CHANGED PLANS

Gordo Cooper and Pete Conrad had flown the equivalent of a minimum-duration lunar flight and, indeed, one of them would tread its dusty surface in a little over four years’ time. Apart from stiff joints, heavy beards, a tendency to itch and an aroma, like that of McDivitt and White, which seemed somehow ‘different’ from everyone else on the recovery ship, they were fine. Cooper, whose heart averaged 70 beats per minute, had come through Gemini V in better shape than Faith 7. After eight days in a half-sitting, half-lying position, both men managed to do some deep-knee bends aboard the recovery helicopter, hopped onto the deck of the Lake Champlain without assistance and walked without wobbling.

They had, NASA flight surgeons determined, come through the mission less fatigued than the Gemini IV crew. This was at least partly because Cooper and Conrad got around six hours’ sleep per night during the early portion of their flight. However, their weight loss was perplexing: Cooper had lost 3.4 kg and Conrad 3.8 kg whilst aloft. They had, admittedly, only eaten 2,000 calories per day, rather than the scheduled 2,700, and drank their quotas of water, but both regained the lost weight within days. Still, neither exhibited signs of orthostatic hypotension and Chuck Berry asserted that ‘‘we’ve qualified man to go to the Moon’’.

Those plans received an abrupt setback on 25 October 1965.

When Wally Schirra and Tom Stafford were assigned to Gemini VI, they were told by Deke Slayton that their two-day mission would feature the world’s first rendezvous with a Lockheed-built Agena-D target. Their backups, Gemini 3 fliers Gus Grissom and John Young, had been picked because Slayton ‘‘wanted a veteran backup crew to help with training’’. In his autobiography, Stafford would recall that Young sat actively through simulations with them, whereas Grissom was often absent, racing cars or boats. After three years working on Gemini, Grissom now had his sights set on commanding the first Apollo mission. Following Gemini VI would come Gemini VII, sometime early in 1966, flown by Frank Borman and Jim Lovell and backed-up by Ed White and Mike Collins. The decision to fly the first rendezvous mission ahead of the long-duration 14-day flight had come about because of ongoing Agena problems; Charles Mathews wanted assurances that, if anything went wrong on Gemini VI, there would be enough time to resolve it before resuming rendezvous practice from Gemini VIII onwards.

The first Gemini-Agena Target Vehicle (GATV), numbered ‘5001’, was shipped to Cape Kennedy in May 1965, purely as a non-flying test article, and three months later its successor – ‘5002’ – was officially earmarked for Schirra and Stafford’s mission. However, doubts over its reliability lingered. Its main engine, some felt, could not be trusted to execute manoeuvres with a docked Gemini and, although Schirra lobbied for it to go ahead, opposition within NASA to firing it was strong.

|

Next, Schirra pushed for a firing of the Agena’s less powerful secondary propulsion system, although this was not initially incorporated into the Gemini VI flight plan. To be fair, rendezvous techniques were very much in their infancy in 1965, as demonstrated by the unsuccessful attempt of Jim McDivitt to station-keep with the second stage of his Titan II. Buzz Aldrin, however, was a rendezvous specialist, having completed a doctorate in the field before becoming an astronaut, and he joined forces with Dean Grimm of NASA’s Flight Crew Support Division to plan a so-called ‘concentric rendezvous’ technique for Gemini-Agena missions.

Their plan was for the target to be launched, atop its Convair-built Atlas rocket, into a 298 km circular orbit, after which Schirra and Stafford would be despatched into a lower, ‘faster’, elliptical orbit. ‘‘Two hundred and seventy degrees behind the Agena,’’ wrote Stafford, ‘‘you’d make a series of manoeuvres that would eventually raise the orbit of the Gemini to a circular one below the Agena. Then you’d glide up below the Agena on the fourth revolution. At that time the crew would make a series of manoeuvres to an intercept trajectory, then break to station-keeping and docking.’’ This docking would occur over the Indian Ocean, some six hours into the mission, after which Schirra and Stafford would remain linked for seven hours and return to Earth following their battery-restricted two-day flight. The astronauts wanted to relight the Agena’s engine whilst docked, but NASA managers vetoed it as too ambitious.

During their training at McDonnell’s St Louis plant during the last half of 1965, the astronauts practiced manoeuvres again and again, plotting them on boards. In total, they did more than 50 practice runs and spent many hours rehearsing the actual docking exercise with the Agena-D in a Houston trainer. ‘‘Housed in a six – story building,’’ wrote Schirra, ‘‘it consisted of a full-scale Gemini cockpit and the docking adaptor of the Agena. They were two separate vehicles in an air-drive system that moved back and forth free of friction. We exerted control in the cockpit with small thrusters, identical to those on the spacecraft. We could go up and down, left and right, back and forth. The target could be manoeuvred in those planes as well, though it was inert. It would move if we pushed against it, just as we assumed the Agena would do in space.’’

