“EIGHT DAYS OR BUST”

Although Gemini V, the first to carry and utilise fuel cells for electrical power, had long been planned to fly for seven or even eight days, the success of its predecessor and the performance of Jim McDivitt and Ed White had emboldened NASA to move up their estimates for the first lunar landing from 1970 to 1969 and, perhaps, said Joe Shea, as early as mid-1968. Both Gemini IV astronauts would remain very much part of the unfolding action: White was named within weeks to the backup command slot for Gemini VII, an assignment rapidly followed by the coveted senior pilot’s seat on the maiden Apollo voyage. McDivitt, too, would go on to great things: commanding Apollo 9, a complex engineering and rendezvous flight to pave the way for the first Moon landing. He would even be offered, but would refuse, the chance to walk on the lunar surface himself.

First, though, came the adulation. After an initial Houston reception, they headed for Chicago, where a million people greeted them and showered them in tickertape along State Street and Michigan Avenue. This was followed, in Washington, DC, by another parade down Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol, receptions in the Senate, meetings with foreign diplomats and even a free trip to Paris to upstage the appearance of Yuri Gagarin and a mockup of Vostok 1 at 1965’s Air Show. It is unknown to see such scenes as tickertape parades for astronauts today and, perhaps, the only ones in the foreseeable future may be for the men and women who return to the Moon or become the first to tread the blood-red plains of Mars.

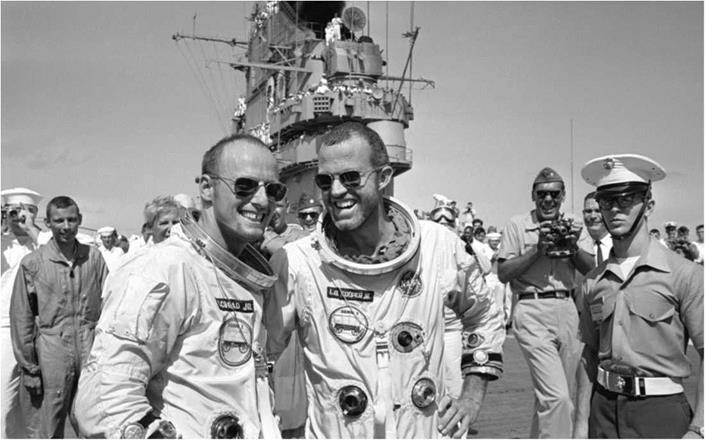

In the Sixties, however, every mission was heroic. Moreover, despite the appalling workload and the inevitable strain the astronaut business placed on marriages and families, every man who left Earth’s atmosphere was a fully-fledged hero. Not for nothing did Gerry and Sylvia Anderson name their five Thunderbird heroes after five of the heroes of the Mercury Seven: Alan, Virgil, John, Scott and Gordon. For one of those heroes, Gordo Cooper, and his rookie pilot, Pete Conrad, the reality in the build-up to their mission was one of exhausting 16-hour workdays, plus weekends, and a tight schedule to launch on 1 August 1965, eight weeks after McDivitt and White splashed down. Cooper and Conrad and their backups, Neil Armstrong and Elliot See, had only been training since 8 February, giving them less than six months to prepare for the longest mission yet tried. “We realised they needed more time,” wrote Deke Slayton. “I went to see George Mueller to ask him for help and he delayed the launch by two weeks.”

Despite the pressure, Cooper and Conrad found time to give some thought to names for their spacecraft, even though NASA had officially barred them from doing so. Due to its pioneering nature, the two men wanted to call Gemini V ‘The Conestoga’, after one of the broad-wheeled covered wagons used during the United States’ push westwards in the 18th and 19th centuries. Their crew patch, in turn, would depict one such wagon, emblazoned with the legend ‘Eight Days or Bust’. This was quickly vetoed by senior managers, who felt it suggested a flight of less than eight days would constitute a failure, and Conrad’s alternative idea – ‘Lady Bird’ – was similarly nixed because it happened to be the nickname of the then-First Lady, wife of President Johnson. Its possible misinterpretation as an insult could provoke unwelcome controversy which NASA could ill-afford. The astronauts, however, would not be put off and Cooper pleaded successfully with Jim Webb to approve the Conestoga-wagon patch, although the administrator greatly disliked the idea. The duality of the word ‘bust’ as denoting both a lack of success and the female breasts did not help matters, either. . .

