Space Spectaculars

JOURNEY TO SPACE

The frigid cold of space held no fear for Alexei Arkhipovich Leonov. Growing up in central Siberia at the height of Stalin’s purges, he had seen far worse times. One of the most traumatic was in January 1938. He was just four months shy of his fourth birthday when neighbours in the tiny village of Listvyanka, near the point where the Angara River leaves Lake Baikal, arrived in the bitterness of midwinter to strip bare his family’s belongings, their clothes, their meagre furniture and even their food. The young boy, one of a dozen Leonov children, was even told to remove his trousers. It was the punishment meted out by the harsh Soviet regime on Arkhip Leonov, a staunch Bolshevik falsely accused of being an ‘enemy of the people’. He had, it was said, deliberately allowed seeds for the next year’s harvest to dry out.

‘‘My father was thrown into jail without trial,’’ Alexei Leonov wrote decades later in a joint autobiography, co-authored with American astronaut Dave Scott. ‘‘As we were then regarded as the family of an ‘enemy of the people’, we were branded subversives. Our neighbours were encouraged to come and take from us whatever they wanted.’’ His elder siblings were removed from school and the family was forced to leave Listvyanka. Ultimately, remembered Leonov, his father was absolved from blame, thanks to glowing testimony from a former commanding officer, received compensation and was offered the headship of his local collective farm. Arkhip Leonov declined, however, and chose to work instead at a power plant in Kemerovo, on the Tom River, to the north-east of Novosibirsk, with his sister and brother-in-law. It was here that the man who would one day become the first to walk in space first experienced his life’s two passions: art and aviation.

In his autobiography, he recounted drawing pictures on the whitewashed stoves of his neighbours’ rooms, earning extra bread and receiving pencils and paints for his efforts. ‘‘I loved to draw,’’ Leonov wrote, and his interest was indulged by his parents, who stretched bed sheets over wooden frames to provide rough canvasses for his work in oils. His ambition to become a professional painter was, he added, eclipsed one day in 1940 by the desire to fly. ‘‘It happened the first time I set eyes on

a Soviet pilot,” he explained, “who had come to stay with one of our neighbours. I remember how dashing he looked in his dark-blue uniform with a snow-white shirt, navy tie and crossed leather belts spanning his broad chest. I was so impressed. I used to follow him everywhere, admiring him from a distance.”

The pilot, after a time, noticed the young boy’s interest and demanded to know why he was being followed. When Leonov told him that he, too, desired to be a pilot, the aviator smiled and explained that he would need to grow physically strong and study hard at school. Equally importantly, Leonov would have to wash his face and hands each morning with soap. “Like most little boys,’’ wrote Leonov, “I was not too keen on soap and water,’’ but he followed the pilot’s advice, running to him every morning to proudly display his clean face and hands.

Acquittal from false accusation was by no means the end of the family’s troubles, as German forces rolled into the Soviet Union in a sweeping advance on a very broad front. Leonov recalled seeing truckloads of wounded Russian soldiers arriving in Kemerovo and the mass construction of chemical plants, two of which were blown up by Nazi sympathisers. In the autumn of 1943, when Leonov started school, the Red Army had repulsed the Germans at Stalingrad, although times remained grim. Years later, he would remember chanting thanks to Stalin in school for his ‘happy childhood’ and, indeed, would grow up believing the despotic Soviet system to be the best in the world. Not until his mid-teens would he begin reading and learning of other, happier worlds beyond the borders of Russia. When Nikita Khrushchev came to power, Leonov took the black armband he had worn in mourning of Stalin’s passing and burned it.

His ambition to become a professional artist culminated, in early 1953, with a journey in the back of an open lorry to Latvia to apply for a college place in Riga. This, sadly, came to nothing. Despite being accepted by the principal, Leonov’s realisation that the expense of living in the Latvian capital was simply too high pushed him in another direction, toward his second love: aviation. In the autumn, he was offered a place at the Kremenchug Pilots’ College in the Ukraine and for two years learned to fly propellor-driven aircraft, then moved on to the higher military academy in Chuguyev to train on MiG-15 jets. Shortly afterwards, the effects of the 1956 Hungarian Uprising placed Leonov and other young Soviet Air Force fighter pilots on full combat alert. Graduation from Chuguyev coincided broadly with the launch of Sputnik, at which time he was flying MiG-15s, specially modified to take off and land on soil airstrips at night and during the daytime.

