EUPHORIA, DISAPPOINTMENT… AND A BOSS

The weeks after Friendship 7 would be filled with euphoria over lohn Glenn’s achievement, tempered with disappointment over the fate of Deke Slayton, the man meant to follow him into orbit on the next Mercury-Atlas mission.

Relief at Glenn’s safe return was evident on many faces, including that of lawyer Leo D’Orsey, who had personally endorsed a $100,000 cheque for Annie to cover her husband’s life insurance in the event of a disaster. (Despite D’Orsey’s attempts to purchase million-dollar policies, the astronauts were uninsurable.) Now, thankfully, it did not need to be cashed. “Boy, am I glad to see you!’’ D’Orsey told Glenn later. Elsewhere, Henri Landworth, former manager of Cocoa Beach’s Starlight Motel and later of the Holiday Inn frequented by the astronauts, had made a 400 kg cake, shaped like Friendship 7. He even rigged up an air-conditioned truck to prevent it from spoiling. After Glenn sampled a slice, Landwirth told him that it had been made in time for the original lanuary launch date and was a month old!

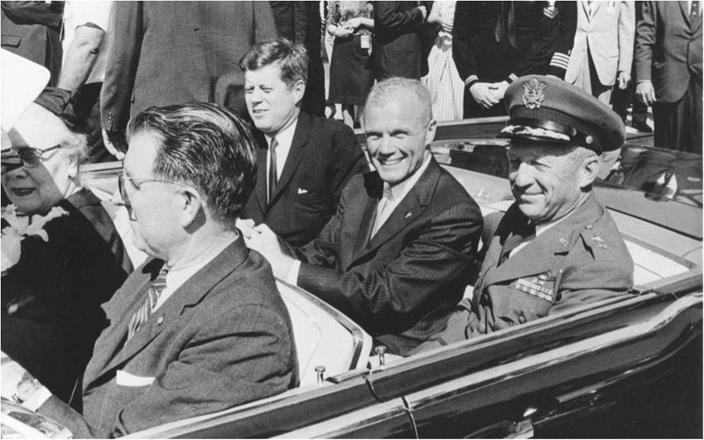

At Cape Canaveral, President Kennedy awarded the astronaut and Bob Gilruth with NASA’s Distinguished Service Medal, then flew America’s newest hero to Washington, DC, aboard Air Force One to address Congress and, later, enjoy a tickertape parade through the streets of New York. Whilst airborne, Kennedy introduced his four-year-old daughter Caroline to Glenn. Clearly accustomed to the flights of Ham and Enos, the little girl’s disappointed reaction was: “But where’s the monkey?’’

Like Shepard, Glenn was impressed by the president’s enthusiasm and passion for the space programme. “He believed… that it was not just a scientific journey,’’ the

|

|

astronaut wrote in his memoir, “but a source of inspiration that could motivate Americans to pursue great achievements in all fields.” Glenn had been accorded the rare privilege of addressing a joint session of Congress, which he did on 26 February, before the tickertape parade through New York. Four million people reportedly lined the streets to greet him and his speech before Congress led some columnists, including Arthur Knock and James Reston of the New York Times, to remark on his suitability for politics and his embodiment of “the noblest human qualities”. One group of Republicans from Nevada even called upon him to run for the presidency. Glenn would admit at the time that his interests were apolitical, but a cultivated friendship with, among others, Attorney-General Bobby Kennedy would gradually direct him towards a career in the Senate.

His diplomatic abilities were also put to the test in May 1962, when he was invited, along with Vostok 2 cosmonaut Gherman Titov, to address the Committee on Space Research, part of the third International Space Symposium, in Washington, DC. Glenn described Titov as “cordial but forceful and thoroughly indoctrinated. . . charts and photographs had supplemented my presentation, but not his; he followed the Soviet line that disarmament would have to precede full sharing of information”. Nonetheless, he hosted the cosmonaut during his visit to Washington, even debating the existence of God in front of journalists.

Titov’s standpoint was that he did not see anyone in space – offering clear “proof for the communist position’’ that such a deity did not exist – but Glenn responded that ‘his’ God was not so small that he expected to “run into Him a little bit above the atmosphere”. Diplomacy was extended still further when the Glenns invited the Titovs to a barbecue at their house; after initially refusing, the cosmonaut’s delegation changed its mind at the last moment. The Glenns, unprepared, were forced to ask their neighbours for spare steaks and send their police escorts to buy vegetables. Meanwhile, Al Shepard picked up the Titov delegation and bought the Glenns some time by taking a few wrong turns on his way to Arlington. . .