Preparations for Gemini V had already seen Conrad gain, then lose, the chance to make a spacewalk. According to a January 1964 plan, the Gemini IV pilot would depressurise the cabin, open the hatch and stand on his seat, after which an actual ‘egress’ would be performed on Gemini V (Conrad’s mission), a transfer to the back of the spacecraft and retrieval of data packages on Gemini VI and work with the Agena-D target vehicle on subsequent flights. Following the Voskhod 2 success, however, plans for a full egress were accelerated and granted to Ed White. The result: instead of ‘Eight Days or Bust’, Gemini V would come to be described by Cooper and Conrad as ‘Eight Days in a Garbage Can’; they would simply ‘exist’ for much of their time aloft, to demonstrate that human beings could survive for at least the minimum amount of time needed to get to the Moon and back. (The maximum timespan for a lunar mission, some 14 days, would be an unwelcome endurance slog earmarked for the Gemini VII crew.)

Yet the Conestoga mission did have its share of interesting gadgets: it would be the first Gemini to run on fuel cells, would carry the first production rendezvous radar and was scheduled to include exercises with a long-awaited Rendezvous Evaluation Pod (REP). Originally, it was also intended to fly the newer, longer-life OAMS thrusters, although these were ready ahead of schedule and incorporated into Gemini IV. Only weeks after Cooper, Conrad, Armstrong and See began training, on 1 April 1965 fabrication of the Gemini V capsule was completed by McDonnell,

|

|

tested throughout May in the altitude chamber and finally delivered to Cape Kennedy on 19 June. Elsewhere, GLV-5 – the Titan booster assigned to launch the mission – was finished in Baltimore, accepted by the Air Force and its two stages were in Florida before the end of May. Installation on Pad 19 followed on 7 June, the day of McDivitt and White’s splashdown, and Gemini V was mounted atop the Titan U on 7 July. Five days later, the last chance for an EVA on the mission and, indeed, on Geminis VI and VII, was rejected by NASA Headquarters. There seemed little point in repeating what White had already done and, further, Cooper and Conrad, not wishing to be encumbered by their space suits for eight days, had campaigned vigorously for greater comfort in orbit by asking to wear helmets, goggles and oxygen masks. The launch of Gemini V was scheduled for 19 August.

It would be a false start. Thunderstorms ominously approached the Cape, rainfall was copious and a lightning strike caused the spacecraft’s computer to quiver. The latter, provided by IBM, had caused concern on Gemini IV and, this time around, had been fitted with a manual bypass switch to ensure that the pilots would not be left helpless again. The attempt was scrubbed with barely ten minutes remaining on the countdown clock and efforts to recycle for another try on 21 August got underway. On this second attempt, no problems were encountered. Aboard Gemini V, Cooper turned to Conrad. “You ready, rookie?’’ Conrad, white as a sheet, replied that he was nervous. Surely the decorated test pilot who had flown every supersonic jet the Navy owned wasn’t scared? Conrad milked the silence in the cabin for a few seconds, then burst out laughing. “Gotcha!” he said with his trademark toothy grin. “Light this son-of-a-bitch and let’s go for a ride!’’ And ride they did. At 8:59:59 am, Cooper and Conrad were on their way.

Ascent was problematic when noticeable pogo effects in the booster jarred the men for 13 seconds, but smoothed out when the second stage ignited and were minimal for the remainder of the climb. Six minutes after launch, as office workers across America snoozed away their Saturday morning, Gemini V perfectly entered a 163-349 km orbit. Nancy Conrad wrote that her late husband compared the instant of liftoff to “a bomb going off under him, then a shake, rattle and roll like a ’55 Buick blasting down a bumpy gravel road – louder than hell’’.

