“LET’S GO!”

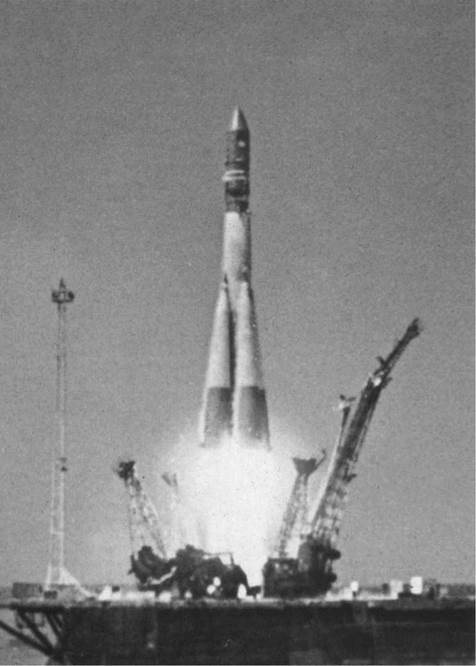

His voice exhibited clarity, calmness and confidence when Korolev called over the radio an hour before launch for a status update. To alleviate the boredom, Pavel Popovich, the cosmonaut on duty in the control bunker, arranged for some music to be played. This stopped abruptly at 8:51 am as Korolev gruffly announced that, with a little over 15 minutes to go, it was time for Gagarin to seal his gloves and close his visor. Unlike their counterparts in the United States, no ‘5-4-3-2-1’ countdown was followed; the R-7 was simply fired at the appointed time. As a result, the last few seconds before humanity’s first voyage into space were almost anti-climatic. With steady rhythm, Korolev barked out in turn: ‘‘Launch key to ‘go’ position. . . Air purging… Idle run,’’ and, finally, at 9:07 am, ‘‘Ignition!’’ The gantry’s supporting arms sprang clear from the sides of the rocket as its 20 kerosene-fed engines, with an explosive yield of 880,000 kg, roared to full power.

Gagarin would later describe the initial sensation of liftoff as ‘‘an ever-growing din’’, albeit no louder than the sounds he had experienced flying high-performance jets at Nikel. His helmet muffled much of the R-7’s rumble, although the vibrations remained apparent. At some point, a few seconds after leaving Earth, he yelled the immortal words ‘‘Poyekhali!’’ (‘‘Let’s go!’’) over the radio circuit. Within two minutes, as the G loads began to build, he found it increasingly difficult to speak and would later compare the sensation to the stress of a harsh turn in a MiG. The pressure lifted momentarily as the R-7’s four strap-on boosters burned out and separated; after a brief pause, the central core of the rocket accelerated and the G loads began to rise again. By three minutes into the flight, at 9:10 am, the Little Seven’s nose fairing was jettisoned from around Vostok’s ball, giving Gagarin his first glimpse of the dark blue sky and the clear curvature of Earth as he reached the edge of space.

The R-7’s core, now exhausted of propellant, finally fell away some five minutes into the flight, leaving Gagarin reliant on an upper-stage engine, which inserted him

|

into orbit promptly at 9:18 am, exactly as Korolev had planned. Unknown to the cosmonaut, the core had actually burned for longer than anticipated, leaving Vostok in an orbit with an apogee – high point – of 327 km, rather than the intended 230 km. It added a little more height to Russia’s already-won World Aviation Altitude Record. As Muscovites arrived at work and the western world still slumbered – figuratively and literally – a new era had begun. Gagarin, whose heart rate soared from 66 to 158 beats per minute during ascent, had won the first lap of the space race.

Although the noise and intense vibration of the R-7 was now gone, it was succeeded by the steady murmur of fans, ventilators, pumps and the hiss of static in his ears. His first experience of the state of weightlessness, properly termed ‘microgravity’, was hampered by the fact that he was tightly strapped into his ejection seat. However, he had purposely carried a small Russian doll as a gravity indicator and watched as it floated comically in midair. So too did a notepad and pencil. In fact, this would not be the doll’s only experience of space travel: in 1991, cosmonaut Musa Manarov would carry it on his mission to commemorate the 30th anniversary of Gagarin’s flight.

