“THE FIRST THING I HAD EVER LOST”

As Grissom moved smartly through his post-landing checks, a quartet of Sikovsky UH-34D helicopters, despatched from the recovery ship Randolph, were already on the scene. One of their crews, Jim Lewis and John Rinehard, had been tasked with raising Liberty Bell 7 from the water, after which the astronaut would explosively blow the hatch, exit the capsule and be winched aboard the chopper. Seconds after splashdown, Grissom radioed Lewis, callsigned ‘Hunt Club 1’, to ask for a few minutes to finish marking switch positions. Finally, after confirming that he was ready to be picked up, he lay back in his couch and waited. All at once, he recounted, ‘‘I heard the hatch blow – the noise was a dull thud – and looked up to see blue sky… and water start to spill over the doorsill’’. The ocean was calm, but Mercury capsules were not designed for their seaworthiness, particularly with an open hatch, and Liberty Bell 7 started to wobble and flood. Grissom, who later admitted that he had ‘‘never moved faster’’ in his life, dropped his helmet, grabbed the right side of the instrument panel, jumped into the water and swam furiously. ‘‘The next thing I knew,’’ he said, ‘‘I was floating high in my suit with the water up to my armpits.’’

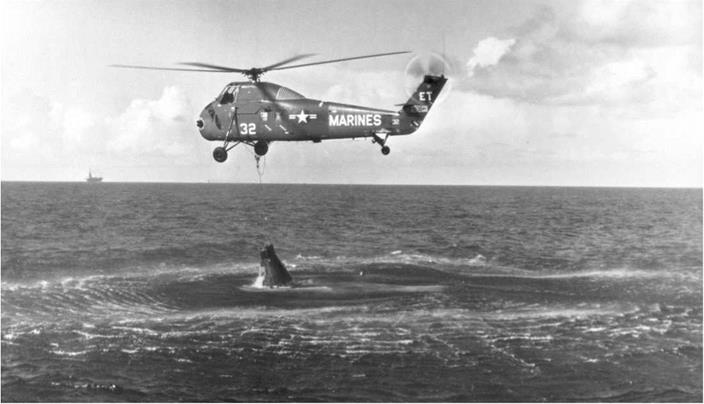

Although both cap and safety pin were off the detonator, Grissom would later explain that he did not believe he had hit the button to manually blow the hatch. ‘‘The capsule was rocking around a little, but there weren’t any loose items… so I don’t know how I could have hit it, but possibly I did,’’ he told a debriefing that morning aboard the Randolph. Lewis, meanwhile, had to dip his helicopter’s three wheels into the water to allow Rinehard to hook a cable onto the now-sinking Liberty Bell 7. ‘‘Fortunately,’’ Lewis recounted, ‘‘the first time John tried, he managed to hook-up while the capsule was totally submerged.’’ Grissom, by now in the water, was puzzled, anxious and then angry when the helicopter did not lower a horse collar to hoist him aboard. Lewis, whose own training had shown him that Mercury pressure suits ‘‘floated very well’’ and had seen the astronauts apparently enjoying their time in the water, had no idea that Grissom was actually close to drowning. The astronaut had inadvertently left open an oxygen inlet connection, which allowed water to seep into his suit and air to leak out, thus reducing his buoyancy. Although he closed the inlet, some air also seeped from the neck dam, causing him to sink lower and regret the weight of souvenirs in his pockets.

Grissom did not know that Lewis was himself struggling with the spacecraft: in addition to the waterlogged capsule, the landing bag had filled with seawater and it now weighed in excess of 2,000 kg – some 500 kg more than the helicopter was designed to lift. Although Lewis felt he could generate sufficient lift to raise Liberty Bell 7 and take it back to the Randolph, every time he pulled it clear of the water and it drained, a swell would rise and fill the capsule again. Lewis’ instruments told him that the strain on the engine would allow him only five minutes in the air before it cut out. He therefore released the $2 million capsule to sink in 5,400 m of water and requested that another chopper fish Grissom from the water while he nursed his own aircraft back to the ship.