Hitting orbit made Cooper the first man to chalk up two Earth-circling missions. (Gus Grissom, of course, had piloted a suborbital flight on Liberty Bell 7, before commanding the orbital Gemini 3.) However, Gemini V would shortly encounter problems. The flight plan called for the deployment of the 34.5 kg REP, nicknamed ‘The Little Rascal’, from the spacecraft’s adaptor section, after which Cooper would execute a rendezvous test, homing in on its radar beacon and flashing lights. Before the REP could even be released, as Gemini V neared the end of its first orbit, Conrad reported, matter-of-factly, that the pressure in the fuel cells was dropping rapidly from its normal 58.6-bar level. An oxygen supply heater element, it seemed, had failed. Nonetheless, as they passed over Africa on their second orbit, Cooper yawed the spacecraft 90 degrees to the right and, at 11:07 am, explosive charges ejected the REP at a velocity of some 1.5 m/sec. Next, the flight plan called for Gemini V to manoeuvre to a point 10 km below and 22.5 km behind the REP, although much of this work was subsequently abandoned. However, Chris Kraft’s ground team was becoming increasingly concerned as the fuel cell pressures continued to decline and when a pressure of 12.4 bars was reached this was insufficient to operate the radar, radio and computer. Kraft had little option but to tell the astronauts to cancel their activities with the pod.

It seemed likely that a return to Earth would be effected and Kraft ordered four Air Force aircraft to move into recovery positions in the Pacific for a possible splashdown some 800 km north-east of Hawaii. A naval destroyer and an oiler in the region were also ordered to stand by. Keenly aware of the situation, Cooper radioed that a decision needed to be made over whether to abort the mission or power down Gemini V’s systems and continue, to which Kraft told him to shut off as much as he could. All corrective instructions proved fruitless: neither the automatic or manual controls for the fuel cell’s oxygen tank heater would function. Nor could the heater itself, located in the adaptor section, be accessed by the crew. Cooper and Conrad even manoeuvred their spacecraft such that the Sun’s rays illuminated the adaptor, in the hope that it might stir the system back to life. It was all in vain.

By now, most of their on-board equipment – radar, radio, computer and even some of the environmental controls – had been shut down and, as Gemini V swept over the Atlantic on its third orbital pass, there was much speculation that a re-entry would have to be attempted before the end of the sixth circuit, since its flight track thereafter would take it away from the Pacific recovery area. Then, as the astronauts passed within range of the Tananarive tracking station in the Malagasy Republic, off the east coast of Africa, Cooper reported that pressures were holding at around 8.6 bars, suggesting, Kraft observed, that “the rate of decrease is decreasing”. As he spoke, the oxygen pressures dropped still lower, to just 6.5 bars, and fears were high that if they declined much further, Gemini V would need its backup batteries to support another one and a half orbits and provide power for re-entry and splashdown. The astronauts were asked to switch off one of the fuel cells to help the system and as they entered their sixth orbit the pressures levelled-out at 4.9 bars.

Capcom Jim McDivitt asked Cooper for his opinion on going through another day under the circumstances. “We might as well try it,’’ replied Cooper, but Kraft remained undecided. After weighing all available options, including the otherwise satisfactory performance of the cabin pressure, oxygen flow and suit temperatures, together with the prestige to be lost if the mission had to be aborted, he and his control team emerged satisfied that oxygen pressures had stabilised at 4.9 bars. If there were no more drops, Gemini V would be fine to remain in orbit for a ‘drifting flight’, staying aloft just long enough to reach the primary recovery zone in the Atlantic, sometime after its 18th orbit. Admittedly, with barely 11 amps of power, only a few of the mission’s 17 experiments could be performed, but Kraft felt ‘‘we were in reasonably good shape. . . we had the minimum we needed and there was a chance the problem might straighten itself out’’. As Cooper and Conrad hurtled over Hawaii on their fifth orbit, he issued a ‘go’ for the mission to proceed.

With the reduced power levels, the REP, which kept the spacecraft company up until its eighth orbit, was useless for any rendezvous activities. ‘‘That thing’s right with us,’’ Cooper told Mission Control during their sixth circuit of Earth. ‘‘It has been all along – right out in back of us.’’ Two orbits later, Conrad turned Gemini V a full 360 degrees, to find that the pod had re-entered the atmosphere to destruction. Nonetheless, Gemini V’s radar did successfully receive ranging data from the REP for some 43 minutes.