On one such training session, Schirra hosted Vice-President Hubert Humphrey in the pilot’s seat. The vice-president asked Schirra if their voices could be heard from outside the trainer. When Schirra replied that, no, it was sound-proofed, Humphrey asked if Schirra minded him having a ten-minute nap. When Humphrey awoke, he asked Schirra to tell him what had happened so that he could tell the people outside. ‘‘I was a fan of Hubert Humphrey from that day on,’’ wrote Schirra.

Although barred from naming Gemini VI, Schirra sketched a design for a patch which he and Stafford could wear. It featured the constellation of Orion, which, navigationally, was to play an important part in the rendezvous. ‘‘The patch would be six-sided,’’ Schirra wrote, ‘‘since six was the number of our mission. Orion also appears in the first six hours of right ascension in astronomical terms, a quarter of the way around the celestial sphere.’’

In anticipation of this dramatic mission, processing of Gemini VI’s flight hardware ran smoothly. In April 1965, its launch vehicle, GLV-VI, became the first Titan to be erected in the new west cell at Martin’s vertical testing facility in Baltimore, Maryland. The rocket’s two stages arrived in Florida at the beginning of August and were placed into storage. Schirra and Stafford’s spacecraft arrived at about the same time and was hoisted atop a timber tower for electronic compatibility testing with GATV-5002. Such exercises would later become standard practice in readying Gemini-Agena missions. It was the last Gemini to run on batteries, thus limiting Schirra and Stafford to no more than 48 hours in space, although, by September, NASA was pushing for just one day if all objectives were completed. Even Gemini VI’s experiments – two rendezvous tests (in orbital daytime and nighttime), one medical, three photographic and one passive – were considered secondary to the proximity operations with the Agena. Said Schirra: “On my mission, we couldn’t afford to play with experiments. Rendezvous [was] significant enough!’’

However, so much reliance was being placed on the radar, the inertial guidance platform and the computer that Grimm and Aldrin found the pilot’s role was seriously impaired; if these gadgets failed, wrote Barton Hacker and James Grimwood, so too would the whole mission. Grimm persuaded McDonnell managers to rig up a device which could allow the astronauts to simulate trajectories, orbital insertion and spacecraft-to-Agena rendezvous paths. As a result, Schirra and Stafford were able to participate in no fewer than 50 simulations, conferring with Aldrin on techniques and procedures. Stafford would also recall the admirable efforts of‘Mr Mac’ himself – James McDonnell, founder of the aerospace giant which bore his name – who, upon learning that the astronauts needed more time on the training computers, complied. ‘‘Mr Mac was always behind the programme,’’ Stafford wrote. In fact, he and Schirra invited McDonnell to dinner on the night before the Agena’s, and their own, planned liftoff.

Early on 25 October, out at the Cape’s Pad 14, a team from General Dynamics oversaw the final hours of the Atlas-Agena countdown. The Atlas booster, tipped with the slender, pencil-like Agena, was scheduled to fly at precisely 10:00 am. Meanwhile, Al Shepard, by now the chief astronaut, woke the Gemini VI crew and joined them for breakfast and suiting-up. Schirra, struggling to give up smoking, lit up a Marlborough during the ride to Pad 19. He felt, wrote Stafford, ‘‘he could survive a twenty-four-hour flight without getting the shakes’’. One and a half kilometres to the south, General Dynamics launch manager Thomas O’Malley pressed the firing button for the Atlas-Agena at 10:00 am and the first half of the GTA-VI mission was, it seemed, underway. The countdown had gone without a hitch and, with 140 flights behind it since 1959, the performance of the Agena was unquestioned. The plan was for it to separate from the Atlas high above the Atlantic, then fire its own 7,200 kg-thrust engine over Ascension Island to boost itself into orbit. The complex orchestra of synchronised countdowns would culminate at 11:41 am with Schirra and Stafford’s own liftoff to initiate the rendezvous. Then, things began to go wrong.

