STS-3

|

Int. Designation |

1982-022A |

|

Launched |

22 March 1982 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

30 March 1982 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 17, Northrup Strip, White Sands, New Mexico |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-102 Columbia/ET-4/SRB A11; A12/SSME #1 2007; |

|

#2 2006; #3 2005 |

|

|

Duration |

8 days 0 hrs 4 min 45 sec |

|

Callsign |

Columbia |

|

Objective |

Third Orbital Test Flight (OFT-3) |

Flight Crew

LOUSMA, Jack Robert, 46, USMC, commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: Skylab 3 (1973)

FULLERTON, Charles Gordon “Gordo”, 45, USAF, pilot

Flight Log

When Columbia returned to the Kennedy Space Center after STS-2, it was scheduled to be launched again on 22 March 1982. It was launched into murky skies, watched by one of the largest crowds since the moonshots, at 11: OOhrs local time. The first two minutes on the SRBs were enough for Lousma to describe the experience as a real barnburner, during which the vibrations caused the loss of 37 tiles from the nose and rear. His attention was diverted by an overheating APU which had to be shut down and when he got into his 38° inclination orbit, he became sick, repeating his experience of Skylab 3.

Lousma and his balding rookie pilot Gordon Fullerton started work on a hectic schedule of test flying and science. The RMS was to be tested heavily, moving two payloads around but not actually deploying them. The failure of TV cameras on the RMS, however, meant the cancellation of testing with the heaviest payload, although some operations were permitted with the Plasma Diagnosis Package. Other niggling failures, including the much-publicised toilet, were rather over-emphasised in the media, giving STS-3 a reputation it did not necessarily deserve.

Columbia was given long hot and cold soaks, pointing in the same direction for up to 80 hours, exposing it to temperatures of between — 66°C and +93°C. One of these cold soaks froze a fitment on one of the payload bay doors which refused to close properly. The mission, which reached a maximum altitude of 204 km (127 miles), was to last seven days and to end at White Sands for a change, because the runway at Edwards Air Force Base was waterlogged. Just 4O minutes before retro-fire, Columbia was waived off by high winds and given a day’s extension. When she finally came home

|

STS-3 lands at White Sands, New Mexico |

to the Northrup Strip’s runway at T + 8 days 0 hours 4 minutes 45 seconds, Lousma caused a scare by looking as though he was trying to take off again, at a record Shuttle landing speed of 404 kph (251 mph), when he over-corrected what he thought was excessive nose pitch down rate.

Milestones

83rd manned space flight 34th US manned space flight 3rd Shuttle flight 3rd flight of Columbia

|

Flight Crew

BEREZOVOY, Anatoly Nikolayevich, 40, Soviet Air Force, commander LEBEDEV, Valentin Vitalyevich, 40, civilian, flight engineer, 2nd mission Previous mission: Soyuz 13 (1973)

Flight Log

With Salyut 6 and its Heavy Cosmos module orbiting somewhat uselessly, on 19 April 1982 the Soviets launched Salyut 7 (DOS 5-2/1982-033A), similar to Salyut 6 although its interior was fitted with an eye to decor. It was equipped with the Salyut 6-type MKF and Kate telescopes and a new large X-ray telescope for astronomy. Improved medical and physical exercise machines were incorporated, and on the outside the space station had extra handholds to improve EVA productivity. The three solar panels, too, were fitted with an attachment that could hold new, secondary sets of panels. The primary docking port was equipped to accommodate the Heavy Cosmos class modules comfortably and safely, and there were also new portholes.

The first crew to inhabit Salyut 7 was launched at 15: 58 hrs local time on 13 May. It comprised rookie commander Anatoly Berezovoy and the experienced flight engineer Valentin Lebedev, a nit-picking duo who were soon to build up such a bad relationship that they only spoke to each other when necessary during the first 200-day long mission in history, which, no doubt fortunately for them, included the visit of a French cosmonaut and the first lady in space since Valentina Tereshkova. Soon after boarding, Berezovoy and Lebedev hand-deployed a small Iskra communications satellite from an airlock, the first such deployment by the Soviets and the first from a space station. Progress 13 then arrived on 25 May, to stock up the station for the long-duration medical and science mission.

The cosmonauts operated cameras, the new telescope, a Kristall materials processing furnace, a star sensor and the Oasis plant growing cabinet. The first visit occurred on 25 June, when French cosmonaut Jean-Loup Chretien and two Soviets came aboard in Soyuz T6 for a short stay. Another Progress, No.14, arrived on 12 July

|

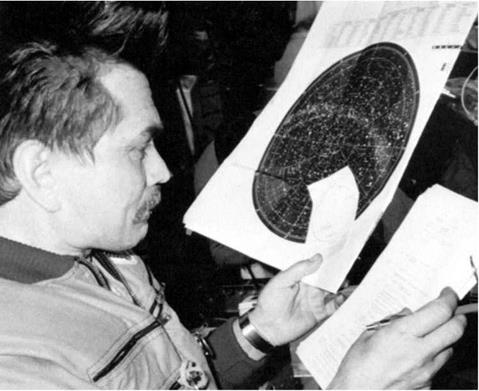

Where off Earth are we? Berezovoy consults the star charts during the long, 211-day mission |

bearing more cargo, water and fuel. The first Salyut 7 spacewalk was made on 30 July, with the cosmonauts spending 2 hours 33 minutes outside retrieving samples that had been exposed to space and replacing some science equipment. Lebedev was the prime EVA crewman, with his commander supporting activities with a television camera to provide some live pictures for the folks at home. The flight engineer also conducted some space assembly tests under the code name Pamyat, in which joints between girders were made and assessed.