As the capsule slowly rotated, to avoid wasting propellant on unnecessary manoeuvres and also to ensure that various sections of Vostok did not become too hot or cold, the First Cosmonaut had his first opportunity to view the world through the Vzor. In his official statement, made in Moscow a few days later, he would describe ‘‘a smooth transition from pale blue, blue, dark blue, violet and absolutely black… a magnificent picture’’. He started jotting down observations in his notepad, but after the pencil floated away he turned instead to the on-board tape recorder to log his thoughts, describing weightlessness as ‘‘not at all unpleasant’’ and confirming that the food and drink were good. Two Russian schoolgirls, who would sample that same food in less than two hours’ time, would be inclined to disagree.

Ten minutes after launch, Vostok was heading eastwards in the direction of Siberia and Gagarin gradually drifted out of radio range with Tyuratam, to be picked up in turn by other listening posts at Novosibirsk, Kolpashevo, Khabarovsk and the easternmost station on Soviet soil, Yelizovo, near Petropavlovsk on the Kamchatka Peninsula. To attract Gagarin’s attention, each station transmitted musical themes to him: Muscovite tunes, ‘Waves of the Amur’, Baglanova songs and others. ‘‘During that early period,’’ Alexei Leonov wrote, ‘‘the Mission Control Centre at Yevpatoriya in the Crimea . . . was still under construction, so communication and control from the ground. . . were performed from the radio stations above which the spacecraft flew.’’ Leonov had been sent to the remote Yelizovo site a few days earlier as its cosmonaut representative and, to underline the secrecy, had no idea if Gagarin or Titov was aboard Vostok. Then, as the spacecraft passed over Kamchatka at around 9:21 am, he saw the first crude television images from the cabin. ‘‘I could not make out his facial features,’’ he wrote, ‘‘but I could tell from the way he moved that it was Yuri.’’

Leonov had been instructed not to initiate communications with Vostok unless given permission to do so and he duly remained silent. However, within moments, Gagarin radioed a request for details of his ‘‘flight path’’, keeping the orbital nature of the mission – for now – a secret from western ears. “The radio operator by my side did not realise his finger was depressing the button that opened the radio link… when he turned to speak to me,” Leonov wrote. The open mike broadcast the words of both Leonov and the radio operator straight up to Vostok. As soon as he heard Leonov tell the operator that “everything is going fine”, Gagarin responded with “Give my regards to Blondin”, fair-haired Leonov’s nickname.

The journey continued, cutting diagonally across the Pacific Ocean from volcanic Kamchatka’s land of fire and ice into darkness and toward the sleeping Americas. “The transition into Earth’s shadow,’’ Gagarin would explain to a Moscow press conference a few days later, “took place very rapidly. Darkness comes instantly and nothing can be seen. The exit from the Earth’s shadow is also rapid and sharp.’’ The unexpected suddenness of the shift from orbital daytime to nighttime led to some mutterings that the flight was a fraud; a testament, clearly, to how limited humanity’s understanding of space travel was at the time. Midway through the darkness, at 9:26 am, Vostok rose above the horizon of the Electronic Intelligence (ELINT) station on the Alaskan island of Shemya, giving the United States its first awareness that a Soviet man was indeed in orbit. Admittedly, American long-range radars had detected the R-7’s launch, but it was Shemya which confirmed without doubt that live dialogue was ongoing with an Earth-circling cosmonaut.

By 9:32 am, a stable orbit had been achieved – reaching a maximum apogee of 327 km and dipping to a perigee of 169 km, inclined 64.95 degrees to the equator – and, shortly thereafter, Gagarin began his passage across Hawaii, then out over the South Pacific. Following several requests, he was assured by the Khabarovsk station via long-range radio at 9:53 am that his orbit was satisfactory.

