Onward and Upward

TRAGEDY

The failure of the first Agena-D target vehicle on 25 October 1965 left the Gemini effort in a quandary. Its role in the following year’s rendezvous and docking missions was crucial, yet its reliability had been brought into serious doubt. Efforts to resolve its woes spanned four months and the first few weeks after the failure were spent identifying the cause. Investigators quickly focused on the Agena’s engine. By November, a ‘hard-start’ hypothesis – in which fuel was injected into the combustion chamber ahead of the oxidiser, effectively causing it to ‘backfire’ – had been generally accepted by the engineers. However, this problem was itself deeply rooted in NASA’s original specification for the Agena-D to be able to restart itself up to five times during a single mission.

In order to achieve multiple restarts, oxidiser began flowing first, then a pressure switch restricted fuel flow until a given amount of oxidiser had reached the combustion chamber. This had the advantage of enhancing the engine’s startup characteristics, but was also extremely wasteful, with numerous instances of oxidiser leaks. As a result, oxidiser was often expended before fuel. In an effort to rectify this wastage problem, engine subcontractor Bell Aerosystems removed the pressure switch, allowing fuel to enter the combustion chamber ahead of the oxidiser. However, the investigative panel for the Agena-D speculated that fuel in the chamber – perhaps in considerable quantities – might have caused the engine to backfire when the oxidiser arrived, resulting in an explosion.

Meanwhile, in mid-November, a two-day symposium on hypergolic rocket ignition at altitude convened to discuss the failure and identify corrective actions. The data from the accident implied that oscillations and mechanical damage had been induced after engine ignition and temperature drops pointed towards a fuel spillage of some sort. When the Agena’s electrical circuitry failed, the engine stopped, but a valve responsible for managing fuel tank pressures remained open. As the fuel stopped flowing, pressures built up inside the tanks, which ruptured and destroyed the vehicle. Although the symposium was unsatisfied that this represented

the definitive cause of the accident, it had little other data upon which to base its judgements. One of its recommendations was that future Agena-D engines should be modified and tested at simulated altitudes closer to those at which it would operate: 76 km. (Previously, it had only been tested at simulated altitudes of 34 km.)

In response, Lockheed formed a Project Surefire Engine Development Task Force to carry out the modification programme, which continued to arouse debate until the week before Gemini Vlff’s scheduled March 1966 launch. By that time, the crew assigned to a subsequent mission, Gemini IX, had lost their lives in a blaze which nearly claimed their spacecraft, too. Civilian Elliot See, a deeply religious former General Electric pilot who had performed engine testing before coming to NASA, was paired with Air Force Major Charlie Bassett – “a terrific stick-and-rudder man,” according to Gene Cernan – to fly a three-day mission and practice rendezvous, docking and spacewalking.

At 7:35 am on 28 February 1966, the men and their backups, Cernan and Tom Stafford, took off from Ellington Field near Houston in a pair of T-38s and flew in tandem to McDonnell’s St Louis plant. “Prime and backup were not allowed to fly in the same airplane,’’ wrote Mike Collins, “lest a crash wipe out the entire capability in one specialty.’’ In other words, in Gemini IX’s case, See could fly with anyone but Stafford and Bassett with anyone but Cernan. Their schedule called for them to spend ten days in St Louis, practicing rendezvous procedures in the simulator, as well as viewing their just-completed Gemini IX spacecraft. Weather conditions in St Louis that morning were bad, with low cloud, poor visibility, rain and snow flurries, and at 8:48 am Lambert Field airport – located 150 m from the McDonnell plant – prepared to support two instrument-guided landings. lt was standard practice to rely upon instruments under such appalling weather conditions.

The two sleek T-38s – tailnumbered ‘NASA 901’ (See and Bassett) and ‘NASA 907’ (Stafford and Cernan) – descended through the murky clouds at 8:55 am, directly above the centreline of the south-west runway, far too low and flying too fast to land. Stafford, who had been concentrating on remaining in position on See’s right wing, decided to ascend and attempt a flyaround. However, See inexplicably announced his intention to enter a tight turn and make another approach. Normally careful, considered and judicious, it has been speculated over the years that he wanted to beat the backup crew to the runway. If this was indeed the case, it surely demonstrated that See had the competitive nature typical of an astronaut. Sadly, good luck was not on his side that day.

Stafford was surprised as See’s T-38 disappeared from view, exclaiming to Cernan: ‘‘Goddamn! Where the hell’s he going?’’ Breaking through the clouds, heading directly for the corrugated-iron Building 101, which contained Gemini lX, See realised he could not land successfully. He lit his afterburners, broke hard right and pulled back on the stick, but at 8:58 am the T-38 grazed the top of the building, gashed open the roof – losing a wing as it did so – and cartwheeled into a nearby parking lot, whereupon it exploded.

lnside Building 101, McDonnell foreman Domien Meert watched aghast from his desk in the subassembly room as a sheet of flame flared across the now-exposed ceiling. Workers dived for cover under benches as honeycomb shards from the T-38’s

|

|

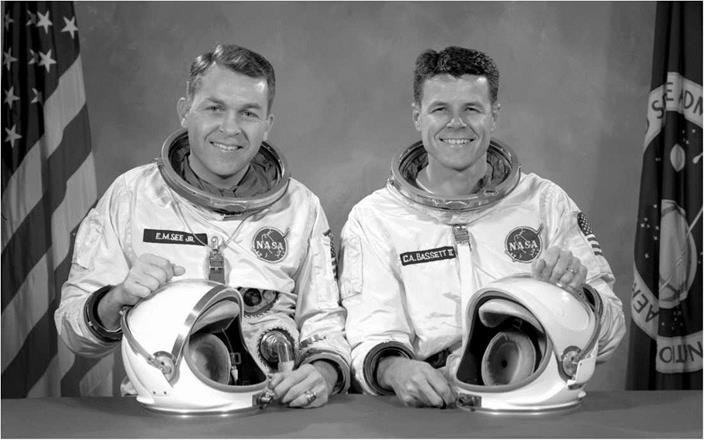

![]() The original Gemini IX crew, Elliot See (left) and Charlie Bassett. Scheduled for a three-day mission in May 1966, they were both killed in St Louis just 11 weeks before launch.

