STS-96

|

Int. Designation |

1999-030A |

|

Launched |

27 May 1999 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39B, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

6 June 1999 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 15, Shuttle Landing Facility, KSC, Florida |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-103 Discovery/ET – 100/SRB BI-100/SSME #1 2047; |

|

#2 0251; #3 2049 |

|

|

Duration |

9 days 19 hrs 13 min 57 sec |

|

Call sign |

Discovery |

|

Objective |

ISS assembly flight 2A.1; logistics mission |

Flight Crew

ROMINGER, Kent Vernon, 42, USN, commander, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-73 (1995); STS-80 (1996); STS-85 (1997)

HUSBAND, Rick Douglas, 41, USAF, pilot

JERNIGAN, Tamara Elizabeth, 40, civilian, mission specialist 1, 5th mission Previous missions: STS-40 (1991); STS-52 (1992); STS-67 (1995); STS-80 (1996) OCHOA, Ellen Lauri, 41, civilian, mission specialist 2, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-56 (1993); STS-66 (1994)

BARRY, Daniel Thomas, 45, civilian, mission specialist 3, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-72 (1996)

PAYETTE, Julie, 35, civilian, Canadian, mission specialist 4 TOKAREV, Valery Ivanovich, 46, Russian Air Force, mission specialist 5

Flight Log

This mission was the first logistics flight to the station in preparation for the arrival of the Russian Service Module Zvezda (“Star”) scheduled for later in 1999. Due to weight limitations on the previous STS-88 mission, not all the logistics could be taken to the station in one go. STS-96 was originally planned for later in the year, after STS-93 had deployed the Chandra X-ray telescope, but early in 1999 there were problems in the circuitry boards on Chandra which needed to be replaced, forcing the launch to be delayed. In early May, weather damage to the ET intended for STS-96 resulted in further delays for repairs. With the Russian Service Module also being delayed, further ISS Shuttle missions and the arrival of the first resident crew were put back until 2000. This meant there would be a long gap in ISS-related missions between STS-88 and support missions for the first resident crew in 2000. This gap was filled only with the STS-96 logistics mission.

After the STS-96 stack was returned to the VAB for ET tank repairs, during which 460 critical divots out of a total of 650 divots in the ET outer foam were

|

On board the Zarya module, astronauts Julie Payette (top) and Ellen Ochoa handle supplies being moved over from the docked Shuttle Discovery |

repaired, the only other concern prior to launch was when a sail-boarder ventured into the SRB recovery zone. Once that was removed, the launch proceeded smoothly. Two days after launch, Discovery completed the first docking with ISS. The Shuttle remained docked to ISS for 138 hours, during which members of the crew spent over 79 hours inside the station and 7 hours 55 minutes hours outside during the mission’s only EVA. During the 28 May EVA, Jernigan (EV1) and Barry (EV2) transferred the US-built Orbital Transfer Device crane and elements of the Russian Strela crane from the cargo bay of Discovery to their locations on the exterior of the station. They also installed EVA foot restraints that could accommodate either American or Russian EVA footwear and three bags of tools and handrails for future assembly operations. An insulation cover was placed over a trunnion pin on Unity, they inspected one of

two Early Communication Systems (Е-Com) antennas on Unity, and finally photo- documented the exterior paint surfaces of both modules.

Upon entering the station, the crew were concerned over the quality of air circulation inside Zarya, but this was solved by changing the orientation of panel doors that were interrupting the flow of air around the station. Eighteen battery recharge controllers were replaced in Zarya and mufflers were installed over fans inside the FGB to reduce noise levels in the module. The crew also transferred over 1,618 kg of logistics across to the ISS, including clothing, sleeping bags, spare parts, medical equipment and 318 litres of water. They also installed the first of a series of strain gauges, which would be important as the station expanded to record the stress on docking interfaces, and cleaned filters and checked smoke detectors. Transferred in the opposite direction was 90 kg of equipment (198 items), which was moved back into Discovery for the return to Earth.

The day before undocking, the RCS on Discovery were pulsed 17 times to boost the station’s orbit slightly, pending the arrival of the next Shuttle (which turned out to be a year later). Discovery was undocked from ISS on 4 June and after flying two circuits around the station for photo-documentation, the crew prepared for the return to Earth. One of their last tasks prior to landing was the release of a small reflective satellite, which would be a target for student observations around the world.