One harrowing incident in particular brought him to the attention of a mysterious recruiting team. . . and paved the road to the cosmonaut corps. Whilst flying in heavy cloud, a pipe in his jet’s hydraulic system snapped. Alerted by his on-board instruments to a fire, Leonov shut off the fuel supply to the engine and performed an emergency landing. He was too low, he wrote, to parachute to safety. His actions drew the recruiters to ask ‘‘if I would be willing to join a school of test pilots’’. In October 1959, two years after Sputnik 1, he was one of 40 semi-finalists selected from a pool of thousands of highly-qualified MiG-15 and MiG-17 fighter pilots. Interestingly, the same questions had arisen in Russia as the United States over what kind of individuals were best suited to space travel: and pilots were considered

Journey to space 181

the best option, in light of their ability to work under extreme conditions, react with lightning speed and demonstrate a range of complex engineering skills.

For a month, he and the other candidates underwent gruelling physical and mental evaluations. “We were put in a silent chamber,” Leonov wrote, “and set a series of complex tasks while blinking lights, music and noise were played to distract us. We were given mathematical problems to solve while a voice was piped into the chamber giving us the wrong answers. We were put in a pressure chamber with very little oxygen in extreme temperatures to see how long we could withstand it.” By now, it was becoming clear to the 25-year-old pilot that this evaluation was for something more serious than test flying and suspicions abounded that missions into space were on the agenda.

At length, the candidates returned to their air bases – Leonov himself was shortly to be posted to East Germany, barely 20 km from the border with the West – to await further orders. Before leaving, he married his girlfriend, Svetlana. Within months, however, in March I960, he was recalled to Moscow to commence cosmonaut training. It was during this period that he first met Sergei Korolev, the man whom Leonov would credit with masterminding virtually the entire early Soviet space programme. “Our training was intensive,” he wrote, “a punishing regime which pushed us beyond what we thought we were physically capable of. Every day started with a 5 km run, followed by a swim, before we even began our individual programmes. Every aspect of our daily routine was carefully monitored by a team of doctors and nutritionists.” The trainees were also enrolled in the Zhukovsky Higher Military Academy for academic accreditation.

Five of Leonov’s colleagues rocketed into orbit between 1961 and 1963, together with a woman, and at around the time of Valentina Tereshkova’s flight, he received his first introduction to a new type of spacecraft: the ‘Voskhod’ (translated variously as ‘Dawn’, ‘Sunrise’ or ‘Ascent’). During a visit to Korolev’s OKB-1 bureau, he was captivated by the ‘‘more interesting design’’ of one capsule in particular. It had, he wrote, ‘‘a transparent airlock attached, with a movie camera installed’’. Korolev explained that all sailors on ocean liners were required to swim and, by extension, all cosmonauts should learn how to ‘swim’ in open space. The airlock, which extended like a large blister from the Voskhod, would be used for just such an exercise. Leonov was told to don a training space suit and evaluate the airlock. At that moment, he recalled years later, Yuri Gagarin, the first man in space, clapped him on the back and whispered that Korolev had just chosen Leonov for the assignment.

That assignment, which would reach fruition with a launch from Tyuratam on 18 March 1965, would make him not only the first man to walk in space, but also half of the world’s first-ever two-man cosmonaut crew. The Voskhod vehicle that Leonov and fellow pilot Pavel Ivanovich Belyayev were to fly would look physically similar to Vostok and had actually been adapted to carry crews of two or three men for, conceivably, up to two weeks at a time. It was, admittedly, another of Nikita Khrushchev’s cynical and short-sighted ploys to outdo American plans to launch their two-man Gemini capsules, three-man Apollo missions and conduct spacewalks. Although only two manned Voskhods ever flew – the first with a crew of three, including a scientist and physician, the second with Leonov and Belyayev – they

|

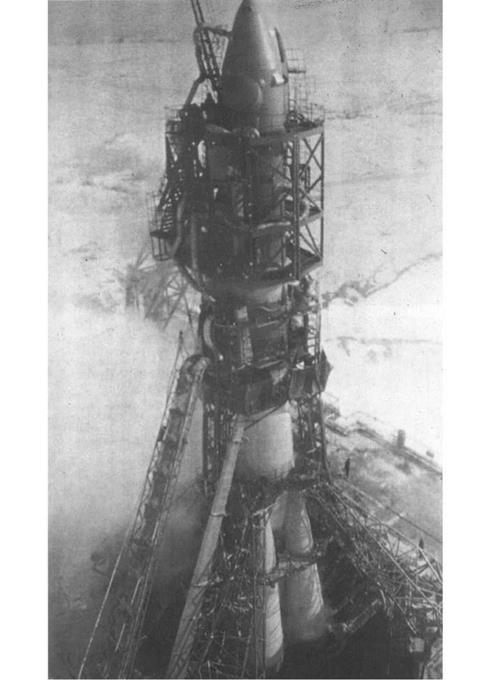

Voskhod 2 is readied for launch. Note the ‘blister’ in the side of the nose shroud, caused by the projecting airlock. |

would prove themselves to be among the most dangerous and reckless space missions ever attempted.