THE JOKER

Right from the start, Walter Marty Schirra Jr was known for his ‘gotchas’.

Born in Hackensack, New Jersey, on 12 March 1923, he was once described as having aviation in his blood; his parents having both engaged in ‘barnstorming’ and ‘wing-walking’ during the Twenties. As his father Walter, a veteran First World War fighter pilot and engineer, handled the controls of a Curtiss Jenny biplane, his mother Florence danced on the lowermost wing, using the struts for support. Spectators in Oradell, New Jersey, paid up to five dollars a time to witness the Schirras’ stunts. Fortunately, wrote the astronaut, his mother ‘‘gave up wingwalking when I was in the hangar!’’ Nevertheless, he would use his mother’s experience to his advantage: unlike the celebrated, faster-than-sound test pilots Chuck Yeager and Scott Crossfield, Schirra was flying even before he was born…

He graduated from Dwight Morrow High School in Englewood, New Jersey, in 1940 and attended the Newark College of Engineering, before being appointed to the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. His disappointed father had wanted him to attend West Point as an Army officer, but in his autobiography Schirra would recall seeing a naval aviator during his boyhood, clad in ‘‘green uniform, the sharp gold wings above his left pocket and his polished brown shoes shiny. From that day on, I always wanted to go to Navy’’. Schirra underwent an abbreviated class, ‘‘a five – year programme… crammed into three’’, received his degree in 1945 and served two years at sea in the Pacific. Not only was his education abbreviated, but so too was his whirlwind romance with Jo Fraser, whom he met, courted for seven days and finally married whilst on leave in February 1946.

A tour of duty in China, attached to the staff of the commander of the Seventh Fleet as a briefing officer, meant that Schirra was a witness to the communist revolution sweeping across the most populous nation on Earth. ‘‘A high crime rate in the neighbourhood in which Jo and I lived,’’ he wrote, ‘‘practically a robbery a night, was an expression of revolutionary contempt for the American ‘imperialists’ . . . I knew when we left that China would never be the same again.’’ Shortly thereafter,

|

|

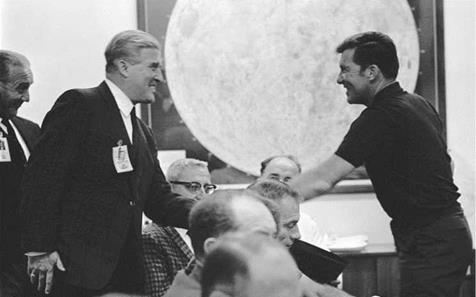

Wally Schirra (right) and Wernher von Braun.

and proving that aviation was truly in his blood, Schirra became the first member of his academy to be detailed for flight training, transferring to Pensacola Naval Air Station in Florida and receiving his wings in June 1948. Like Scott Carpenter, he started off by soloing in a Yellow Peril biplane and then flew naval fighters for three years. Upon the outbreak of war in Korea, Schirra volunteered for active service as an exchange aviator with an Arkansas-based Air National Guard unit. He spent eight months in south-east Asia, flew 90 combat missions in the F-84 Thunderjet fighter-bomber and shot down two MiG-15s – “a tough little adversary” – for which he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Following Korea, Schirra served at the Naval Weapons Center in China Lake, California, during which time he participated in the initial development of the Sidewinder air-to-air missile and later served as chief test pilot for the F-7U Cutlass and FJ-3 Furyjet fighters at Miramar Naval Air Station in San Diego. Although he praised the usefulness of the Cutlass in better understanding the aerodynamics of a delta-winged aircraft, Schirra would reject it on the basis that if it stalled with its leading-edge slats ‘in’, its motions became wild and random, with ejection the pilot’s sole option. The Cutlass would later be declared operational, much to the chagrin of Schirra and the other members of his flight-test group, who had seen a number of fatalities. Indeed, over a quarter of all Cutlasses built would be lost in accidents. Years later, he would refer to it darkly as a ‘‘widow-maker’’.

Schirra completed the Naval Air Safety School and a tour of the Far East aboard the Lexington, before being selected for and reporting to the Naval Test Pilot School at Patuxent River, Maryland, in January 1958. ft was at this time, he wrote, that he learned to communicate effectively with engineers, ‘‘the most valuable asset that f took from test pilot school to the space programme”. For each test, Schirra was required to report in depth on tactical manoeuvres, power settings and data points. Within the next two years, he would be applying this expertise to the development of Project Mercury. Whilst at Pax River, Schirra met three other hotshot naval aviators, Pete Conrad, Dick Gordon and Jim Lovell, who would themselves later become astronauts. Graduating in late 1958, he assumed duties as a fully-fledged test pilot, transferring to the famed Edwards Air Force Base in California to help evaluate the F-4H Phantom-II long-range supersonic fighter-bomber.

Then, like more than a hundred other Navy, Air Force and Marine fliers across the United States, in the spring of 1959 Schirra received classified orders to attend a briefing in Washington, DC. Initially, he was reluctant to undergo the months of training for the much-lambasted ‘man-in-a-can’ effort to send an American into space. ‘‘I wanted to be cycled back to the fleet with the F-4H, get credit or take blame for its performance and put it through its paces as a tactical fighter,’’ he wrote. ‘‘I saw myself as the first commander of an F-4H squadron. The space programme to me was a career interruption.’’ Despite his reluctance, Schirra underwent the gruelling tests at Lovelace and Wright-Patterson, realising that as other hotshot pilots fell by the wayside, he was on the cusp of joining the most elite flying fraternity of all.

Undoubtedly, Schirra’s experience had placed him in mortal danger on many occasions, yet his lifetime motto remained: ‘‘Levity is the lubricant of a crisis’’. In fact, on the day the Mercury Seven were introduced to journalists in April 1959, Deke Slayton remembered Schirra telling a joke. It was not his first, nor would it be his last, and he would be in good company in the dark-humour stakes. All seven of them would dream up their own fiendish practical jokes – called ‘gotchas’ – which they inflicted on each other, on flight surgeons, on their nurse, Dee O’Hara, on Henri Landwirth and on an unfortunate Life photographer named Ralph Morse. The latter, who had succeeded in his own ‘gotcha’ by tracking them down on a desert-survival training exercise in Reno, Nevada, received his comeuppance at the hands of Schirra and Al Shepard. The pair planted a smoke flare in the exhaust pipe of Morse’s jeep and told him to move the vehicle, whereupon the unsuspecting photographer hit the starter and – boom! – was engulfed in a cloud of green smoke and dust. ‘‘The jeep had to be towed back to Reno,’’ Schirra recounted with glee, ‘‘and sold for scrap.’’

On other occasions, the Mercury Seven would coat the bottoms of each other’s metal ashtrays with thin films of gasoline, causing a flash fire whenever one of them inadvertently flicked hot ash. ‘‘Fiendish, but fun,’’ Schirra wrote. Henri Landwirth, who frequently played host to the astronauts at his Holiday Inn, once found a live alligator in his pool, cunningly secreted there by Al Shepard. Flight surgeon Stan White, who had purchased a new sports car, liked to brag about its high efficiency. ‘‘So we plotted his comeuppance,’’ wrote Schirra. ‘‘For a week, we added gasoline to his tank, a pint a day, and he raved about the great mileage he was getting. The following week, we siphoned off a pint a day and he went berserk. White never did figure it out.’’

Schirra’s humour would form an essential part of astronaut morale over the

coming years, under the respective shadows of both triumph and tragedy. Only weeks before his first spaceflight aboard Sigma 7, Dee O’Hara became his latest victim. . .