STS-86

|

Int. Designation |

1997-055A |

|

Launched |

25 September 1997 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

6 October 1997 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 15, Shuttle Landing Facility, KSC, Florida |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-104 Atlantis/ET-88/SRB BI-090/SSME #1 2012; #2 2040; #3 2019 |

|

Duration |

10 days 19 hrs 20 min 50 sec Wolf 127 days 20hrs 0min 50 sec (landing on STS-89) |

|

Call sign |

Atlantis |

|

Objective |

7th Shuttle-Mir docking; delivery of NASA 6 (Wolf) crew member; return of NASA 5 (Foale) crew member |

Flight Crew

WETHERBEE, James Donald, 44, USN, commander, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-32 (1990); STS-52 (1992); STS-63 (1995) BLOOMFIELD, Michael John, 38, USAF, pilot

TITOV, Vladimir Georgievich, 50, Russian Air Force, mission specialist 1, 4th mission

Previous missions: Soyuz T8 (1983); Soyuz T10 abort (1983); Soyuz TM4 (1987); STS-63 (1995)

PARAZYNSKI, Scott Edward, 36, civilian, mission specialist 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-66 (1994)

CHRETIEN, Jean-Loup Jacques Marie, 59, French Air Force,

mission specialist 3, 3rd mission

Previous missions: Soyuz T6 (1982); Soyuz TM7 (1988)

LAWRENCE, Wendy Barrien, 38, USN, mission specialist 4, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-67 (1995)

NASA 6 Mir crew member up only:

WOLF, David Alan, 41, civilian, mission specialist 5, Mir EO-24 cosmonaut researcher, NASA board engineer 6, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-58 (1993)

NASA 5 Mir crew member down only:

FOALE, Colin Michael, 40, civilian, mission specialist 5, Mir EO-23 cosmonaut researcher, NASA board engineer 5, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-45 (1992); STS-56 (1993); STS-63 (1995)

|

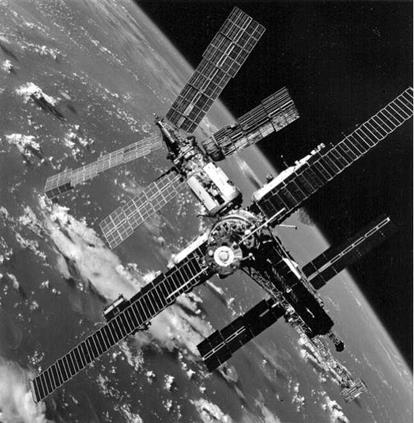

This image of Mir taken by the crew of STS-86 clearly shows the damaged Spektr module and arrays following the collision with a Progress re-supply vessel |

Flight Log

Both Scott Parazynski and Wendy Lawrence were originally in line for long flights on the Mir space station. Parazynski had been removed from long-duration training due to the fact that he was too tall to fit in the Soyuz contour seat if he needed to use one for emergency landing (he would have been launched to and from the Mir on the Shuttle under normal circumstances). Lawrence would have followed Foale on Mir, but was deemed too short to fit into an Orlan suit, a requirement introduced after the Progress collision in order to allow American astronauts to support EVA operations to repair the station should the need arise. Lawrence had never completed Orlan EVA training, as it was not part of her original programme to perform an EVA. However, she still remained part of the STS-86 Shuttle crew to visit Mir. In addition, by way of compensation for losing the duration flight she had trained so long for, she was also guaranteed a flight on the STS-89 mission that would exchange Wolf with the final US

astronaut, Andy Thomas. For some time, the three astronauts were known as Scott “Too Tall” Parazynski, Wendy “Too Short” Lawrence and Dave “Just Right” Wolf.

Regular reviews of Shuttle-Mir operations occurred prior to each docking mission, but after a fire and a collision in the space of four months, an independent and internal safety assessment was completed before NASA Administrator Dan Goldin would authorise the flight and exchange of NASA crew members. His authorisation came only an hour before the launch of STS-86. The events at Mir had seriously affected Foale’s science programme, as most of his equipment had been left in the sealed-off Spektr module. But his contribution to the recovery of the station both during and immediately after the collision had earned him high praise from Russian space officials.

Atlantis docked to Mir for the seventh (and the orbiter’s final) time on 27 September, with the exchange between Foale and Wolf accomplished the following day. During the six days of docked operations, the crew moved over four tons of material from SpaceHab/Atlantis to the space station, including over 770 kg of water, plus specimens and hardware for ISS risk mitigation experiments that would monitor the health and safety of the resident crew. A gyrodyne, batteries, three air pressurisation units, an attitude control computer and a range of other logistical items were also transferred to Mir. Coming the other way for the return to Earth were experiment samples and hardware and an old Elektron oxygen generator.

