STS-9

|

Int. Designation |

1983-116A |

|

Launched |

28 November 1983 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

8 December 1983 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 17, Edwards Air Force Base, California |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-102 Columbia/ET-11/SRB A55; A60/SSME #1 2011; #2 2018; #3 2019 |

|

Duration |

10 days 7 hrs 47 min 23 sec |

|

Callsign |

Columbia |

|

Objective |

First flight of European-built Spacelab pressurised scientific laboratory (Spacelab 1) |

Flight Crew

YOUNG, John Watts Jr., 53, USN, commander, 6th mission Previous missions: Gemini 3 (1965); Gemini 10 (1966); Apollo 10 (1969); Apollo 16 (1972), STS-1 (1981)

SHAW, Brewster Hopkinson Jr., 38, USAF, pilot

GARRIOTT, Owen Kay, 53, civilian, mission specialist 1, 2nd mission

Previous mission: Skylab 3 (1973)

PARKER, Robert Allan Ridley, 46, civilian, mission specialist 2 MERBOLD, Ulf, 42, civilian, payload specialist 1 LICHTENBERG, Byron Kurt, 35, civilian, payload specialist 2

Flight Log

This mission, originally scheduled for 30 September, was delayed for a month to allow time for Columbia’s SRB nozzles to be replaced following the STS-8 launch scare. The Shuttle rose from Pad 39A at 16: 00 hrs local time at the Kennedy Space Center, carrying a unique crew of six, including the apparently ageless veteran of space flight, John Young, in the commander’s seat. Columbia performed a startling 140° roll programme to place it on an azimuth heading for a 57° inclination orbit – the highest achieved on a US manned space flight. As a result, the Shuttle could be seen passing over Britain just after entering its orbit, which would have a maximum altitude of 216 km (134 miles).

On the schedule was a nine-day intensively scientific mission aboard the first Spacelab payload bay-mounted laboratory. This was built by the European Space Agency as a result of an agreement signed with NASA ten years earlier, at a cost of $850 million. The nine-day mission, which featured the first time that the principal investigators could talk directly to experiments in space via the TDRS-1 relay satellite, was judged a phenomenal success. Altogether, 73 separate investigations were

|

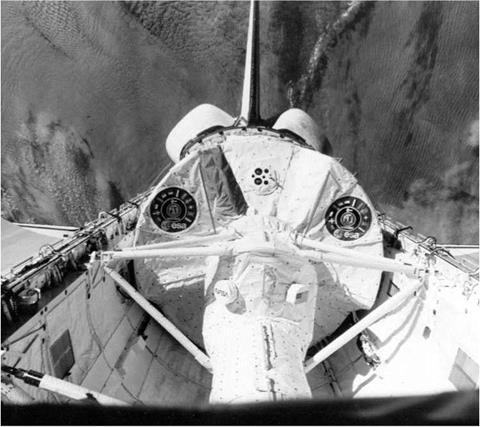

The Spacelab 1 Module in Columbia’s payload bay. In the foreground is the access tunnel from the Shuttle mid-deck |

completed in the fields of astronomy, physics, atmospheric physics, Earth observations, life sciences, material sciences, space plasma physics and technology. The crew split into two shifts which lasted twelve hours, sometimes more like eighteen hours, so much so that mission controllers extended the mission. The Red Shift comprised Young, Parker and Merbold (representing ESA), while the Blue Shift included Shaw, Garriott and Lichtenberg (representing the American science community).

Strapped in their seats and ready to come home, the crew got an unplanned nine hour flight extension when a major computer failure stopped the OMS retro-burn just before it started. Computer 1 failed, then computer 2, which had taken over operations instantly, also shut down. Young and his pilot Brewster Shaw sweated over troubleshooting the problem, and with everything crossed, fired the OMS engines for another try. The computer fault had been due to contaminated integrated circuits. All went well and Columbia homed in on Edwards Air Force Base’s dry lake bed runway 17, landing at T + 10 days 7 hours 47 minutes 23 seconds, the longest six-crew

mission. Two minutes later, the troubled Columbia caused another scare by catching fire, leaking hydrazine from an APU being the cause. As the pilot and commander winged their way to Houston, the four other crewmen took part in intensive life sciences investigations, which included another dose of zero-G in a KC-135 aircraft.

Milestones

94th manned space flight

40th US manned space flight

9th Shuttle mission

6th flight of Columbia

1st Spacelab Long Module mission

1st flight with six crew members

1st flight to carry a West German

1st flight with crew member on sixth mission

1st US flight with non-American crew member

1st flight with payload specialist crew members