The Agena apparently separated from the Atlas, but seemed to wobble, despite the efforts of its attitude controls to stabilise it. Right on time, downlinked telemetry confirmed that its engine had indeed ignited. . . and then nothing more was heard. It

|

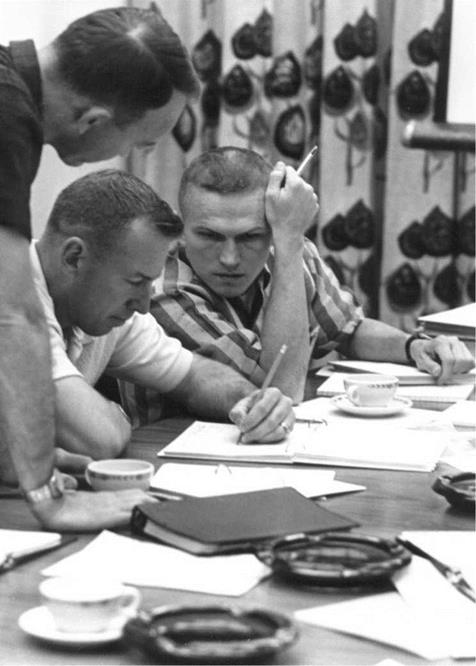

Tom Stafford (standing) and Wally Schirra suit-up. |

had reached an altitude of some 230 km and was 872 km downrange of Cape Kennedy. Fourteen minutes after launch, it should have appeared to tracking radars in Bermuda, but was nowhere to be seen; except, that is, for what appeared to be five large fragments. Aboard Gemini VI, the astronauts, fully-suited, aboard a fully – fuelled rocket and ready to go, were puzzled. “Maybe it’s the tracking station,” Schirra surmised. “Let’s wait for Ascension Island.’’ As time dragged on, their countdown was held at T-42 minutes, but no sign of the Agena was forthcoming. Ascension Island saw nothing. “No joy, no joy,’’ came an equally dismal report from the Carnarvon station in Australia and NASA’s public affairs officer Paul Haney was forced to tell listeners at 10:54 am that the target vehicle was almost certainly lost. The Gemini VI launch was scrubbed.

In fact, problems had become apparent very soon after the Atlas-Agena left its pad. At 10:06 am, just six minutes into its ascent, Jerome Hammack at the Pad 14 blockhouse was convinced that something was wrong. So too was the Air Force officer in charge of the launch. Although early analysis of the partial telemetry data gave little inkling of what had happened, an explosion seemed the most plausible explanation. “Later investigation,’’ wrote Tom Stafford, “concluded that the Agena had exploded, thanks to an oxidiser feed sequence that had been changed.’’

In Houston, Flight Director Chris Kraft, together with Bob Gilruth and George Low, surveyed the damage. It was clear that if a rendezvous mission was to take place at all, a delay of several weeks simply to identify the cause of the accident would be unavoidable. “And if it turns out to be a major design failure in the Agena,’’ Time magazine drearily told its readers, “the Gemini programme is in deep trouble.’’ Critics argued that the Agena, with a satisfactory track record as a missile, had been extensively modified for its Gemini role and many of these modifications had never been tested in space. A disappointed Schirra and Stafford were quietly extracted from their capsule, to be told by Al Shepard: “Boys, what we need is a good party.’’ It was the perfect answer, to cheer everyone up, so the three men, together with Grissom and Young, headed off into town.

“For a day of so,’’ wrote Deke Slayton, “we thought about recycling Agena 5001, the ground test bird that hadn’t ever come up to specs.’’ However, a lengthy investigation into what went wrong with the 5002 target would still need to be carried out, the results of which would not be clear for weeks. Moreover, a new Agena would not be ready until early 1966. A perfect alternative, however, was on the horizon. Immediately after the Agena’s loss, Frank Borman overheard a conversation between McDonnell officials Walter Burke and John Yardley: the former suggested launching Gemini VII as Schirra and Stafford’s ‘new’ rendezvous target. A study of sending Geminis up in quick succession had been done months earlier and seemed an ideal option, but for one detail. Burke sketched his idea onto the back of an envelope, but Borman doubted the practicality of installing an inflatable cone onto the end of Gemini VII to permit a physical docking. Moreover, George Mueller and Charles Mathews dismissed the entire idea, since it would require the launch of both Geminis within an impossibly tight two-week period.

Other managers thought it could be done. Joseph Verlander and Jack Albert proposed stacking a Titan II and placing it into storage until another had been

assembled. The Titan’s engine contractor, Aerojet-General, had stipulated that the vehicle must remain upright, but this could be achieved with a Sikorsky S-64 Skycrane, after which the entire rocket could be kept on the Cape’s disused Pad 20. Immediately after the first Gemini’s launch from Pad 19, the second Titan stack could be moved into position and sent aloft, conceivably, within five to seven days. The plan, however, held little appeal and received little enthusiastic response, with most attention focused on swapping the 3,553 kg Gemini VI for the 3,670 kg Gemini VII, thereby making good of a bad situation by at least using the Titan II combination already on the pad to fly Borman and Lovell’s 14-day mission.