On 1 October, Parazynski (EV1) and Titov (EV2) completed a joint US/Russian EVA, a forerunner to those planned for ISS operations. During the EVA, they attached a 55-kg Solar Array Cap to the Docking Module for a future Russian EVA crew to seal off a suspected leak in Spektr’s hull. They also retrieved four Mir Environmental Effects Payloads and continued testing the SAFER units.

After undocking on 3 October, Atlantis completed a fly-around to conduct a visual inspection of the station. This included allowing air into the Spektr module to see if the Atlantis crew could detect seepage or debris particles that would help to locate the breach in the module’s hull. Particles were seen but they could not conclusively be deemed to have originated from Spektr. Two landing opportunities were waived on 5 October due to low clouds. This was the last flight of Atlantis before a planned maintenance down period, after which the vehicle would participate in the early construction flights of ISS.

Milestones

202nd manned space flight

117th US manned space flight

87th Shuttle mission

20th flight of Atlantis

7th Shuttle-Mir docking

38th US and 67th flight with EVA operations

9th SpaceHab mission (4th double module)

|

Flight Crew

KREGEL, Kevin Richard, 41, civilian, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-70 (1995); STS-78 (1996)

LINDSEY, Steven Wayne, 37, USAF, pilot CHAWLA, Kalpana, 34, civilian, mission specialist 1 SCOTT, Winston Elliott, 47, USN, mission specialist 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-72 (1996)

DOI, Takao, 43, civilian, mission specialist 3

KADENYUK, Leonid Konstantinovich, 46, Ukraine Air Force, payload specialist 1

Flight Log

Completing a sixth on-time launch for the year and ending the second year in which eight flights had been completed (the first being 1992), this was a flight of mixed fortunes. The USMP-4 payload performed well, with experiments focusing on materials science, combustion science and fundamental physics. There were other secondary and mid-deck experiments flown as well, including the Collaborative Ukrainian Experiment, which featured ten planet biology experiments.

SPARTAN 201 was on its fourth mission and this time, its experiment programme was geared towards investigating the physical conditions and processes of the hot outer layers of the sun’s atmosphere – the Solar Corona. The SPARTAN was also to gather information on the solar wind. Originally, SPARTAN was to be deployed on FD 2, but a companion spacecraft, the Solar and Hemispheric Observatory (SOHO), had a temporary power problem and so the deployment was delayed by 24 hours. On FD 3, the RMS was used to lift the SPARTAN out of the bay, but the spacecraft failed to initiate a pirouette manoeuvre. This indicated a problem with the attitude control system, which would be required for finer pointing towards solar targets. During an attempted recapture, the RMS did not secure a firm grip and when

|

Winston Scott releases a prototype free-flying experiment, the Autonomous EVA Robotic Camera (AEROCam) Sprint. The EVA was also the first by a Japanese astronaut (Doi – out of frame) and included the capture of the Spartan satellite seen to the right of Scott |

it was retracted, it imparted a small rotational spin on the satellite of about 2 degrees per second. The crew tried to match this rotation by firing the orbiter’s thrusters for a second grapple attempt, but this was called off by the flight controllers. Instead, a plan was devised for the EVA crew to capture the satellite by hand allowing it to be stowed back into the payload bay.

The original plan for the EVA was amended to include the SPAS capture, which was achieved on 24 November. Scott (EV1) and Doi (EV2) manually grappled the satellite, allowing Chawla to use the RMS to grab the satellite and gently lower it into the payload bay. A review of further operations with SPARTAN would be conducted by mission management prior to trying to release it a second time. After the satellite was secured, the EVA crew continued with their planned programme of activities, designed to support forthcoming ISS assembly missions. This included working with a crane which was installed on the port side of the payload bay. The EVA lasted 7 hours 3 minutes.

After completing most of their experiment programme, the crew received the news that a second EVA would be added to the flight, but the SPARTAN would not be released again. The risk of being unable to retrieve the unit again was too great and the orbiter’s fuel reserves were insufficient to support all contingencies. SPARTAN 201-04 therefore would not free-fly again on this mission, though it was later raised on the end of the RMS to test the video and laser sensors of the Automated Rendezvous and Capture System. The EVA crew also deployed the AEROCam Sprint, a prototype free-flying TV camera that could be utilised for remote inspections of the exterior of ISS and for visual inspections of hazardous locations which would be difficult for a suited EVA astronaut to safely reach. This second EVA, on 3 December, lasted 4 hours 59 minutes.

Milestones

203rd manned space flight

118th US manned space flight

88th Shuttle mission

24th flight of Columbia

39th US and 68th flight with EVA operations

1st Japanese to perform EVA (Doi)

4th flight of USMP payload

12th EDO mission

1st EVAs from Columbia