As the mission entered its second day, circumstances improved and oxygen pressures climbed. “The morning headline,” Kraft radioed the astronauts on 22 August, referring to a newspaper, “says your flight may splash down in the Pacific on the sixth orbit.” Having by now more than tripled that number of orbits, Conrad replied that he was “sorry” to disappoint the media. Despite the loss of the REP, on their third day aloft Cooper conducted four manoeuvres to close an imaginary ‘gap’ between his spacecraft and the orbit of a phantom Agena-D target. This ‘alternate’ rendezvous had been devised by the astronaut office’s incumbent expert, Buzz Aldrin. Cooper fired off a short burst from the aft-mounted OAMS thrusters to lower Gemini V’s apogee by about 22 km, then triggered a forward burn to raise its perigee by some 18 km and finally yawed the spacecraft to move it onto the same orbital plane as the imaginary target. One final manoeuvre to raise his apogee placed Gemini V in a co-elliptical orbit with the phantom Agena. Were it a ‘real’ target, he would then have been able to guide his spacecraft through a precise rendezvous. Such exercises would prove vital for Gemini VI, which was scheduled to hunt down a ‘real’ Agena-D in October 1965, and one of the greatest learning experiences, said Chris Kraft, ‘‘is being able to pick a point in space, seek it out and find it’’.

Notwithstanding the successes, the glitches continued. On 25 August, two of the eight small OAMS thrusters jammed, requiring Cooper to rely more heavily on their larger siblings and expend considerably more propellant than anticipated. It was at around this time that Gemini V broke Valeri Bykovsky’s five-day endurance record and Mission Control asked Cooper if he wanted to execute ‘‘a couple of rolls and a loop’’ to celebrate; the laconic command pilot, however, declined, saying he could not spare the fuel and, besides, ‘‘all we have been doing all day is rolling and rolling!’’ When the record of 119 hours and six minutes was hit, Kraft blurted out a single word: ‘‘Zap!’’ Gordo Cooper, with an additional 34 hours from Faith 7 under his belt, was now by far the world’s most flown spaceman. His response when told of the milestone, though, was hardly historic: ‘‘At last, huh?’’

The dramatic reduction of available propellant made the last few days little more than an endurance run. Kraft told the astronauts to limit their OAMS usage as much as possible and many of their remaining photographic targets – which required them to manoeuvre the spacecraft into optimum orientations – had to be curtailed. Still, a range of high-quality imagery was acquired. The hand-held 70 mm Hasselblad flew again to obtain photographs of selected land and near-shore areas and, of its 253 images, some two-thirds proved useful in post-mission terrain studies. These included panoramas of the south-western United States, the Bahamas, parts of south-western Africa, Tibet, India, China and Australia. Images of the Zagros Mountains revealed greater detail than was present in the official Geological Map of Iran. Cooper and Conrad also returned pictures of meteorological structures – including the eye of Hurricane Doreen, brewing to the east of Hawaii – together with atmospheric ‘airglow’. In addition, they took pictures of the Milky Way, the zodiacal light and selected star fields. Other targets included two precisely-timed Minuteman

missile launches and infrared imagery of volcanoes, land masses and rocket blasts.

The scientific nature of many of these experiments did not detract – particularly in the eyes of the Soviet media – from the presence of a number of military-sponsored investigations. Cooper and Conrad’s flight path carried them over North Vietnam 16 times, as well as 40 times over China and 11 times over Cuba, prompting the Soviet Defence Ministry’s Red Star newspaper to claim that they were undertaking a reconnaissance mission. The situation was not helped by President Johnson’s decision, whilst the crew was in orbit, to fund a major $1.5 billion Air Force space station effort, known as the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL). Among the actual military experiments undertaken by Gemini V were observations of the Minuteman plume and irradiance studies of celestial and terrestrial backgrounds, together with tests of the astronauts’ visual acuity in space to follow up on reports that Cooper had made after his Faith 7 mission. Large rectangular gypsum marks had been laid in fields near Laredo, Texas, and Carnarvon, Australia, although weather conditions made only the former site visible.

