STS-7

|

Int. Designation |

1983-026A |

|

Launched |

18 June 1983 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

24 June 1983 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 15, Edwards Air Force Base, California |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-099 Challenger/ET-7/SRB A51; A52/SSME #1 2017; #2 2015; #3 2012 |

|

Duration |

6 days 2 hrs 23 min 59 sec |

|

Callsign |

Challenger |

|

Objective |

Commercial satellite deployment mission; space adaptation medical investigations |

Flight Crew

CRIPPEN, Robert Laurel, 45, USN, commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-1 (1981)

HAUCK, Frederick “Rick” Hamilton, 42, USN, pilot FABIAN, John McCreary, 44, USAF, mission specialist 1 RIDE, Sally Kristen, 32, civilian, mission specialist 2 THAGARD, Norman Earl, 39, civilian, mission specialist 3

Flight Log

By contrast to the Soviet reaction to the flight of Svetlana Savitskaya in 1982, the US launch of Sally Ride was played down as much as possible by NASA and by the lady herself, not with total success. The on-time lift-off occurred at 07: 33 hrs local time and after MECO, two OMS burns were required to carry Challenger to its operational 28.45° orbit with a maximum altitude of 272 km (169 miles). Crippen, the first person to fly the Shuttle for a second time, described the launch as a bit smoother than he remembered on STS-1.

The first commercial satellite payload was delivered into orbit at T + 9 hours 29 minutes, with an accuracy estimated at within 457 m (1,500 ft) of the target point and within 0.085° of the required pointing vector. Canada’s Anik 2C later made its way into geostationary orbit. The following day, satellite number two, India’s Palapa, was safely deployed. With the commercial trucking mission over, the crew got down to the third satellite deployment, that of the West German SPAS free flier, using the Remote Manipulator System (RMS) arm operated by John Fabian. Almost immediately, Fabian grabbed the satellite, demonstrating the first satellite retrieval. SPAS was released again and Crippen moved Challenger 300 m (984 ft) away and performed a series of station-keeping manoeuvres. Cameras on SPAS, meanwhile, took spec-

|

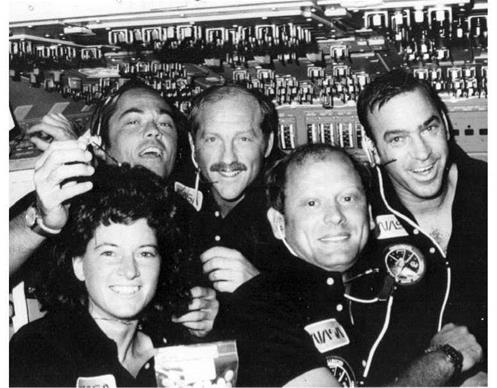

Clockwise from top left: Crippen, Hauck, Fabian, Thagard and Ride, the crew of STS-7 |

tacular photos of Challenger in space, with the RMS arm conveniently cocked in the shape of a number 7.

Six science experiments were on board and these operated for nine-and-a-quarter hours autonomously before the free flier was retrieved, this time by Sally Ride. The third mission specialist, the flight doctor Norman Thagard, who had been added to the crew to study space adaptation syndrome, even had a go at using the RMS. A complement of onboard experiments was operated by the crew, including the first demonstration of the Shuttle’s Ku-band rendezvous radar system and a reduction in cabin pressure from 760 mm (3in) to 527 mm (2 in) for 30 hours to investigate the possibility of eliminating the required three-and-a-half hours pre-breathing period for EVA astronauts.

The high point of the mission was to be Challenger’s return to the Kennedy Space Center, the first such return to launch site in history. Bad weather thwarted the attempt and Crippen was diverted to Edwards Air Force Base to land on runway 15. His request for a two day orbital extension was turned down because of concerns over one of the APUs on Challenger. Mission time was T + 6 days 2 hours 23 minutes 59 seconds.

Milestones

91st manned space flight 38th US manned space flight 7th Shuttle flight 2nd flight of Challenger 1st flight with five crew 1st US female in space

|

Flight Crew

LYAKHOV, Vladimir Afanasevich, 42, Soviet Air Force, commander, 2nd mission

Previous mission: Soyuz 32 (1979)

ALEKSANDROV, Aleksandr Pavlovich, 40, civilian, flight engineer

Flight Log

Following the docking failure of Soyuz T8, the next crew were assigned to complete most of the tasks planned for the previous one. However, Titov and Strekalov had conducted extensive EVA training which the T9 crew had not, so the plan was to launch Soyuz T10 with Titov and Strekalov aboard to take over from the T9 crew and conduct the extensive EVAs they had trained for.