By 20 August, this altogether highly successful mission was receiving Svetlana Savitskaya and two male colleagues from Soyuz T7, and afterwards two more Progress tankers, 15 and 16, came to roost. The cosmonauts, who reached a maximum altitude of 374 km (232 miles) during the 51.6° mission, had even launched another Iskra communications satellite. A manned crew changeover was expected later in the year but never came. Apparently it was decided to bring Berezovoy and Lebedev home earlier than anticipated, before the New Year rather than after.

They had a rough return, coming back at T + 211 days 9 hours 4 minutes 32 seconds aboard the fresh Soyuz T7, which landed hard, turned over and rolled down a slope. Lebedev ended up on top of his commander. The weather conditions were so awful – thick fog, heavy snow and temperatures of — 18°C – that helicopters could not reach them for a day. The pale, tired and drawn duo had to wait 20 minutes for a ground team to reach them and ended up spending the night in the back of a truck! When the helicopter did arrive, it crash-landed and the second vehicle had to be talked down by the commander of the first.

The cosmonauts had lost several pounds in weight, their red blood counts were reduced, and their pulse rates and blood pressure were high. Indeed, Berezovoy and Lebedev were reported to be still suffering from a space hangover by mid-January. On 2 March 1983, the Soviets launched another Heavy Cosmos module, Cosmos 1443. This was similar to the Cosmos 1267 module attached to Salyut 6, with a re-entry capsule at the front. Cosmos 1443 docked with Salyut 7 on 10 March, in preparation for a new manned occupation.

Milestones

84th manned space flight

50th Soviet manned space flight

43rd Soyuz manned space flight

4th Soyuz T manned mission

1st “operational” Soyuz T flight

1st manned space flight over 200 days

New duration record – 211 days 9 hours

6th Soviet and 21st flight with EVA operations

|

Flight Crew

DZHANIBEKOV, Vladimir Aleksandrovich, 40, Soviet Air Force, commander, 3rd mission

Previous missions: Soyuz 27 (1978); Soyuz 39 (1981) IVANCHENKOV, Aleksandr Sergeyevich, 41, civilian, flight engineer, 2nd mission

Previous mission: Soyuz 29 (1978)

CHRETIEN, Jean-Loup, 44, French Air Force, cosmonaut researcher

Flight Log

The highlight to France’s long-term cooperation with the Soviet Union in space was the decision in 1980 to fly a national cosmonaut. However, the cooperation between the chosen man, Jean-Loup Chretien and the chosen commander, Yuri Malyshev, in 1981, was not very smooth, leading to Malyshev’s replacement by Vladimir Dzhanibekov, with flight engineer Aleksandr Ivanchenkov making up the numbers. The highly qualified Chretien had been forbidden by Malyshev to touch anything during simulations and was so frustrated that he took a pillow along with him for one simulation at Star City and went to sleep during the session, much to Malyshev’s exasperation.

Relations improved with a new commander in the seat, and at 22: 29 hrs local time on 24 June, Soyuz T6 ascended, watched by French officials from a stand some 1,800 m (5,905 ft) away. Before the mission the prime crew and back-up crews had drawn lots to decide which emergency situations they would cope with during final simulator training. Chretien and his colleagues came out with automatic docking failure, which was repeated in space when the spacecraft’s computer failed, necessitating a manual docking by Dzhanibekov. Once the Soyuz trio had joined Berezovoy and Lebedev, the experiments began.

The Soviets thought that working with the French was more like the real thing. The experiments were more technically sophisticated and useful compared with

![]()

The Third Decade: 1981-1990

some of those carried on earlier Interkosmos missions. These included the French Echograph heart monitor, which was left on Salyut 7 after Chretien’s departure. During his stay aboard Salyut, during which he reached 360 km (224 miles) in the 51.6° orbit, and with the US Space Shuttle Columbia also in orbit, seven men were in space for the first time since 1969.

Soyuz T6’s successful mission ended in fine weather near Arkalyk at T + 7 days 21 hours 50 minutes 52 seconds, with Chretien highly impressed with the dynamics of re-entry, rather than his launch. Later, he was to criticise the Soviet planners for cramming too much into the work schedule and to remark that throughout the mission he never fully acclimatised to weightlessness.

Milestones

24 June 1982

85th manned space flight

51st Soviet manned space flight

44th Soyuz manned space flight

5th Soyuz T manned space flight

1st Soyuz international mission

1st manned space flight by a Frenchman

1st manned space flight by a West European