Cardiovascular experiments performed during the mission would reveal that both men lost more calcium than the Gemini IV crew, although principal investigator Pauline Beery Mack expressed reluctance to predict a ‘trend’, since “a form of physiological adaptation may occur in longer spaceflight”. Medically, Chuck Berry’s main concerns were fatigue and his advice was that they get as much sleep as possible. ‘‘I try to,’’ yawned Conrad at one stage, ‘‘but you guys keep giving us something to do!’’ All in all, they managed between five and seven hours’ sleep at a time and expressed little dissatisfaction with Gemini V’s on-board fare: bite-sized, freeze-dried chunks of spaghetti and meatballs, chicken sandwiches and peanut cubes, rehydratable with a water pistol. An accident with a packet of shrimp, though, caused a minor problem when it filled the cabin with little pink blobs. Conrad even tried singing, out of key, to Jim McDivitt at one point.

Years later, Conrad would recall that the eight-day marathon was ‘‘the longest thing I ever had to do in my life’’. He and Cooper had spent the better part of six months training together, so ‘‘didn’t have any new sea stories to swap with one another… there wasn’t a whole lot of conversation going on up there’’. Nancy Conrad would recall her late husband describing how the confined cabin caused his knees to bother him – their sockets felt as if they had gone dry – and that he would have gone ‘‘bananas’’ if asked to stay aloft any longer. (Ironically, on two future missions, Conrad would stay aloft for much, much longer. . . but on those occasions, his tasks would include a couple of meandering trots around the lunar surface and floating inside a voluminous space station.) He found it hard to sleep, hard to get comfortable and the failures meant he and Cooper spent long periods simply floating with nothing to do. After the flight, he told Tom Stafford that he wished he had taken a book, and this gem of experience would be noted and taken by the crew assigned to fly the 14-day mission.

Nancy Conrad described Cooper’s irritation at losing so much of his mission. He was far from thrilled that the two main tasks for Gemini V, rendezvous and long – duration flight, were becoming little more than ‘‘learning-curve opportunities’’ and suggested throwing an on-board telescope in the Cape Kennedy dumpster when it twice refused to work. Later, when the spacecraft was on minimum power and the astronauts were still expected to keep up with a full schedule, Cooper snapped “You guys oughtta take a second look at that!” As for physical activity, he grimaced that his only exercise was chewing gum and wiping his face with a cleansing towel.

On the ground, Deke Slayton was concerned that such an attitude would not help Cooper’s reputation with NASA brass. Indeed, Gemini V would be his final spaceflight and, although he would later complain bitterly about ‘losing’ the chance to command an Apollo mission, some within the astronaut corps would feel that Cooper’s performance and strap-it-on-and-go outlook had harmed his career. Tom Stafford was one of them. ‘‘Gordo… had a fairly casual attitude towards training,’’ he wrote, ‘‘operating on the assumption that he could show up, kick the tyres and go, the way he did with aircraft and fast cars.’’

To spice matters up still further, worries about the fuel cells continued to plague Gemini V’s final days. Their process of generating electricity by mixing hydrogen and oxygen was producing 20 per cent too much water, Kraft told Conrad, and there were fears that the spacecraft was running out of storage space. This water excess might back up into the cells and knock them out entirely. In order to create as little additional water as possible, the astronauts powered down the capsule from 44 to just 15 amps and on 26 August Kraft even considered bringing them home 24 hours early, on their 107th orbit. However, by the following day, the water problem abated, largely due to the crew drinking more than their usual quota and urinating it into space, and a full-length mission seemed assured.

Eitherway, they had long since surpassed Bykovsky’s Vostok 5 record. In fact, by the time Cooper and Conrad splashed down, they would have exceeded the Soviets on several fronts: nine manned missions to the Reds’ eight, a total of 642 man-hours in space to their 507 and some 120 orbits on a single mission to their 81. At last, after eight years in the shadows – first Sputnik, then Gagarin, Tereshkova, Voskhod 1 and Leonov – the United States was pulling ahead into the fast lane of the space race. When it seemed that Gemini V might come home a day early and miss the scheduled Sunday 29 August return date, mission controllers in Houston even played the song ‘Never on Sunday’, together with some Dixieland jazz.