Soyuz T9, with a crew of two rather than the expected three (due to additional propellant load), took off from Baikonur at 15: 12hrs local time, and just over a day later docked at the rear of Salyut 7 to start a mission that would, according to mission controller Valery Ryumin, be shorter than Soyuz T5’s 211 days. They almost did not make it as, for the first time since Soyuz 1, one of the twin solar panels on Soyuz failed to deploy (although this did not prevent the docking with the Salyut), a fact not revealed for 20 years. The crew, Vladimir Lyakhov and rookie flight engineer Aleksandr Aleksandrov, were the first to operate using a Heavy Cosmos module, No.1443, attached to the front of Salyut 7. This two-part spacecraft contained a 1.5 m3 (50 ft3) habitable module, an Instrument Module, and a descent capsule capable of returning 500 kg (1,103 lb) to Earth. The module was equipped with 38 m2 (40 ft2) of solar panels, providing 3 kW of electricity.

Lyakhov and Aleksandrov got down to work producing virus cells and conducting Earth resources surveys, saving Soviet citizens from disaster by warning of the formation of a lake from a melting glacier which threatened to flood several towns beneath. While the crew were inside Soyuz T9 conducting a mock evacuation exercise,

|

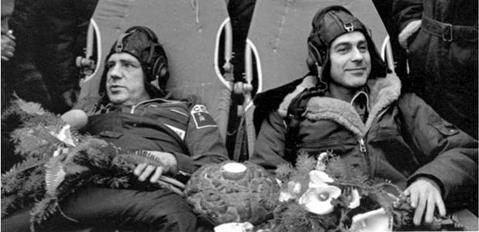

With a traditional traveller’s gift of bread and salt (as well as flowers), the T9 crew relax after their recovery from the mission. Lyakhov is on the left, Alexandrov on the right |

one of Salyut’s 14mm (1 in) thick windows was pitted to a depth of 4mm (0.16 in) by the impact of an unidentified object.

Cosmos 1443 separated from Salyut 7 on 14 August and, while flying autonomously, returned its descent capsule containing film and some equipment. It landed 100 km (62 miles) southeast of Arkalyk on 23 August. The major part of Cosmos was destroyed during re-entry on 19 September. Soyuz T9 had been flown from the back of Salyut to the front to prepare for the arrival of Progress 17 on 19 August. Progress left on 17 September, leaving the port free for the Soyuz T10 crew, who were to have been launched on 27 September to help with repairs, including an EVA to correct solar panel problems and add additional panels to increase the electrical supply on board the station.

By this time, Salyut 7 was in pretty bad shape, propellant leaks leaving the station with little manoeuvrability. Salyut’s back-up main engine was also crippled and a solar panel failure had reduced solar power. A major incident occurred on 9 September during the refuelling operations by Progress 17. A Salyut fuelling line used to feed oxidiser from the Progress to the Salyut ruptured. With only half of the 32 thrusters working, it seemed likely Salyut would have to be abandoned, but a decision was made to work around the problem and let the current mission continue while options for repair were evaluated. After the Soyuz T10 crew failed to reach orbit following the first on-the-pad launch abort in history, rumours spread in the west that Lyakhov and Aleksandrov were stranded in space, particularly as the Soyuz T9 ferry was exceeding its 115-day lifetime, according to the rumours, which created sensational press stories.

The flight continued, and a Progress ferry craft was launched to Salyut, on 21 October, carrying new solar panels, fuel and equipment. It also provided a means of propulsion for the crippled station. The crew even made two spacewalks on 1 and 3 November, lasting 2 hours 50 minutes and 2 hours 55 minutes respectively, to erect new solar panels, while cosmonauts Leonid Kizim and Vladimir Solovyov carried out a simulated EVA at the same time in the neutral buoyancy tank at Star City. The two cosmonauts on Salyut had not trained to perform such complicated EVAs and struggled to complete the tasks, as reflected in the durations of each spacewalk. The tasks had originally been planned to be completed during one EVA, but were spread over two EVAs due to the cosmonauts’ inexperience. First-time space explorer Alexandrov was amazed by the whole experience of EVA and at one point casually discarded a small unwanted item into space to see what happened. This earned him a rebuke from Mission Control, who feared confusing the station’s stellar orientation system into “thinking” that the light refection from the object might be a star. Progress separated on 13 November and the so-called doomed cosmonauts made an unheralded landing on 23 November, at T + 149 days 10 hours 46 minutes. Maximum altitude reached in the 51.6° orbit was 354 km (220 miles). The unexpected extension to the mission had gave rise to concerns over the reliability of Soyuz T in supporting a crew after such a long time in space. Soyuz T9 proved such fears were unfounded, however, and the recovery occurred without incident, giving great confidence for longer Soyuz T-supported station residences.

Milestones

92nd manned space flight

54th Soviet manned space flight

47th manned Soyuz space flight

8th manned Soyuz T space flight

7th Soviet and 23rd flight with EVA operations

Lyakhov celebrates his 42nd birthday in space (20 July)