In the next few days, as this was discussed in the higher echelons of NASA management, it became evident that if the two spacecraft were swapped, the earliest that Borman and Lovell could be launched would be 3 December. However, if the Gemini VII spacecraft were to prove too heavy for the GLV-VI Titan, a delay until around 8 December would become necessary to erect the more powerful GLV-VII. It was then envisaged to launch Schirra and Stafford to perform their rendezvous mission with another Agena sometime in February or early March 1966.

As these plans crystallised, Burke and Yardley posed their joint-flight idea to Bob Gilruth and George Low, who could find few technical obstacles, with the exception, perhaps, that the Gemini tracking network might struggle to handle two missions simultaneously. Even Mathews, when presented with the option, could find few problems, although Chris Kraft’s initial response was that they were out of their minds and it could not be done. Then, having second thoughts, he asked his flight controllers for their opinions, and the most that they could object to was that the Gemini tracking network might struggle to handle two missions. Kraft called his deputy, Sigurd Sjoberg, to discuss the possibility further with the Flight Crew Operations Directorate, headed by Deke Slayton. News filtered down, eventually, to Schirra and Stafford, who heartily endorsed it.

The prospects for Burke and Yardley’s plan steadily brightened when it became clear that the heavy Gemini VII – which, after all, was intended to support a mission seven times longer than Gemini VI – could not be lofted into orbit by Schirra and Stafford’s Titan: it simply was not powerful enough to do the job. Yet the question of tracking two vehicles at the same time remained. Then, another possibility was aired. Could the tracking network handle the joint mission if Gemini VII were regarded as a passive target for Gemini VI? Borman and Lovell would launch first, aboard Gemini VII, and control of their flight would proceed normally as the Gemini VI vehicle was prepared to fly.

As soon as controllers were sure that Gemini VII was operating satisfactorily, they would turn their attention to sending up Gemini VI; in the meantime, Borman and Lovell’s flight would be treated like a Mercury mission, wrote Deke Slayton, “where the telemetry came to Mission Control by teletype, letting the active rendezvous craft have the real-time channels that were available’’. This mode would continue until ‘Gemini VI-A’ – so named to distinguish it from the original, Agena – rendezvousing Gemini VI mission – had completed its tasks and returned to Earth. After Schirra and Stafford’s splashdown, Borman and Lovell would again become the focus of the tracking network.

Before NASA Headquarters had even come to a decision, the rumour mill had already informed the press, some of whom reported the possibility of a dual-Gemini spectacular. On 27 October, barely two days after the Agena failure, Jim Webb, Hugh Dryden, Bob Seamans and other senior managers discussed the idea and George Mueller asked Bob Gilruth to confirm that it would work. The answer was unanimously in the affirmative and Webb issued a proposal for the joint flight to the White House. He informed President Johnson that, barring serious damage to Pad 19 after the Gemini VII launch, Schirra and Stafford’s Titan could be installed, checked out and flown within days to rendezvous with Borman and Lovell. Johnson, residing at his ranch in Austin, Texas, approved the plan on 28 October and his press secretary announced it would fly in January 1966. At NASA, however, December 1965 was considered more desirable.

As October turned to November, preparations gathered pace. Aerojet-General set to work implementing steps by which, contrary to its stipulation, the Titans could be handled in a horizontal position, whilst the Air Force destacked GLV-VI from the pad and placed it in bonded storage under plastic covers at the Satellite Checkout Facility. On 29 October, Gemini VII’s heavy-lift Titan was erected on Pad 19. Guenter Wendt’s first reaction when he saw the short, nine-day Gemini VI-A pad- preparation schedule, was “Oh, man, you are crazy!’’ The Gemini VI-A spacecraft, meanwhile, was secured in a building on Merritt Island. Although Schirra and Stafford’s mission would essentially not change, that of Borman and Lovell was slightly adjusted to circularise its orbit and mimic the Agena’s flight path as closely as possible. Elsewhere, the Goddard Space Flight Center was busy setting up and altering tracking station layouts to enable simultaneous voice communications with both capsules.

At one point, ideas were even banded around for an EVA, in which Lovell and Stafford would spacewalk to each other’s Geminis and land in a different craft. However, Borman had little interest in such capers. His target was a 14-day mission and he had no desire to do anything that would compromise it. Also, he wished to use the new ‘soft’ suits that could be doffed in flight. If a spacewalk were to be added to the flight plan, he and Lovell would have to wear conventional space suits, which would make a 14-day mission an even greater chore. In any case, for Lovell and Stafford to exchange places they would have to detach and reconnect their life – support hoses in a vacuum, leaving them with nothing but their backup oxygen supplies for a while. The bottom line for Borman was that whilst an external transfer might have made great headlines, ‘‘one little slip could have lost the farm’’. Coupled with the fact that Stafford, as one of the tallest of the New Nine, sometimes had difficulty egressing from the capsule during ground tests, the decision was taken to eliminate EVA from the joint mission.