‘M EQUALS 1”

In spite of Young and Collins’ success, one particular aspect of Gemini XI caused the most worry: the desire to complete rendezvous and docking with the Agena-D target on their very first orbit! To be fair, ‘desire’ is probably the wrong word. The necessity for rendezvous and docking at such an early stage would be essential when an Apollo command and service module was approached by the ascent stage of a lunar module after the Moon landing.

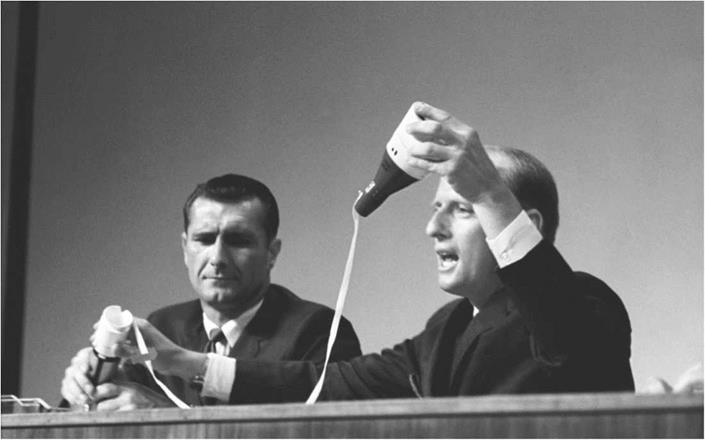

‘‘There was a lot of concern that it wasn’t going to be successful,’’ Gordon told Neil Armstrong’s biographer James Hansen. ‘‘For the Apollo application, the desire was to rendezvous as rapidly as possible because the lifetime of the LM’s ascent stage was quite limited in terms of its fuel supply.’’ To accomplish this first-lap rendezvous and docking, Gemini XI would have to meet a launch window barely two seconds long and Conrad and Gordon’s three days aloft would also feature a lengthy spacewalk, experiments … and the physical tethering of their spacecraft to the Agena target.

The purpose of the latter, said backup command pilot Neil Armstrong, was to ‘‘find out if you could keep two vehicles in formation without any fuel input or control action’’. Armstrong had been teamed with rookie astronaut Bill Anders to shadow Conrad and Gordon’s training regime and the foursome frequently found themselves in the Cape Kennedy beach house over the summer months of 1966, running through rendezvous and docking procedures, trajectories and flight plans. Before too many more years had passed, all four of them, on three separate missions, would apply this knowledge on flights to the Moon.

Conrad’s assignment to Gemini XI was inextricably linked to the mission’s demonstration of achieving high altitudes. In mid-1965, he learned of plans to fly the spacecraft around the Moon and, even when such a mission was rejected by Jim Webb and Bob Seamans, had pushed vigorously to use some of his Agena fuel to carry Gemini XI into a high orbit. Among the earliest champions of Conrad’s scheme were the scientists – flying to high altitude, he argued, would allow the astronauts to acquire high-resolution imagery of weather patterns and possibly benefit other experiments. Fears that the Van Allen radiation belts might scupper such a mission were allayed when Conrad despatched Anders – a qualified nuclear

|

|

engineer – to Washington to devise and argue ways of avoiding them. Indeed, radiation data gathered by Young and Collins on Gemini X had turned out to be barely a tenth of pre-flight estimates.

The plan to fly Gemini XI to high altitude thus approved, another of its key objectives – tethering the spacecraft to its Agena as a means of demonstrating better station-keeping – bore fruit. Under direction from NASA, McDonnell engineers recommended that a nylon or Dacron line no longer than about 50 m could produce a reasonable amount of cable tension. The station-keeping requirement for such an experiment quickly expanded, however, to encompass a means of inducing a form of artificial gravity. Ultimately, a 30 m Dacron tether was chosen for the task and the only serious concern was how Gemini XI could be freed from the Agena. It was decided to fire a pyrotechnic charge and, failing that, to snap a break line in the tether with a small separation velocity.

Particularly worrisome, though, was achieving rendezvous with the Agena on Conrad and Gordon’s very first orbital pass. (Within NASA, it was known as an ‘M = 1’ rendezvous.) This had been suggested several years earlier by Richard Carley of the Gemini Project Office, in response to Apollo managers’ concerns that such practice was necessary to provide a close approximation of lunar orbit rendezvous. During Gemini X, John Young had expended so much fuel that it seemed overly ambitious, but Flight Director Glynn Lunney eventually appeased naysayers that Mission Control could provide enough backup data on orbital insertion and manoeuvring accuracy that Conrad and Gordon would have all they needed to perform it. Still sceptical, William Schneider, deputy director for Mission Operations, bet the review board’s chairman James Elms a dollar that a first-orbit rendezvous could not be done economically.

Despite the greater success of Mike Collins in performing his EVAs on Gemini X, concerns remained. Practicing spacewalking techniques in a realistic environment had led, in mid-1966, to the adoption of‘neutral buoyancy’ – submerging fully-suited astronauts in a water tank – as the closest terrestrial analogue to the real thing. In his autobiography, Collins related its introduction in the closing weeks before his own mission, but had little time to spare practicing under such conditions. Gene Cernan, perhaps best-placed to observe the difficulties of EVA, was one of the first to undergo neutral buoyancy training, and found that it did indeed approximate his efforts in space.

