RECORD BREAKERS

The men’s physical and psychological wellbeing was of paramount concern. Fear of dehydration led physicians to remind them regularly to drink water – at least 1.2 litres a day – because their space suits’ cooling systems evaporated perspiration as it formed, thus increasing the loss of body fluids. Their food sounded appealing, but in reality its freeze-dried or dehydrated nature and the need to mix it with water and knead it until mushy, lessened its attractiveness. Still, beef pot roast, banana pudding, fruitcake and even a Roman Catholic treat of fish on Friday for McDivitt formed the basis of their four-day diet. They would also recall space sandwiches, “covered with waxy-tasting stuff to keep the crumbs from getting in your eyes, ears and nose’’, undoubtedly less desirable than Gus Grissom’s corned beef option. Spaghetti dishes, too, required rehydration by water pistol. “You cut the other end with a pair of scissors,’’ McDivitt recalled later, “put the tube in your mouth and squeezed the stuff.’’ Indeed, it provided much-needed sustenance, rather than desirable food.

Sanitation on such a long mission presented its own obstacles. Both men would return to Earth with four-day beards, neither having been able to shave, and ‘washing’ was effected with little more than small, damp cloths to mop their faces. Urine was dumped overboard, while faeces were stored in self-sealing bags with disinfectant pills. Living amidst all of this, they had 11 experiments to perform. Photography of selected land and near-shore regions for geological, geographical and oceanographical studies undoubtedly proved the most enjoyable and 207 images were acquired with a hand-held 70 mm Hasselblad 500-C camera. Among the most

|

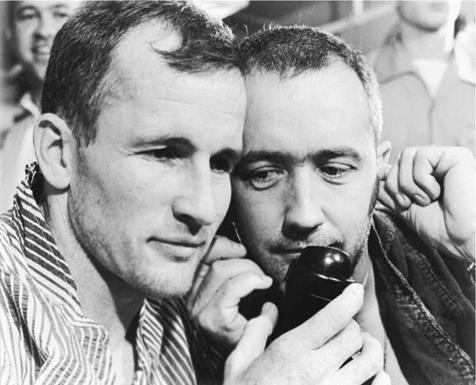

White (left) and McDivitt speak to President Johnson after the flight. |

visually stunning were terrain images of north-western Mexico, the south-western United States, North Africa, the Bahamas and the Arabian peninsula, although weather photographs captured a broad range of meteorological phenomena, including cellular cloud patterns, layers of clouds in tropical disturbances, lines of cumulus covering the oceans and vast thunderheads. The Hasselblad also proved essential for a series of two-colour images of Earth’s limb, part of efforts to better define the daylit horizon with red and blue filters.

Elsewhere, a proton-electron spectrometer monitored the radiation environment encountered through the South Atlantic Anomaly region (an intense ‘pocket’ of Earth’s ionosphere) and a tri-axis magnetometer measured the magnitude and direction of the local geomagnetic field with respect to the spacecraft. Five dosimeters, scattered throughout Gemini IV, kept watch on radiation levels, particularly as McDivitt and White passed through the South Atlantic Anomaly. In other areas, a bone demineralisation experiment revealed the first signs of mass loss in astronauts exposed to long periods of weightlessness and both men agreed that systematic exercise programmes were a necessity on future flights. A bungee cord was provided, but even the super-fit White found that his desire to do strenuous work dwindled as the mission dragged on, perhaps due to lack of sleep.

Rest, it seemed, was a precious commodity and one which both McDivitt and White found hard to capture. During their 33rd orbit, two days into the mission, Gus Grissom told them that they had a relatively free 18 hours and advised them to get as much sleep as they could. He recommended that one of them unplug their headset entirely to ensure uninterrupted rest. At other times, the chatter was incessant. Grissom radioed to McDivitt on one occasion that his son’s Pee Wee League team, the Hawks, had defeated the Pelicans 3-2, and to White that his son had scored a hit in a Little League game. The astronauts talked to their wives, with McDivitt asking Pat if she was behaving herself and assuring her that “about all I can do is look out the window’’. White’s wife, the second Pat, commented that her husband seemed to be “having a wonderful time’’ on his EVA and advised him to drink plenty.

