RISKY ENDEAVOUR

The Voskhod 1 fliers were still in orbit when the first of the calamitous events of October 1964 took place. Indeed, when Komarov requested a one-day extension to the mission, he was cryptically refused by Korolev, who quoted Hamlet with the words ‘‘There is more in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy’’. This has been taken by some historians as a veiled hint at Khrushchev’s removal from office and, perhaps, that Voskhod 1 was originally intended to fly a somewhat longer mission. After a full day aloft, during which time Yegorov took pulse and respiration measurements, Feoktistov checked Voskhod’s equipment and atmosphere and Komarov evaluated the spacecraft’s orientation system, the time came for the fiery plunge to Earth.

According to Asif Siddiqi, the extreme shortness of Yegorov and Feoktistov’s training regime was reflected in their reactions to weightlessness. “Within two or three hours of the launch,’’ he wrote, “both began to experience disorientation in space. Yegorov felt as if he was bent over face-downward, while Feoktistov actually felt he was upside down. Although the sensations apparently did not impair their ability to work, both suffered these feelings throughout the entire length of the mission. . . an anomaly that had not been detected on any of the earlier Soviet space missions. Both cosmonauts also felt dizzy when they moved their heads sharply. It seems that Yegorov had been more afflicted, with his unpleasant sensations peaking about seven hours after launch. . .’’

Shortly after 9:00 am Moscow Time on 13 October, Komarov was advised of the landing instructions and completed the orientation of Voskhod and the firing of its retrorocket. Indications that everything did not go entirely smoothly were, however, relieved by an electrical signal from the spacecraft, which confirmed that the main capsule had separated from the instrument section. At 10:26 am, a tracking station in the Caucasus picked up the signal and followed Voskhod 1 as it hurtled over the Caspian Sea, sped high above the fishing port of Aralsk in south-western Kazakhstan and finally touched down 312 km north-east of Kustanai. Further electrical signals confirmed that the parachute hatch jettisoned properly, but for an anxious Sergei Korolev the key concern was whether the parachutes themselves had deployed. Airman Mikhailov, aboard an Ilyushin-14 some 40 km east of Marevka, confirmed that he saw two parachute canopies. . . then, thankfully, the welcome sight of the capsule on the ground with the three men, alive and well, waving at him.

Landing occurred at 10:47 am, completing a mission of scarcely a few minutes more than 24 hours, and the three cosmonauts were helicoptered to Kokchetav and thence to Kustanai and finally Tyuratam, arriving late in the afternoon. Komarov, the only ‘real’ cosmonaut on the crew, was described as looking tired, but the two ‘invalids’, Feoktistov and Yegorov, were in good condition and high spirits. Plans for the men to speak to Khrushchev, mysteriously, were postponed when it became apparent that he had returned from his dacha in Pitsunda to Moscow. All attempts to call him at his office in the capital were unsuccessful; only later would it become apparent that as Voskhod plummeted Earthward, so Khrushchev’s premiership had plummeted to its own ignominious end.

In their first conversations with the physicians, Feoktistov and Yegorov would describe their first – and only – experience of weightlessness: the former said that he found conditions not at all unpleasant and the latter, while admitting to feeling unwell during the first few orbits, recovered thereafter. Khrushchev remained uncontactable and, indeed, Marshal Sergei Rudenko was ordered to fly back to the capital immediately, delaying the cosmonauts’ report to the State Commission until the next day. In his diary, Nikolai Kamanin noted his concern that ‘‘something unusual was happening in Moscow’’. The cosmonauts’ post-flight visit to Red

Square was cancelled and their first meeting with the Soviet leader did not come until 19 October, nearly a full week after their landing. That leader was not Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev, but Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev.

The three-strong crew, Time magazine told its readers on 23 October, “was a sure promise of multi-man space stations”, adding that “none of these feats have yet been accomplished by the lagging US space programme”. Indeed, at the beginning of the second decade of the human exploration of space, following their loss of the Moon race, the Soviets would become the first to establish a true foothold in the heavens with a long-term orbital base called Salyut. ft was a remarkable achievement that would, by the end of the 20th century, see cosmonauts spending more than a year apiece in space, and despite the harsh economic downturn after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russian expertise continues to be drawn upon in today’s fnternational Space Station effort.