The astronauts also had the opportunity on the last day of the mission to talk to an ‘aquanaut’, Aurora 7 veteran Scott Carpenter, who was on detached duty to the Navy. Carpenter, who had broken his arm in a motorcycle accident a year before and been medically grounded by NASA, was partway through a 45-day expedition in command of Sealab II, an underwater laboratory on the ocean floor, just off the coast of La Jolla, California. The Sealab effort, conceived jointly by the Navy and the University of California’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography, sought to discover the capacity of men to live and work effectively at depth. In doing so, Carpenter became the first person to place ‘astronaut’ and ‘aquanaut’ on his career resume. Yet, unlike Cooper and Conrad, his chances of returning to space were nonexistent. He had not impressed senior NASA managers with Aurora 7 and, indeed, the partial success of an operation to repair the injury to his arm meant he would remain grounded anyway. He resigned from NASA in early 1967.

The music, the chat with Carpenter and even Conrad’s dubious singing did little

to detract from the uncomfortable conditions aboard the capsule. As they drifted, even with coolant pipes in their suits turned off, the two men grew cold and began shivering. Stars drifting past the windows proved so disorientating that they put covers up. Sleep was difficult. Chuck Berry had wired Conrad with a pneumatic belt, a blood-pressure-like cuff, around each thigh, which automatically inflated for two minutes of every six throughout the entire mission. The idea was that, by impeding blood flow, it forced the heart to pump harder and gain its much-needed exercise. Berry felt that if Conrad came through Gemini V in better physical shape than Cooper, who did not wear the belt, a solution may have been found for ‘orthostatic hypotension’, the feelings of lightheadedness and fainting felt by some astronauts after splashdown.

For the two astronauts, that splashdown could not come soon enough. By landing day, 29 August, their capsule had become cluttered with rubbish, including the litter of freeze-dried shrimp, which had escaped earlier in the mission. The appearance of Hurricane Betsy over the prime recovery zone prompted the Weather Bureau to recommend bringing Gemini V down early and Flight Director Gene Kranz agreed to direct the Lake Champlain to a new recovery spot. At 7:27:43 am, Cooper fired the first, second, third, then fourth OAMS retrorockets, then gazed out of his window. It felt, he said later, as if he and Conrad were sitting ‘‘in the middle of a fire’’. Since it was orbital nighttime, they had no horizon and were entirely reliant upon the cabin instruments to control re-entry. In fact, Gemini V remained under instrument control until they passed into morning over Mississippi.

Cooper held the spacecraft at full lift until it reached an altitude of 120 km, then tilted it into a bank of 53 degrees; whereupon, realising that they were too high and might overshoot the splashdown point, he slewed 90 degrees to the left to create more drag and trim the error. Although experiencing a dynamic load of 7.5 G after eight days of weightlessness, the astronauts did not, as some had feared, black out. The parachute descent was smooth. No oscillations were evident and the 7:55:13 am splashdown, though 170 km short of the planning spot, was soft. As would later be determined, the computer had been incorrect in indicating that they would overshoot. A missing decimal point in a piece of uplinked data had omitted to allow for Earth’s rotation in the time between retrofire and splashdown. In fact, Cooper’s efforts to correct the false overshoot had progressively drawn them short of the recovery zone. ‘‘It’s only our second try at controlling re-entry,’’ admitted planning and analysis officer Howard Tindall. ‘‘We’ll prove yet that it can be done.’’

Gemini V had lasted seven days, 22 hours, 55 minutes and 14 seconds from its Pad 19 launch to hitting the waves of the western Atlantic and the crew was safely aboard the Lake Champlain by 9:30 am. With the exception of the failed REP rendezvous, and one experiment meant to photograph the target, all of Cooper and Conrad’s objectives had been successfully met. Yet more success came when Chuck Berry realised that, despite the days of inactivity with little exercise aboard the capsule, the astronauts were physiologically ‘back to normal’ by the end of August, clearing the way for Frank Borman and Jim Lovell to attempt a 14-day endurance run on Gemini VII in early 1966. First, though, Wally Schirra and Tom Stafford would fly Gemini VI for one or two days in October and complete the first rendezvous with an

Agena-D target. The mission – or, rather, missions – that would follow would snatch victory from the jaws of defeat and set aside another obstacle on the path to the Moon. But not before suffering a major setback of its own.