advanced supercritical airfoils and winglets with rudder control surfaces in the 1990s.[263]

Unfortunately, Whitcomb’s tools are in danger of disappearing. Both the 8-foot HST and the 8-foot TPT are located beside each other on Langley’s East Side, situated between Langley Air Force Base and the Back River. The National Register of Historic Places designated the Collier-winning 8-foot HST a national historic landmark in October 1985.[264] Shortly after Whitcomb’s discovery of the area rule, the NACA suspended active operations at the tunnel in 1956. As of 2006, the Historic Landmarks program designated it as "threatened,” and its future

disposition was unclear.[265] The 8-foot TPT opened in 1953. He validated the area rule concept and conducted his supercritical wing and wing- let research through the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s in this tunnel, which was located right beside the old 8-foot HST. The tunnel ceased operations in 1996 and has been classified as "abandoned” by NASA.[266] In the early 21st century, the need for space has overridden the historical importance of the tunnel, and it is slated for demolition.

Overall, Whitcomb and Langley shared the quest for aerodynamic efficiency, which became a legacy for both. Whitcomb flourished working in his tunnel, limited only by the wide boundaries of his intellect and enthusiasm. One observer considered him to be "flight

|

A 3-percent scale model of the Boeing Blended Wing Body 450 passenger subsonic transport in the Langley 14 x 22 Subsonic Tunnel. NASA. |

theory personified.”[267] More importantly, Whitcomb was the ultimate personification of the importance of the NACA and NASA to American aeronautics during the second aeronautical revolution. The NACA and NASA hired great people, pure and simple, in the quest to serve American aeronautics. These bright minds made up a dynamic community that created innovations and ideas that were greater than the sum of their parts. Whitcomb, as one of those parts, fostered innovations that proved to be of longstanding value to aviation.