“TUMBLING END-OVER-END”

Gemini VIII was not aided by a distinct lack of available tracking stations across its flight path, which resulted in some very spotty communications with Mission Control. “We could communicate with Houston,” wrote Scott, “for only three five – minute periods every 90 minutes as we passed over secondary tracking stations.” Two ship-based stations were aboard the Rose Knot Victor and the Coastal Sentry Quebec, plus a land-based site in Hawaii. Shortly before one such loss of contact, at 6:35 pm, Armstrong and Scott were advised by Jim Lovell that, if problems arose whilst docked, they should deactivate the Agena and take control with the Gemini. “Just send in the command 400 to turn it off,” Lovell told them, “and take control with the spacecraft.” For now, however, the only problems seemed to be difficulties verifying that the Agena was receiving uplinked commands and a glitch with its velocity meter, used to specify the magnitude of a burn by its main engine.

Twenty-seven minutes after docking, Scott commanded the Agena to turn them 90 degrees to the right and Armstrong reported that the manoeuvre had “gone quite well”. His call came seconds before Gemini VIII passed out of radio range of the land-based Tananarive station in the Malagasy Republic. Working alone, the astronauts transmitted an electronic signal to start the Agena’s tape recorder. Shortly thereafter, their attitude indicators showed them to be in an unexpected, almost imperceptible, 30-degree roll. “Neil,” called Scott, “we’re in a bank’’.

Perhaps, they wondered, the Agena’s attitude controls were playing up or its software load was wrong. Since Gemini VIII’s OAMS was now switched off and both men could see the Agena’s thrusters firing, they reasoned that the target’s controls must be at fault. They could not have known at the time that one of their own OAMS thrusters – the No. 8 unit – had short-circuited and stuck in its ‘on’ position. Unaware, Scott promptly cut off the Agena’s thrusters, whilst Armstrong pulsed the OAMS in a bid to stop the roll and bring the combined spacecraft under control. For a while, his efforts succeeded.

After four tense minutes, the docked spacecraft slowed and steadied itself. Then, as Armstrong worked to reorient them into their correct horizontal position, the unwanted motions began again. . . much faster than before and, wrote Scott, ‘‘on all three axes’’. Perplexed, the men jiggled the control switches of the Agena, then of the Gemini, off and on, in a fruitless effort to isolate the problem. At around this time, Scott noticed that Gemini VIII’s own attitude propellant had dropped to just 30 per cent, clearly indicative of a problem with their own spacecraft. ‘‘It was clear,’’ Scott related, ‘‘we had to disengage from the Agena, and quickly.’’

Undocking presented its own problems, not least of which was the very real risk that the two rapidly rotating vehicles could impact one another. However, Scott, demonstrating an intuitive test pilot’s awareness of the importance of recording all pertinant data, pre-set the Agena’s recording devices such that ground controllers would still be able to remotely command it. ‘‘I knew that, once we undocked, the rocket would be dead,’’ he wrote. ‘‘No one would ever know what the problem had been or how to fix it.’’ Scott’s prompt action saved the Agena and preserved it for subsequent investigations and tasks.

Still out of radio contact with the ground, Armstrong moved onto the next step of the flight rules and undocked from the Agena. He then fired a long burst of Gemini VIII’s translational thrusters to pull away, only to discover that the spacecraft, now free, began to spin more wildly, in roll, pitch and yaw axes. It was now much worse than before, because the stuck-on No. 8 thruster was no longer turning the entire combination, only the Gemini. High above south-east Asia, they came within range of the Coastal Sentry Quebec, which received Scott’s urgent radio transmission at 6:58 pm: “We have serious problems here… we’re tumbling end-over-end. We’re disengaged from the Agena.’’