However, neither Time nor many of its readers were entirely fooled. The lack of transparency in the early Soviet missions meant that it was virtually impossible to determine what kind of spacecraft Komarov, Yegorov and Feoktistov had ridden into orbit. Rumours quickly abounded in the western press that longer multimanned flights were planned. Other rumours, which suggested that Voskhod 1 had been brought home early due to communications difficulties, the illness of a cosmonaut or a malfunctioning rocket, were firmly refuted by the Soviets. fn fact, the only light they publicly cast on the ‘new’ spacecraft was that it was lined with “a snowy-white, soft, sponge-like synthetic fabric’’, that its trio of cosmonaut seats were arranged in a row and that its instrumentation consisted of a navigation globe, telegraph key and a multitude of buttons and switches. ft was, admitted Time, ‘‘little help in deciding whether the Sunrise was entirely new or merely an improved version of the standard one-man Vostok-type spaceships”. Senator Clinton Anderson, chair of the Senate’s space and aeronautics committee, speculated that it weighed some 6,800 kg – not too much higher than its real 5,680 kg – and, further, hinted that this would make it possible to fly aboard a similar rocket to that used by Vostok.

Within days, on 28 October, plans for subsequent missions were laid out. The Vykhod flight, to be flown by Pavel Belyayev and Alexei Leonov, was tentatively pencilled-in for the first quarter of 1965, after which five others would undertake long-duration sorties of up to 15 days, conduct scientific research and perform another spacewalk. These would decisively surpass American plans to fly their first two-man Gemini in the spring of 1965, conduct a spacewalk that summer and attempt a 14-day endurance run thereafter. Hopes were high, wrote Nikolai Kamanin at the end of December, that five or six cosmonauts could be flown in a pair of spacecraft which would rendezvous and dock in orbit as early as 1966. After this, perhaps, a flyby of the Moon could be attempted.

Key to the success of the Vykhod mission – Voskhod 2 – was the 250 kg inflatable airlock through which Leonov would have to squeeze his way, all the time encased in a cumbersome, pressurised suit which would almost claim his life in orbit. On Gemini missions, an astronaut would venture outside by depressurising the capsule and opening the hatch. This was feasible because the American miniaturised electronic systems were capable of operating in vacuum. The fact that the Soviet

|

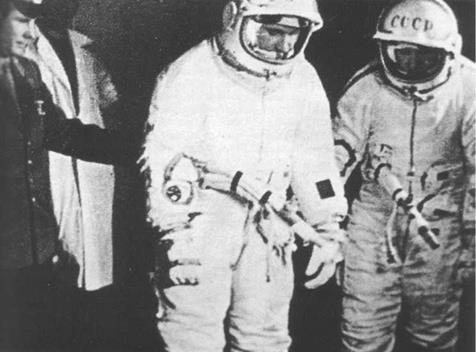

Belyayev and Leonov, both clad in EVA suits, prepare for their audacious mission. |

systems relied on air cooling meant that the capsule could not be depressurised and, hence, the airlock was born. Initial designs sketched out rigid structures, flexible contraptions and even one that could be rolled into a spiral before launch. The ‘winning’ design, codenamed ‘Volga’, envisaged a cylindrical device composed of 36 inflatable booms isolated in groups of 12. In this way, even if two groups of booms lost pressure, the airlock would retain its shape.

The airlock was not merely desirable, but necessary, since Voskhod’s avionics were cooled by cabin air and would overheat if the entire cabin was depressurised. Physically, it comprised a metallic ring, 1.2 m wide, which fitted over the spacecraft’s inward-opening hatch, and its length when fully deployed amounted to 2.5 m. Oxygen to inflate and pressurise the airlock booms was supplied by four spherical tanks and took around seven minutes to complete in orbit. The chamber boasted two lamps and three 16 mm cameras – two inside, one outside – and control of the inflation procedure would be performed from inside the cabin by Belyayev. However, a backup set of controls for Leonov’s use were suspended on bungee cords inside the Volga airlock itself.

For two years, the cosmonauts and their backups – Dmitri Zaikin and Yevgeni Khrunov – trained to a point at which the spacecraft’s cabin and airlock seemed like a second home, albeit a cramped one. In his autobiography, Leonov would recall his close friendship with Belyayev and express relief that attempts to remove ‘Pasha’

from Voskhod 2 on the basis of an old leg injury sustained in a parachute accident were not successful. “There were those,” Leonov wrote, “who had wanted Yevgeni Khrunov to command the mission… but I lobbied hard for Pasha, whom I thought more capable than Khrunov. I had worked with him more; I trusted him. In the end they agreed, though it caused some rancour with Khrunov.” Instead of commanding the prime crew, Khrunov would instead shadow Leonov on the backup team. Other attempts to fly another cosmonaut, 43-year-old Georgi Beregovoi, were quashed by Nikolai Kamanin; not on the basis of his age, but in view of his height and weight, both of which were greater than Belyayev, Leonov, Zaikin or Khrunov.