Unaware of the difficulties the astronaut was having – they assumed that his frantic waving was to assure them that he was fine – it was several more minutes before the second helicopter, with the familiar face of George Cox aboard, dropped him a horse collar, which he looped around his neck and arms (albeit backwards) and was lifted to safety. Grissom was so exhausted that he could not even remember the helicopter had dragged him across the water before he finally started ascending. He had been in the water for only four or five minutes, ‘‘although it seemed like an eternity to me,’’ he said later. His first request upon arrival on the Randolph’s deck

|

|

was for something to blow his nose, as his head was full of seawater. A congratulatory call from President Kennedy fell on deaf ears as, for the first time, “my aircraft and I had not come back together. In my entire career as a pilot, Liberty Bell 7 was the first thing I had ever lost”. Worse was to come. At his first postmission press conference, and in the years to follow, Grissom would be grilled by journalists, not over the success of his mission, but over the festering question of whether he had contributed to the loss of his spacecraft by blowing the hatch. It was an accusation that Grissom would refute until the day he died.

Not surprisingly, his temperature and heart rate were both high when he arrived aboard the Randolph. Physicians described him as “tired and… breathing rapidly; his skin was warm and moist”. Years later, although it was known that Grissom had an abnormally high heart rate, Tom Wolfe, in his bestselling book ‘The Right Stuff5, would point to his physiological state as ‘evidence’ that he had panicked inside Liberty Bell 7 and possibly blown the hatch. Even Grissom, at his first postflight press conference in Cocoa Beach’s Starlight Motel, admitted that he was ‘‘scared’’ during liftoff, an admission later jumped upon by the media as proof that America’s second spaceman had displayed a chink of weakness. Test pilots at Edwards Air Force Base in California scornfully mocked that Grissom had ‘‘screwed the pooch’’ – had made a terrible mistake – and even the astronaut’s two sons were lambasted by their schoolmates for the loss of the capsule. In his own summing-up for Life magazine, Grissom admitted that ‘‘if a guy isn’t a little frightened by a trip into space, he’s abnormal’’. Chris Kraft agreed, pointing out that ‘‘if you weren’t nervous, you didn’t know what the hell the story was all about’’.

A subsequent investigation from August to October 1961, which included Wally Schirra on its panel, would determine that the astronaut did not contribute in any way to the mysterious detonation of the hatch. Indeed, said Schirra, whose design of the neck dam had helped save Grissom’s life, ‘‘there was only a very remote possibility that the plunger could have been actuated inadvertently by the pilot’’. During the inquiry, Schirra, fully-suited, even wriggled into a Mercury simulator himself and, no matter how hard he tried, could not ‘accidentally’ trigger the hatch’s detonator. One of the conclusions reached by the Space Task Group was that a 76 cm-diameter balloon would be installed in future capsules to allow recovery ships to pick up the spacecraft if the helicopters were forced to drop them.

Many other engineers and managers shared the astronauts’ conviction that Grissom was blameless. However, even though confidence in him remained high and he went on to command the first two-man Gemini mission, the stigma refused to go away. Some engineers continued to mutter of ‘‘a transient malfunction’’, but had no ability to identify it because the evidence lay on the floor of the Atlantic. Not until 1999 would Liberty Bell 7 be salvaged and raised to the surface.

Grissom himself participated exhaustively in the investigation. ‘‘I even crawled into capsules and tried to duplicate all of my movements,’’ he said, ‘‘to see if I could make the whole thing happen again. It was impossible. The plunger that detonates the bolts is so far out of the way that I would have had to reach for it on purpose to hit it. . . and this I did not do. Even when I thrashed about with my elbows, I could not bump against it accidentally.” Moreover, to hit the plunger manually would have required sufficient force to produce a nasty bruise, which Grissom did not have. Possibilities explored over the years have included the omission of the ring seal on the detonator’s plunger, static electricity from the helicopter, a change of temperature of the exterior lanyard after splashdown or – a hypothesis that Grissom supported – the entanglement of the lanyard with the straps of the landing bag. Walt Williams, writing in Deke Slayton’s autobiography, considered the astronaut to be blameless, but thought it “very possible’’ that he had bumped the plunger accidentally with his helmet.

Launch pad leader Guenter Wendt, speaking in 2000, fiercely discounted all theories but one: the entanglement of the exterior lanyard. “It is the most logical explanation,” he said, but acquiesced “Can we prove it? No.’’ It is a pity that the mishap – however it happened – should have, in the eyes of the public, marred what had otherwise been a hugely successful mission and which cleared the way for John Glenn’s historic orbital flight in February 1962. Was the unfortunate, twice-cracked Liberty Bell to blame for its spacegoing namesake’s watery demise? All Grissom would say was that Liberty Bell 7 “was the last capsule we would ever launch with a crack in it!’’