The original Gemini IX crew, Elliot See (left) and Charlie Bassett. Scheduled for a three-day mission in May 1966, they were both killed in St Louis just 11 weeks before launch.

shattered wing hit the Gemini X spacecraft, still under construction. Elliot See, who had been thrown from the fuselage, was found dead in the parking lot, his parachute half-opened, while Charlie Bassett – one of the most promising of the third group of astronauts, selected in October 1963 – had been decapitated. His severed head was later retrieved from the rafters of the very building in which his spacecraft was being readied for flight.

Stafford and Cernan were oblivious to the tragedy. They were simply ignored by air traffic controllers, left to their own devices and, wrote Cernan, “annoyed that the tower was being so vague in its communications”. Eventually, with a near-empty fuel gauge pushing him close to declaring an emergency, Stafford set NASA 907 down on the runway without incident and turned onto the taxiway. He was puzzled by an odd question from the tower: “Who was in NASA 901?” When Stafford told them that the Gemini IX prime crew was aboard the other T-38, he was advised that McDonnell Aircraft had “a message” for him. Minutes later, after opening his canopy, Stafford was told by James McDonnell himself that See and Bassett had both been killed.

The men’s remains, wrote Cernan, were unrecognisable and their identification was not helped by the fact that all four astronauts had placed their NASA badges and personal papers in a baggage pod aboard See and Bassett’s T-38 before leaving Houston. Only by checking with the men who were still alive was it possible to determine which ones had died.

It seemed impossible to imagine 28 February 1966 as a day for miracles, but it was to say the very least fortuitous that no deaths were sustained on the ground. If See had been a little lower at the moment of impact, he would have hit Building 101 in a head-on collision, destroying Gemini IX and potentially killing hundreds of McDonnell staff who were skilled in the art of manufacturing spacecraft The United States’ plan to reach the lunar surface before the end of the decade would have evaporated.

Later that afternoon, James McDonnell climbed onto the roof to survey the damage. Next day, his company’s 37,000 employees returned to work and, as planned, on 2 March, Gemini IX was loaded aboard a C-124 transport aircraft and flown to Cape Kennedy. At around the same time, the entire astronaut corps gathered at Arlington National Cemetery to watch as the remains of 38-year-old Elliot McKay See Jr and 34-year-old Charles Arthur Bassett II were laid to rest.

NASA immediately created a seven-man investigative board, chaired by Al Shepard, which examined every parameter and detail relating to See and Bassett’s tragic final flight. The T-38, it was found, was in perfect operational order and the men’s physical and psychological state was fine. Their flying abilities, on paper at least, were exemplary and both had renewed their instrument flying certificates within the last six months. The appalling weather was certainly a contributory factor in the disaster, but the board’s final conclusion that pilot error was to blame did not surprise Deke Slayton.

“Of all the guys in the second group of astronauts,” he wrote, “Elliot was the only one I had any doubts about. I had flown with him and the conclusion was just that he wasn’t aggressive enough. Too old-womanish. . . he flew too slow – a fatal

problem in a plane like the T-38, which will stall easily if you get below about 270 knots.” Slayton had named See as Neil Armstrong’s pilot on the Gemini V backup crew, but had not felt confident to keep the pairing together for Gemini VIII, particularly since the latter would feature a lengthy EVA. “He wasn’t in the best physical shape,’’ Slayton wrote, adding that “I didn’t think he was up to handling an EVA. I made him commander of Gemini IX and teamed him up with Charlie Bassett – who was strong enough to carry the two of them.’’

Neil Armstrong, who worked with See on Gemini V, has said little about his qualifications as an astronaut, but certainly found it difficult to blame his comrade for his own death. “It’s easy to say… what he should have done was gone back up through the clouds and made another approach,’’ Armstrong told biographer James Hansen. “There might have been other considerations that we’re not even aware of. I would not begin to say that his death proves the first thing about his qualification as an astronaut.’’

Regardless, years later, Slayton would admit that he had allowed himself to “get sentimental’’ about giving See a mission and that, ultimately, it was a bad call. Within hours of the tragedy, he had telephoned Tom Stafford to tell him that he and Cernan were now the Gemini IX prime crew. Three weeks later, Jim Lovell and Buzz Aldrin were named as their backups. It is interesting that the deaths of See and Bassett proved pivotal in deciding the identities and shaping the futures of the men who would someday be the first to set foot upon the Moon. By backing up Gemini IX, for example, Aldrin eventually wound up as pilot on the very last Gemini mission. Slayton admitted in his autobiography that without this twist of fate, it would have been “very unlikely’’ that Aldrin would have gone on to join the first Apollo lunar landing crew. Indeed, Neil Armstrong and Dave Scott, set to fly Gemini VIII on 16 March 1966, would become the only Gemini crew who would both someday walk on the lunar surface.

For Armstrong, his astronaut career would be the culmination of a lifetime of aviation which had carried him to the edge of the atmosphere in rocket-propelled aircraft, into the world’s first spaceflying corps and almost into suborbital space aboard a revolutionary machine called ‘Dyna-Soar’.