Not only was Glenn deemed valuable to the nation, but so too was Friendship 7, which, despite some discolouration, was in remarkable condition and today resides in the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC. In 1962, however, it undertook what was popularly nicknamed its ‘fourth orbit’: a global tour of 17 countries before eventually being installed in the Smithsonian, close to the Wright Brothers’ original aircraft and Charles Lindbergh’s ‘Spirit of St Louis’.

As Glenn basked in his new-found fame, 38-year-old Donald Kent ‘Deke’ Slayton fought a losing battle to fly his own Mercury-Atlas mission, tentatively scheduled for April 1962. He had already picked a name for his capsule – ‘Delta 7’, the fourth letter in the Greek alphabet for the fourth manned Mercury mission – which he would describe in his autobiography as ‘‘a nice engineering term that described the change in velocity’’. Slayton’s own velocity, both in spacecraft and high-performance aircraft, would decline markedly, thanks to a minor, yet persistent, heart condition, known as ‘idiopathic atrial fibrillation’. This took the form of occasional irregularities of a muscle at the top of the heart, caused by unknown factors and extremely rare in highly-fit thirtysomethings like Slayton. It had first arisen during a centrifuge run at Johnsville in August 1959, when physicians noticed traces of sinus arrhythmia, which Bill Douglas later wrote “wasn’t uncommon in healthy young men and… the kind of thing that often went away with exertion’’. After the run, however, it was still present, prompting Douglas and his team to undertake a clinical electrocardiogram at the Philadelphia Navy Hospital.

They concluded that Slayton had a ‘flutter’ in his heartbeat, although, in 1959, the astronaut himself ‘‘had no idea how much of a problem it was’’. Further tests at the Air Force’s School of Aviation Medicine in San Antonio, Texas, verified that the condition was of no consequence and should not influence Slayton’s eligibility for a spaceflight. Douglas informed Bob Gilruth, who briefed NASA Headquarters on the issue late in 1959, as well as the Air Force Surgeon-General, who advised that no further action was necessary. The ‘Slayton File’, for a time, lay dormant.

The problem resurfaced a little over two years later, a week before Friendship 7’s launch, when speculation arose that John Glenn had a heart murmur. Apparently, wrote Slayton, the call to Bill Douglas came from Air Force physician George Knauf, attached to NASA Headquarters, and had originated from ‘‘a source higher than the Department of Defense’’. Douglas denied that Glenn had a problem, but effectively opened a can of worms. Knauf asked next if Glenn’s backup, Scott Carpenter, had a heart murmur: again, the response was negative. Then Douglas, to reinforce the point that the matter was of little consequence, revealed that Slayton had long been known to have a minor condition. He expected this to be the end of the matter. It wasn’t.

Back in 1959, flight surgeon Larry Lamb had examined Slayton at Brooks Air Force Base in San Antonio and had become convinced the heart fibrillation should disqualify him from the selection process. ‘‘He hadn’t said so in 1959,’’ wrote Slayton, ‘‘but he said so now. I don’t think it was anything personal – this was just his medical opinion.’’ Lamb’s judgement was very much a voice in the wilderness, but unfortunately he also happened to be Lyndon Johnson’s cardiologist, and in the spring of 1962 began to question the astronaut’s suitability for flight. Three weeks after Friendship 7, Jim Webb reopened Slayton’s medical files and the astronaut and Douglas were summoned to the office of the surgeon-general of the Air Force in Washington, DC. A panel of military physicians signed him off as fit to fly, a decision endorsed by the Air Force’s chief of staff, General Curtis LeMay.

For Webb, though, it was not enough. The Secretary of the Air Force, Eugene Zuckert, suggested that a civilian panel of physicians should also examine Slayton at NASA Headquarters. On 15 March, less than two months before launch, Slayton was poked and prodded and had his heart monitored by Proctor Harvey of Georgetown University, Thomas Mattingley of the Washington Hospital Center and Eugene Braunwell of the National Institutes of Health. In a turnaround which, in Slayton’s own words, would leave him ‘‘devastated’’, Deputy Administrator Hugh Dryden entered the room and told him, point-blank, that he was off the flight. None of the physicians had found a specific medical reason to keep him off Delta 7, but their consensus was that if NASA had pilots ‘without’ his condition, one of them should fly the mission instead.