Minutes later, precisely on the hour, as he crossed the Strait of Magellan, Radio Moscow announced the electrifying news: “The world’s first spaceship, Vostok, with a man on board, was launched into orbit from the Soviet Union on 12 April 1961. The pilot-navigator of the satellite-spaceship Vostok is a citizen of the USSR, Flight Major Yuri Gagarin. The launching of the multi-stage space rocket was successful and, after attaining the first escape velocity and the separation of the last stage of the carrier rocket, the spaceship went into free flight on a round-the-Earth orbit. According to the preliminary data. . . ’’

The effect throughout the world, and particularly in the United States, was dramatic. Although it was known that the mission was underway virtually since its launch, and with certainty since Shemya confirmed Gagarin’s dialogue, and even though the imminence of the flight was not unexpected, the event sent shockwaves through the Kennedy administration. Before retiring to bed the previous night, the president had displayed a sense of foreboding and his science advisor, Jerome Wiesner, had gone so far as to prepare a statement for the press. Elsewhere, in Florida, NASA’s press officer John ‘Shorty’ Powers was awakened in the middle of the night by an alert journalist who had just heard of Gagarin’s launch. Powers, unfortunately, had not. With clear irritation in his voice and uttering words he would regret, he yelled down the phone: ‘‘What is this? We’re still asleep down here!’’ The journalist could not resist exploiting the figurative irony of Powers’ words. The United States and its own effort to put a man in space had indeed been caught offguard. Next morning came the front-page headline: ‘Soviets Put Man In Space. Spokesman Says US Asleep.’

It was not only the world that expressed shock and disbelief at Gagarin’s achievement; even those closest to him – his family – had little or no inkling of what had happened. Only his wife Valentina knew that he would be flying into space, although he had told her that the mission was planned for 14 April, so as not to worry her. He informed his parents that he was going on a business trip and, according to his sister, would be travelling ‘‘very far’’. Upon learning of the flight, his mother’s reaction was to buy a train ticket to visit her daughter-in-law in Moscow and help care for their children. His father, meanwhile, was working on the collective farm near Klushino and, after hearing that someone called Major Yuri Alexeyevich Gagarin was in space, he responded that it could not be his son, who was ‘‘only a senior lieutenant”. The enormity of what his son had done became apparent when he headed to the local soviet for more information and was quickly pushed onto the phone with a Communist Party official in Gzhatsk. Within hours, Alexei Gagarin and his sons were answering an endless stream of calls from journalists within and beyond the Soviet Union.

High above Earth, at 10:25 am, just off the coast of western Africa, near Angola, Vostok’s retrorocket fired automatically to begin its re-entry into the atmosphere. Gagarin would never need to touch his controls, nor open the envelope, nor worry about the three magic numbers. Eight thousand kilometres still remained to be covered before landing back in the Soviet Union. However, all did not go according to plan. Ten seconds after retrofire, as intended, the four metal straps holding the instrument section and the capsule together severed, but an electrical cable failed to separate. The cable contained a thick bundle of wiring which provided power and data to the capsule.

For ten minutes, the two remained connected, with the unneeded instrument section trailing behind and causing the capsule to experience wild gyrations as high as 30 degrees per second. The incident, which was not revealed by the Soviets, but which Gagarin hinted at in his state-sanctioned report, was potentially disastrous. The capsule was weighted in such a way that it would naturally rotate to point the thickest part of its heat shield into the direction of travel. If the instrument section did not separate cleanly, the capsule could not assume its correct attitude and properly bear the brunt of re-entry heating. Gagarin could burn alive.

Fortunately, at 10:35 am, as the spacecraft’s meteoric descent path neared Egypt, the cable finally burned through and separated the instrument section. After slinging the capsule away with a spin so severe that Gagarin almost lost consciousness, it finally attained aerodynamic equilibrium with its heat shield positioned accurately. It was later revealed that the complications arose when a retrorocket valve failed to close properly, allowing some fuel to escape from the combustion chamber. As a result of this loss, the engine cut off a second too early, slowing Vostok at a less – than-expected rate and preventing a normal shutdown command from being issued. In the absence of this command, the engine’s propellant lines remained open and pressurised gas and oxidiser continued to escape through the nozzle and served to induce the wild gyrations.

Although the engine was ultimately cut off by a timer, its lack of delivered thrust caused the spacecraft’s control system to scrub the primary sequence to separate the capsule from the instrument section. The notes of the cosmonauts’ physician, Yevgeni Karpov, auctioned by Sotheby’s in March 1996, revealed his concern and, indeed, analysts have speculated that – had the world known of these problems – the Sixties space race might have slowed dramatically.