Milestones

212th manned space flight

124th US manned space flight

94th Shuttle mission

28th flight of Discovery

2nd Shuttle ISS mission

1st Discovery ISS mission

1st Shuttle mission to dock with ISS

|

Flight Crew

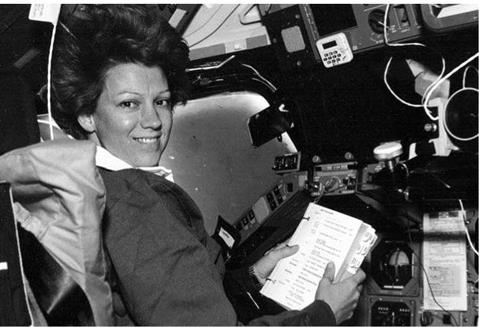

COLLINS, Eileen Marie, 42, USAF, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-63 (1995); STS-84 (1997)

ASHBY, Jeffrey Shears, 45, USN, pilot

COLEMAN, Catherine Grace (“Cady”), 38, USAF, mission specialist 1,

2nd mission

Previous mission: STS-73 (1995)

HAWLEY, Steven Alan, 47, civilian, mission specialist 2, 5th mission Previous missions: STS 41-D (1984); STS 61-C (1986); STS-31 (1990);

STS-87 (1997)

TOGNINI, Michel Ange Charles, 49, French Air Force, mission specialist 3, 2nd mission

Previous mission: Soyuz TM15 (1992)

Flight Log

If the launch of STS-93 had occurred on time on 20 July, Eileen Collins, the first female commander of a US space mission, could have taken Columbia to orbit on the 30th anniversary of the Apollo 11 lunar landing (whose Command Module was also called Columbia). However, the launch was terminated at the T — 7 second mark when more than double the permitted amount of hydrogen was detected in the aft engine compartment of the orbiter. System engineers in the firing room at KSC noted the indication and manually cut off the ground launch sequencers less than a second before SSME ignition. Post-abort evaluation determined that the reading was false. The next launch attempt, on 22 July, was scrubbed due to adverse weather conditions at KSC, but the launch attempt on 23 July was successful, the only delay being a communications problem with Columbia during the countdown which forced a seven minute slip in the launch time.

|

Eileen Collins, the first female Shuttle commander and first female commander of an American mission, looks over a checklist at the commander’s station on the forward flight deck of Columbia during FD 1 |

Five seconds after leaving the pad, flight controllers noted a voltage drop in one of the electrical buses on the Columbia. As a result of the drop in voltage, one of two redundant main engine controllers on two of the three SSME (centre and right position) shut down. But the others performed nominally, supporting the climb to orbit. However, the orbit attained was 11.2 km lower than planned due to the premature cut-off of the SSME. This was later traced to a hydrogen leak in the #3 main engine nozzle, caused by the loss of an LO pin from the main injector during engine ignition. This had struck the hot wall of the nozzle and ruptured three LH coolant tubes.

Columbia’s manoeuvring engines were used subsequently to raise the orbit to its proper altitude, allowing the deployment of the primary payload into its desired orbit. The Chandra X-Ray Observatory (formerly known as the Advanced X-Ray Astrophysical Facility, or AXAF) was successfully deployed using its two-stage IUS on FD 1. The IUS propelled the observatory into an operational orbit of approximately 10,000 x 140,000 km – at its farthest, almost one-third of the way to the Moon – in an orbital period of about 64 hours. This would permit the telescope to make 55 hours of uninterrupted observations each orbit. The primary mission of Chandra was scheduled to last five years through to 2004, although this was subsequently extended to ten years of operational activity until 2009.

During the remainder of the mission, secondary payloads and experiments were activated. These included the South-Western UV Imaging System (SWUIS) used to obtain UV imagery of Earth, the Moon, Mercury, Venus and Jupiter. The crew monitored several plant growth experiments and collected data from a biological cell culture experiment. They also evaluated the Treadmill Vibration Information System, which measured vibrations and the changes in microgravity levels caused by on-orbit exercise periods. This was important for gathering data to ensure that exercise periods on ISS did not disrupt delicate instruments and experiments. The crew also evaluated high-definition TV equipment for future use on both the Shuttle and ISS, which conformed to the latest industry standards for TV products. Tognini, who visited the Mir space station in 1992, spoke over the radio with his colleague and fellow countryman Jean-Pierre Haignere, who was on the fifth of his six-month stay on the Russian Mir space station. Collins and Ashby also evaluated the Portable In-flight Landing Operations Trainer (PILOT), which utilised a laptop computer, simulation software and a joystick combination to provide refresher and skills training to the commander and pilot prior to performing the actual landing.

Milestones

213th manned space flight 125th US manned space flight 95th Shuttle mission 26th flight of Columbia

1st female Shuttle commander and 1st US female crew commander (Collins) Shortest scheduled flight since 1990