Aboard the ship, Capcom Jim Fucci acknowledged the call and enquired as to the nature of the problem. Both men were relieved to hear Fucci’s voice. “He was an old NASA hand,’’ wrote Scott, “very experienced.” Quickly, yet with characteristic calmness, Armstrong reported that he and Scott were “in a roll and we can’t seem to turn anything off. . . continuously increasing in a left roll’’. Fucci duly passed the

|

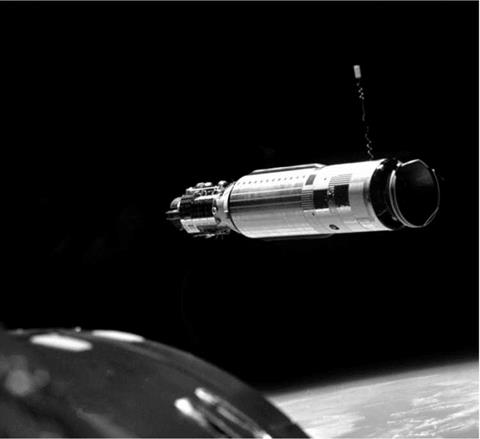

Gemini VIII during rendezvous activities with the Agena. |

report over to Houston: Gemini VIII was suffering “pretty violent oscillations”. The three-way conversation with Mission Control meant that it was some seconds before Flight Director John Hodge picked up all of the details; Fucci having to repeat that “he’s in a roll and he can’t stop it”.

Armstrong quickly threw circuit breakers to cut electrical power and hence the flow of propellant to the attitude thrusters, including the No. 8 unit. However, with no friction or counterfiring thruster to stop it, the spinning continued. At its worst, it reached 60 revolutions per minute. Everything in the cabin – checklists, flight plans, procedures charts – were hurled around by the centrifugal force. The unfiltered Sun flashed in the astronauts’ windows with alarming regularity, said Scott, “like a strobe light hitting us in the face’’.

Such a rotation rate placed the men at serious risk of physically blacking out and, indeed, both had difficulties reading their instruments properly. “It was rather like the feeling you get as a kid when you twist a jungle rope round and round and then hang on it as it spins and unfurls,’’ wrote Scott. “In space, it was not a good feeling.’’ Physician Chuck Berry would later note that the astronauts experienced two conditions brought on by the rapid rotation: a complete loss of orientation caused by the effects on their inner ears (the ‘coriolis effect’), coupled with ‘nystagmus’, an involuntary rhythmic motion of the eyes.

The incessant rotation and the depletion of Gemini VIII’s attitude propellant had already alerted Armstrong and Scott to a problem with their own spacecraft, but at the time they did not know that the short circuit in the OAMS had caused the No. 8 thruster to become stuck ‘on’ and caused the rapid drop in fuel. Even had they known, there would have been no time to ponder it. Armstrong’s responsibility as the command pilot was to ensure the safety and success of the mission. Scott’s spacewalk, docked activities with the Agena and most of the experiments were now off the agenda; the safe return of the crew was paramount.

Armstrong decided that his only available course of action was to use Gemini VIII’s 16 re-entry controls. It was easier said than done. The re-entry control switch was in the most awkward position imaginable, directly above Armstrong’s head, and, worse, was on a panel with around a dozen toggles. ‘‘With our vision beginning to blur,’’ wrote Scott, ‘‘locating the right switch was not simple.’’ Fortunately, both men had carried their years of test-piloting experience into the astronaut business and intuitively knew every switch, literally, with their eyes closed. ‘‘Neil knew exactly where that switch was without having to see it,’’ Scott continued, but admitted ‘‘reaching above his head. . . while at the same time grappling with the hand controller… was an extraordinary feat.’’

The effort to reduce the spacecraft’s rates to zero with the re-entry controls, though ultimately successful, consumed 75 per cent of the fuel. ‘‘We are regaining control of the spacecraft slowly,’’ Armstrong reported, as the spinning stopped within 30 seconds. The flight, however, was over. Mission rules decreed that the reentry controls, once activated, would require an immediate return to Earth at the next available opportunity. Just ten hours into its three-day mission, Gemini VIII was on its way home.