Much of Leonov’s preparation for the actual spacewalk, which would last between ten and 15 minutes, was undertaken in a modified Tupolev Tu-104 aircraft, flown in a series of parabolic arcs to simulate weightlessness for periods of up to 30 seconds at a time. It was time-consuming and imperfect, wrote Leonov, since “there was no way of simulating pure weightlessness in any laboratory on the ground. . . such limited, disconnected periods meant that the hour and 15 minutes of exiting the spacecraft, performing the spacewalk and re-entering the airlock had to be practiced over the course of over 200 Tu-104 steep climbs’’. Astronaut Deke Slayton, who would fly with Leonov on the Apollo-Soyuz mission ten years later, remembered the world’s first spacewalker recounting that he needed to build his upper-body muscles and indulged in diving “to test his equilibrium”. Leonov also, according to Asif Siddiqi, “cycled about a thousand kilometres in less than a year, carried out more than 150 EVA training sessions and jumped by parachute 117 times’’. Elsewhere, pressure-chamber tests with Zaikin and Khrunov satisfactorily evaluated the performance of the airlock at conditions equivalent to an altitude of 37 km. At around the same time, early in February 1965, the mission was redesignated as Voskhod 2, rather than Vykhod (‘Exit’), which it was felt would give away its true nature.

As their March 1965 launch date drew nearer, plans were afoot to despatch an unmanned precursor, Cosmos 57, to demonstrate the performance of the Volga airlock. Early on 22 February, three weeks before Belyayev and Leonov were due to fly, it was blasted into orbit… and, shortly thereafter, it exploded! Telemetry signals intercepted by American intelligence hinted that its airlock had successfully deployed and tests of opening and closing its outermost hatch were in progress. Then, the hatch was automatically closed and further telemetry indicated that commands to repressurise the airlock had been issued and accepted by Cosmos 57. Television images transmitted from the spacecraft revealed that the airlock appeared to have fully inflated. ‘‘During the first orbit,’’ wrote Nikolai Kamanin in his diary, ‘‘the craft was observed by special television circuit at Simferopol and Moscow [ground stations] … Quite unexpectedly, a distinct image of the front part of the airlock appeared on the screen, causing an outburst of joy among all present.’’

Unfortunately, the Klyuchi and Yelisovo ground stations, both in Kamchatka, then issued simultaneous commands to deflate the airlock, which confused Cosmos 57 and which it interpreted as an instruction to commence descent. The spacecraft automatically set the retrofire process in motion, but the TDU-1 rocket fired improperly. Spaceflight analyst Sven Grahn has mentioned on his website that

Cosmos 57 apparently began to tumble; this was at least partly due to the unjettisoned airlock, whose presence would have displaced the spacecraft’s centre of mass and induced the spinning. Twenty-nine minutes later, as programmed, the onboard destruct system – designed to prevent sensitive hardware from falling into enemy hands – was automatically activated to destroy Cosmos 57. A post-flight accident commission found that Klyuchi alone was permitted to transmit the airlock-deflation command and that Yelisovo should only have done so as a backup measure and only if directed by the Moscow control centre. In his diary, Kamanin would blame the poor security of commands being issued to orbiting spacecraft and felt that such weaknesses could be exploited by the United States.

Sergei Korolev faced a quandary. Only one other Voskhod capsule was ready to fly and the spacewalk could not be attempted until the airlock had been satisfactorily evaluated on a fully-successful mission. On 7 March, a Zenit reconnaissance satellite, under the cover name of ‘Cosmos 59’, was launched. A key concern was that, assuming the inflatable airlock jettisoned successfully after Leonov’s spacewalk, its attachment ring would rise 27-40 mm above the surface of the capsule; however, if it only partially separated, the ring could be as much as 80 mm high. In such an eventuality there was a chance that the asymmetry of the ring on the upper heat shield could impart a rotation on the Voskhod, perhaps affecting the safe deployment of the drogue parachute during descent. Cosmos 59 was equipped with an identical airlock attachment ring to that planned for Voskhod 2 and its eight-day mission was entirely successful, proving, with just days to spare, that Belyayev and Leonov could survive re-entry and landing with this in place.

Nonetheless, in his autobiography, Leonov would recount the Chief Designer’s concern that he and Belyayev should have the final decision over whether to fly their mission. Leonov also wrote of Korolev’s visible exhaustion: he had suffered from high fever as a result of lung inflammation and, indeed, would die early the following year, after prophetically declaring Voskhod 2 as the ‘‘last major work of his life’’. Korolev told the men that they had two options: they could wait a year for another Voskhod to be built, fly one spacecraft unmanned to complete Cosmos 57’s mission and then launch Belyayev and Leonov, or they could take a risk and fly the manned mission immediately. ‘‘Then, very cannily,’’ wrote Leonov, ‘‘he added that he believed the Americans were preparing their astronaut Ed White to make a spacewalk in May. He knew how to get our competitive juices flowing. He must have known what we would say. We didn’t want to lose a year.’’