Yet refining techniques also encompassed an astronaut’s body positioning and the inclusion of more practical aids, including handholds, shorter umbilicals (Young and Collins recommended a 9 m tether, rather than l5 m, to avoid entanglement, which was accepted) and better foot restraints in the Gemini adaptor section. This last proposal led to two suggestions from McDonnell – a spring clamp, like a pair of skis, and a ‘bucket’ type restraint – with NASA finally opting for the latter, which came to be nicknamed the ‘golden slippers’.

Rendezvous, docking, tethered station-keeping and spacewalking. . . and a full plate of 12 scientific experiments would thus fill Conrad and Gordon’s three days in space. Two of the experiments – Earth-Moon libration region imaging (S-29) and dim-light imaging (S-30) – were newcomers to Project Gemini, together with seven already-flown investigations into weather, terrain and airglow photography, radiation and microgravity effects, ion-wake measurements, nuclear emulsions and ultraviolet astronomy and a trio of technical objectives focusing on mass determination, night-image intensification and the evaluation of EVA power tools. By the end of August 1966, the Manned Spacecraft Center had announced that all of the experiments were ready to fly.

Elsewhere, preparations for Gemini XI had become closely entwined with those of the previous mission, Gemini X. The Titan II propellant tank for the latter had become corroded by leaking battery acid during transfer from Martin’s Denver to Baltimore plants in September 1965. It had been replaced with the tank originally allocated to Conrad and Gordon’s flight; the Gemini XI crew were correspondingly assigned the propellant tank previously earmarked for Gemini XII. This finally reached Baltimore for checkout and integration in January 1966.

Six months later, Conrad and Gordon’s Titan was in place on Pad 19 at Cape Kennedy. At around the same time, the Gemini spacecraft itself was hoisted into position and the hot weeks of August were spent connecting cabling and replacing some leaking fuel cell sections.

By this stage, Gemini XI’s launch date had slipped by two days to 9 September, but as the fuelling of its Titan II booster progressed, a minute leak was found in the first-stage oxidiser tank. Technicians quickly set to work rectifying the problem: a sodium silicate solution and aluminium patching plugged the leak and launch was rescheduled for the following day. That attempt, too, came to nothing, as Conrad and Gordon were en-route to Pad 19, when it was learned that their Agena-XI’s Atlas booster was experiencing problems with its autopilot. Hoping to resolve the glitch in time, the General Dynamics test conductor called a hold in the countdown to check it out.

The Atlas engineers out at Pad 14 reported that they were receiving faulty readings and were in the process of running checks to determine if the autopilot component needed replacement. Ultimately, the checks took too long to meet the launch window on 10 September and, after an hour of troubleshooting, the attempt to launch the two vehicles that day was called off. Another attempt, William Schneider announced, would be made on the 12th. It later became clear that the fault was caused by a fluttering valve, coupled with unusually high winds and an oversensitive telemetry recorder. Fortunately, none of the Atlas’ components needed to be changed and managers cleared the mission to fly.

Early on 12 September, Conrad and Gordon were sealed inside their spacecraft by Guenter Wendt’s closeout team at Pad 19. Despite a minor oxygen leak which required the reopening and resealing of Conrad’s hatch, the launch of their Agena – XI target went ahead on time at 8:05 am. Still, there was little time to waste, for Gemini XI had been granted barely two seconds in which to launch; its almost – impossibly-short ‘window’ dictated by the requirement to rendezvous with the Agena on the astronauts’ first orbit. It demonstrated, if nothing else, the growing maturity of America’s space effort. “Rocketeers of the Forties, Fifties and early Sixties,’’ wrote Barton Hacker and James Grimwood, ‘‘would have been aghast at the idea of having to launch within two ticks of the clock.’’

Aghast or not, Conrad and Gordon’s liftoff was perfect, coming at 9:42:26.5 am, just half a second into its mandated two-second launch period. Six minutes later, on the fringes of space, the two astronauts received the welcome news from Mission Control: their ascent and the performance of their Titan II had been ‘right on the money’ and they were cleared for their M = 1 rendezvous. To kick off its first sequence, just 23 minutes after launch, Conrad pulsed Gemini XI’s thrusters in a so – called ‘insertion-velocity-adjust-routine’ – or ‘Ivar’ – manoeuvre, correcting their orbital path and placing them on track to ‘catch’ the Agena, then 430 km away.

Conrad’s next manoeuvre was more tricky, occurring as it did outside of telemetry and communications range. At the appointed moment, he performed an out-ofplane manoeuvre of about one metre per second, then pitched Gemini XI’s nose 32 degrees ‘up’ from his horizontal flight plane. This completed, the two men activated their rendezvous radar and … just as predicted, they received an immediate electronic ‘lock-on’ with the Agena. By the time they re-established radio contact with the ground, they were just 93 km from their quarry.

Capcom John Young, seated at his console in Houston, sent final numbers through the Tananarive tracking station to the astronauts and, as Gemini XI neared the apogee of its first orbit, Conrad ignited the OAMS to produce ‘multi-directional’ changes – forward, ‘down’ and to the right – in support of the rendezvous’ terminal stage. All at once, less than 40 km away, the Agena flashed into view with orbital sunrise over the Pacific Ocean, almost blinding them as it did so. The two men scrambled for sunglasses and Conrad pulled his spacecraft to within 15 m of the target. Making landfall over California, and a little more than 85 minutes since launch, they had achieved the world’s quickest orbital rendezvous. Moreover, they still retained some 56 per cent of their fuel reserves. William Schneider lost his bet with James Elms, writing that ‘‘I never lost a better dollar’’.

‘‘Mr Kraft,’’ the jubilant astronauts called to Flight Director Chris Kraft, ‘‘would [you] believe M equals 1?’’ On 12 September 1966, he certainly did.