Years later, Slayton would refute theories that Lyndon Johnson’s annoyance over the Annie Glenn incident had anything to do with the decision, but certainly felt it was a political move. “NASA knew it would have to publicly disclose my heart condition prior to my flight,” he wrote. “There would be medical monitors at tracking stations all over the world who wouldn’t know how to react otherwise. Everybody expected this to be a big deal. NASA would be opening itself up to a lot of medical second-guessing.” Bill Douglas felt that problems could arise if Slayton started fibrillating on the pad – “do you scrub the launch or go ahead?’’ – but he, Bob Gilruth and Walt Williams had confidence that he was the best person to follow John Glenn. All three men were prepared, personally, to take the heat, but Jim Webb’s fear that it could trigger adverse headlines for the agency drew a line in the sand. “It didn’t matter that a whole lot of doctors thought I didn’t have a problem,’’ Slayton wrote of Webb’s actions. “He was only going to listen to the few who did.’’

In Webb’s mind, an Atlas abort could subject the astronaut to acceleration loads as high as 21 G and conjured the very real possibility that Slayton, dehydrated and perhaps fibrillating, could die as a result. The impact on NASA, on President Kennedy’s promise to land a man on the Moon before the end of the decade and on the ongoing contest with the Soviets could be profound.

The next day, 16 March, the now-grounded, and furious, astronaut was forced to sit through a lengthy press conference, in which the minutiae of the case were examined. Hugh Dryden remarked that, despite the decision, Slayton might remain eligible for future flights. One journalist asked if the problem had been caused by stress, to which Slayton responded no, and further that he did not even know about it until he had been hooked up to an electrocardiogram in 1959. The most stressful part of the space business, he explained caustically and with more than a hint of sarcasm, was “the press conference after the flight’’. Bill Douglas’ own departure from NASA within days of the announcement, to return to the Air Force, was leapt upon by some journalists as ‘evidence’ of his bitterness over Slayton’s treatment. In truth, Douglas was already at the end of a three-year detachment to NASA and his transfer had been in the works since mid-1961.

Despite his grounding, Slayton did not give up on flying. ‘‘I made some changes in my lifestyle,’’ he wrote, ‘‘gave up drinking, started working out more regularly – quit doing everything that was fun, I guess!’’ Thanks to Bill Douglas, he also secured an examination by Dwight Eisenhower’s cardiologist, Paul Dudley White, in June 1962. White advised him that two-thirds of people with his condition would die young, whilst the remainder would probably never know they had it and might never be affected. The verdict: ‘‘Young man, you’re going to live a long time.’’ (Slayton lived to be 69.) However, White’s report, which highlighted that Slayton did not appear to have a problem, also advised that if astronauts were present without the condition, it would be preferable to assign them in his stead. As it became clear that he would not draw any of the remaining Mercury-Atlas flights, Slayton turned his gaze to the two – man Gemini project, only to be told by Bob Gilruth that his condition would make him a ‘‘hard sell’’ to senior management. Shortly thereafter, the Air Force decreed that he no longer met the qualifications for a Class I pilot’s licence – effectively, he could no longer fly solo – and, at the end of November 1963, Slayton tendered his resignation from the service.

Although he would eventually get his ride into space, it would not come until July 1975, when he was 51 years old. A lesser man might have thrown in the towel and departed NASA for pastures new, but not Slayton. With no guarantee that he would ever fly, he decided to stay and in the summer of 1962, as the agency prepared to expand its astronaut corps by picking nine new pilots, he was appointed as Coordinator of Astronaut Activities. Initial plans to bring in a manager from the outside to oversee the corps were quashed by the astronauts themselves. “What we wanted the least,” wrote Wally Schirra, “was somebody who would outrank us and issue orders in a military way. We wanted someone who knew us, who trained with us. Deke was the one and only choice.” During the next few years, as America pushed for the Moon, Slayton, though non-flying, would be all-powerful within the astronaut corps, deciding the career paths of the men who would someday walk on the lunar surface. . . and those who would not.