On their third day in orbit, the spacecraft’s IBM computer failed. It was supposed to have been updated during a pass over the United States and McDivitt was asked to switch it off and then back on again. However, he quickly discovered that he could not bring it back to life. Attempts to try different switch positions came to nothing. Ironically, only days earlier, IBM had published an advert in the Wall Street Journal, praising its computers as being so reliable that even NASA used them. The failure caused no great alarm, but it did mean that a computer-controlled re-entry would now be impossible and, in Gemini IV’s final orbits, Chris Kraft advised McDivitt that ground computers would help steer the spacecraft for him. As the 7 June return to Earth neared, the astronauts were told to brace themselves for an 8 G re-entry, which McDivitt, only days short of his 36th birthday, joked was “too much for an old man like me!’’

Although in good spirits, neither astronaut felt particularly comfortable. McDivitt told Chuck Berry that he felt “pretty darn woolly’’, needed a bath, and, when asked if there was anything else he needed, replied “Yeah, my computer!’’ After the pre-retrofire checklist, the Hawaii capcom counted them down to the OAMS ‘fail-safe’ burn at 11:56 am, which reduced Gemini IV’s perigee to just 80 km. The burn lasted two minutes and 41 seconds and used most of the remaining propellant. They jettisoned the equipment section shortly before making contact with the station in Mexico. McDivitt initiated the retrofire one second late. The capsule hit the ocean at 12:12:11 pm, some four days and two hours since liftoff. Their splashdown point was about 725 km east of Cape Kennedy and, despite being slightly long of its target, McDivitt and White were soon joined by frogmen and landed by helicopter on the deck of the aircraft carrier Wasp at 1:09 pm. Their sturdy spacecraft was also safely aboard the carrier by 2:28 pm.

Re-entry, McDivitt recounted later, was the prettiest part of the flight. ‘‘We saw pink light coming up around our spacecraft,’’ he said. ‘‘It got oranger, then redder, then green. It was the most beautiful sight I have ever seen.’’ The two men were described by Time as being heavily bearded and sweaty, their faces lined with fatigue, although that did not prevent McDivitt from letting out a whoop of joy. Medical examinations revealed that White, whose normal heart rate was 50 beats per minute, registered 96 whilst lying supine aboard the Wasp; this climbed to 150 when the table was tilted slightly. McDivitt, on the other hand, was found to have flecks of caked blood in his nostrils, probably attributable to the dryness of his mucous membranes after inhaling pure oxygen for so long.

Both men had lost weight – McDivitt shed 1.8 kg, White some 3.6 kg – although, summing up, Chuck Berry was more than satisfied that they were in good physical shape. Gemini IV and the condition of its astronauts promised, he said, “to knock down an awful lot of straw men. We had been told that we would have an unconscious astronaut after four days of weightlessness”. Clearly, that was not the case. As if further demonstration were needed, a day after splashdown, still aboard the Wasp, White noticed a group of marines and midshipmen having a tug-of-war and joined them for 15 minutes. Although ‘his’ team lost, the astronaut certainly appeared to be the epitome of health and fitness.

On the day of Gemini IV’s splashdown, the two men received congratulations from President Johnson, together with joint promotions from majors to lieutenant-colonels and NASA’s Distinguished Service Medal. Elsewhere, the University of Michigan awarded them both with newly-created honorary doctorates in astronautical science. Also promoted to the same rank, Johnson announced, were Gordo Cooper and Gus Grissom. ‘‘I can hardly get used to people calling me ‘Colonel’,’’ wryly observed Ed White. ‘‘I know in a million years, I’ll never get used to people calling me ‘Doctor’!’’ (The spot promotions may have been at least partly inspired by a remark made by Grissom. When asked if there were any differences between American astronauts and Soviet cosmonauts, Gruff Gus had replied: ‘‘Yeah. They get promoted and we don’t!’’)

Before McDivitt and White could take their new titles, however, they both needed to take a shower. After four days without washing, White wondered what all the fuss was about. ‘‘I thought we smelled fine,’’ he said of his and McDivitt’s ‘distinct aroma’. ‘‘It was all those people on the carrier that smelled strange!’’