Gagarin himself made one brief reference to the incident. “The craft began to revolve and I told ground control about it,’’ he wrote. “The turning I had worried about soon stopped… ’’ Little else would be known or even suspected for almost three decades. However, in his testimony before the top-secret State Commission on 13 April, whose panel included both Korolev and Kamanin, he described feeling the intensity of the capsule’s oscillations and an audible sound of ‘cracking’, possibly from the structure of Vostok itself or from the expansion of the thermal cladding material. Through the Vzor, he saw the bright crimson glow of ionised gases rushing past the capsule and would later estimate that the G forces exceeded 10 and ‘‘data on the control gauges started to look blurry. . . starting to turn grey in my eyes’’.

Eventually, as he heard denser air whistling past the capsule and saw blue – not black – sky outside, he braced himself for ejection. By this point, Vostok had crossed back into Soviet territory, on the Black Sea coast, near Krasnodar. Gagarin’s ejection procedure was supposed to be fully automatic, triggered when the on-board sensors registered an outside atmospheric pressure consistent with an altitude of 7 km. He may, however, have felt that the oscillations were too severe to risk it and it would appear that he initiated the sequence manually. With a tremendous roar and rush of air, the hatch above his head blew away and the ejection seat’s rocket propelled him from the capsule at terrifying speed. Protected from frigid high – altitude temperatures of -30°C by his suit, Gagarin descended to Earth; his main parachute opened successfully, followed by its backup, and the First Cosmonaut hit the ground under two canopies.

The location at which his feet touched terra firma, in a field some 26 km southwest of the town of Engels in the Saratov region, near Smelovka, are today marked by a 12 m obelisk and plaque, inscribed with the legend ‘Y. A. Gagarin Landed Here’. The formal marker was placed there on 14 April 1961. However, the historic nature of the event had already led someone to erect a small commemorative signpost on the spot, instructing potential trespassers not to remove it and announcing the time of his landing as 10:55 am Moscow Time. Less than two hours had elapsed since Gagarin’s launch from Tyuratam.

Tractor driver Yakov Lysenko heard, but could not see, the ejection sequence as a loud ‘crack’ in the sky. Seconds later, he saw the Vostok capsule descending under its own automatically-deployed parachute and immediately returned to Smelovka to raise the alarm. A hastily-assembled search party was greeted by what Lysenko would later describe as a ‘‘very lively and happy’’ Gagarin, who identified himself to them as ‘‘the first space man in the world’’. Farmer Anna Takhtarova also recalled the strange sight of the orange-clad cosmonaut telling them not to be afraid and asking for a telephone to call Moscow.

Shortly thereafter, the Soviet military, under General Andrei Stuchenko, arrived in force to take over the recovery effort. Gagarin had been promoted to the rank of major during his flight and was greeted as such by one of the local officers, Major Gasiev. “It was a complete invasion force,” Yakov Lysenko said later of the military’s arrival. “They didn’t allow us to get too close. They’re very strange people.” It was understandable, at least from Stuchenko’s perspective. He had already been told in no uncertain terms by an anonymous Kremlin official the previous day that on his head, literally, lay the responsibility to safely recover Gagarin. Stuchenko obviously wanted to leave nothing to chance.

The Vostok capsule hit the ground a couple of kilometres from the cosmonaut himself, since his high-altitude ejection had caused them to drift apart. For years, the spacecraft’s landing site was officially one and the same with Gagarin’s own, to avoid FAI suspicions that both had not touched down together. However, the Vostok site is known with certainty, thanks to a group of children who happened to be playing in a meadow near the banks of a tributary to the Volga River. They saw the capsule land. Schoolgirls Tamara Kuchalayeva and Tatiana Makaricheva described the dent it left in the soft earth and related how the boys clambered inside and began handing out and trying the tubes of space food. “Some of us were lucky and got chocolate,’’ Makaricheva recalled of the unusual mid-morning snacks. “The others got mashed potatoes. I remember tasting some [of this] and spitting it out.’’ Kuchalayeva agreed that she would not eat it again. Gagarin’s 108-minute adventure, it seemed, made him a hero not only for being the first to survive space, but also for being the first to survive the tastelessness of space food.