SOYUZ 1

|

Int. Designation |

1967-037A |

|

Launched |

23 April 1967 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 1, Site 5, Baikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan |

|

Landed |

24 April 1967 |

|

Landing Site |

65 km east of Orsk (fatal crash landing) |

|

Launch Vehicle |

R7 (11A511); spacecraft serial number (7K-OK) #4 |

|

Duration |

1 day 2 hrs 47 min 52 sec |

|

Callsign |

Rubin (Ruby) |

|

Objective |

Manned test flight of Soyuz 7K-OK variant; intended active craft for docking with passive “Soyuz 2’’ (cancelled) |

Flight Crew

KOMAROV, Vladimir Mikhailovich, 40, Soviet Air Force, pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: Voskhod 1 (1964)

Flight Log

Three months after the shocking Apollo 1 fire, what ostensibly began as a Soviet triumph, the flight of Soyuz 1, also ended in tragedy. The cause of the first fatal space mission was, like Apollo 1, over-confidence and bad workmanship. In fact, it could be called sheer foolhardiness. Four unmanned Soyuz test flights under the guise of the all-embracing Cosmos programme had failed. When he arrived at the Baikonur Cosmodrome, cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov must have been aware that he was laying his life on the line. But for what? It appears that Soyuz 1 was to attempt a propaganda coup to overshadow the US space programme still in mourning over Apollo 1. It was to fly into orbit and await the arrival of Soyuz 2, which would not only dock with it but would transfer two crewmen externally by EVA.

The space spectacular began with the launch of Soyuz 1, at 05:35 hrs local time. Komarov entered a 201-244 km (125-152 miles) orbit, with a unique manned inclination of 51°, and hit trouble. One solar panel did not deploy, and without necessary power many systems were degraded. Soyuz was the first manned spacecraft to carry solar panels. On another launch pad about 32 km (20 miles) away, another Soyuz booster was ready to launch Soyuz 2, carrying Valeriy Bykovsky, Yevgeniy Khrunov and Aleksey Yeliseyev. The latter two would be the EVA transfer crewmen. The launch was at first scrapped, then dramatically, plans were set in motion for an extraordinary rescue mission, during which the two Soyuz 2 EVA crewmen would pull out Soyuz 1’s stuck solar panel.

The Soyuz 2 trio went to bed to rest before the following day’s rescue bid. Meanwhile, attempts were made to terminate the Soyuz 1 mission. Komarov apparently tried to fire the retro-rocket on the sixteenth and seventeenth orbits, but

|

Komarov in training for Soyuz 1 |

probably had difficulty orienting the spacecraft. He succeeded on the eighteenth orbit and during the southbound re-entry towards an emergency landing zone, the spacecraft may have been out of full control, so much so that when the main landing parachute was deployed, it tangled.

Soyuz plummeted to the ground as Komarov awaited his fate. The capsule smashed into the ground, at T + 1 day 2 hours 47 minutes 52 seconds, at 08:22hrs on 24 April, causing a large crater and catching fire. Komarov had no ejection seat and had made the ultimate sacrifice. When the Soyuz 2 crew awoke, they were told the news. At the time, all the world knew was that Soyuz 1 was on a solo mission and its parachute had tangled. The full facts have never emerged and the planned Soyuz 2 mission was never officially confirmed by the Soviets until 1989, despite heaps of evidence that included photos of the two crews together.

Milestones

25th manned space flight 9th Soviet manned space flight 1st Soyuz manned flight 1st fatal space mission

During the recovery period in manned space flight following the twin tragedies of Apollo 1 and Soyuz 1, the final astro-flights of the X-15 programme took place – and suffered a tragedy of their own. On 17 October 1967, William “Pete” Knight, 38, of the USAF, flew X-15 aircraft number 3 on the eleventh astro-flight to an altitude of almost 86 km. The following month, on 15 November 1967, USAF pilot Michael Adams, 37, was killed in the crash of X-15 aircraft number 3 after attaining 81 km during the twelfth astro-flight. The final such flight occurred on 21 August 1968, with NASA civilian test pilot William Dana, 37, at the controls. The thirteenth astro-flight of the programme saw X-15 aircraft number 1 reach a peak altitude of 81 km.

|

Flight Crew

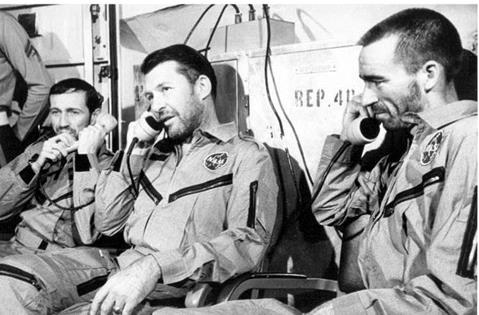

SCHIRRA, Walter Marty Jr., 45, USN, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: Mercury-Atlas 8 (1962); Gemini 6 (1965) EISELE, Donn Fulton, 38, USAF, command module pilot CUNNINGHAM, Walter, 36, civilian, lunar module pilot

Flight Log

Like a phoenix rising from the ashes, 623 days after the Apollo 1/204 spacecraft disaster, Apollo 7/205 lifted off from Pad 34 at Cape Kennedy, three minutes late, at 11: 03hrs on 11 October 1968, on a Saturn 1B. Redesigned, tested and re-tested, Apollo 7 was to conduct a thorough shakedown flight of the revised system before the USA could be confident again about going forward to the Moon. The 10 days 20 hours 9 minutes 3 seconds-long mission (which ended with the Command Module upside down but righted by buoyancy balloons, close to the recovery ship USS Essex), was brilliant, termed 101 per cent successful by NASA chiefs. Indeed so successful was it that the media, having nothing much to write about, zeroed in on the mood of the crew, thus misrepresenting the true nature of the flight.

True, the zealous commander Wally Schirra, the first to make three space flights, and his senior pilot Donn Eisele caught colds – probably during a hunting trip a few days before blast-off, thus introducing strict quarantine conditions for future crews. Schirra was distinctly very irritable at times during the mission, refusing to turn on in-flight television, making burns and re-entering with his crew not wearing their helmets. Schirra, Eisele and the healthy pilot Walt Cunningham, who did not catch a cold, had entered a 31.64° inclination orbit and separated from the S-IVB second stage, turned around and simulated the extraction of a Lunar Module (which was not flown) that would take place on Saturn V-boosted Moon flights, in what was called the

|

Eisele, Schirra and Cunningham receive a phone call from President Johnson |

transposition and docking manoeuvre. An added bonus of this 20-minute long station-keeping manoeuvre was superb photography showing the S-IVB flying right over the Cape and the nearby Kennedy Space Center.

The extremely busy flight plan – which to the chagrin of Schirra, several controllers tried to make flexible at rather short notice, leading the commander to announce that he would become the onboard flight director for the rest of the mission – included eight ignitions of the service propulsion system engine, so vital to lunar orbital insertion and trans-Earth injection burns. The longest of these burns lasted 66 seconds and enabled Apollo 7 briefly to reach an altitude of 430 km (267 miles). Inflight television shows were very well received on the ground and featured much lighthearted banter between the mission control team and the crew on orbit.

Milestones

26th manned space flight

17th US manned space flight

1st Apollo CSM manned flight

1st US three-crew space flight

1st space flight by a crewman on third mission