VEIL OF SECRECY

On a bleak, featureless expanse of steppe, some 200 km east of the Aral Sea, lies a tiny junction on the Moscow-to-Tashkent railway, known as Tyuratam. In the local

Kazakh tongue, its name is roughly translatable as the gravesite of Tyura, beloved son of the great Mongol conqueror Genghis Khan, whose medieval empire spanned much of Asia. According to some sources, the place began as an ancient cattlerearing settlement on the north bank of the Syr Darya River, although at least one Soviet-era journalist expressed preference for giving it a more modern origin, hinting at its foundation as recently as 1901 as an outpost to refill steam engines passing between Orenburg and Tashkent.

Its significance over the past half a century, though, cannot be disputed. It was from this sparsely populated region, five decades ago, that the first steps of a journey far more audacious, much longer and considerably more difficult than any the Great Khan could have envisaged were taken. It was this place that Gary Powers, following the line of railway tracks in his U-2 reconnaissance aircraft, tried to find when he was shot down in May I960. It was this remote corner of old Soviet Central Asia – a region swarming with scorpions, snakes and poisonous spiders, whose climate is characterised by vicious dust storms, soaring summertime highs of 50°C and plummeting wintertime lows of -25°C – that a young man, clad in a bloated, pumpkin-orange suit and glistening white helmet, sat atop a converted ballistic missile, defied all the odds and took humanity’s first voyage beyond the cradle of Earth.

One morning in April 1961, as five months of bitter snow and fierce, hurricane – strength blizzards yielded to the first murmurings of spring on the steppe, his kind achieved what had previously existed only in dreams. He rose from Earth, as Socrates once said, right to the top of the atmosphere and beyond and obtained a glimpse of the world from which he came. Contrary to some long-held expectations, the vista that Yuri Alexeyevich Gagarin beheld from 175-300 km high was not flat, nor could he discern any atlas-like lines dividing the countries, nor still, it is said, did he perceive any physical notion of God. Instead, he saw a beautiful, fragile oasis; a world iridescent with life and colour, encircled by what he described as “a very distinct and pretty blue halo’’ of an atmosphere, which almost merged into the blackness of space beyond. Flying at 28,000 km/h, in his journey of just 108 minutes, he somehow managed to plant fleeting images into his brain of rivers, islands, continents, forests and mountains. Never before had they been seen from so high by human eyes.

It is hardly surprising that the site from which he left Earth – known today simply as ‘Gagarin’s Start’ and still used to blast humans into space – was kept under wraps by the Soviet government. Indeed, in the early Seventies, when American astronaut Tom Stafford asked to visit the site in readiness for the joint Apollo-Soyuz mission, he met stubborn resistance. The Soviets’ desire to mislead and confuse prying westerners about this ultra-secret place was pursued to such an extent that even its name remained imprecise. Today, it is still variously known as Tyuratam, after the tiny railhead, or, more often, as Baikonur, which covers a wider and different geographical area. In fact, the town of Baikonur is more than 200 km from the launch base. For this reason, at a 1975 press conference, ABC News anchorman Jules Bergman expressed displeasure at the Baikonur name, pointing out that, despite its diminutive size, Tyuratam is actually closer.

|

Clad in space suit and helmet, the first man in space, Yuri Alexeyevich Gagarin, bids farewell to the genius who made his flight possible, Sergei Pavlovich Korolev. |

Whatever one’s preference, in February 1955 the site was chosen for a research and testing facility for the R-7 intercontinental ballistic missile; a missile developed by Sergei Korolev, the famed ‘chief designer’ of early Soviet spacecraft and rockets, originally to deliver huge warheads across distances of several thousand kilometres and, later, to send the first men into orbit. Assembly of the R-7 base – consisting of airports, rocket hangars, control blockhouses and the first of several colossal launch pads – was completed in a little over two years and, on 4 October 1957, one of these behemoths carried the world’s first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, aloft. Within a month, a living creature, the dog Laika, was boosted into space aboard Sputnik 2. However, not all missions were successful: two of Korolev’s Mars-bound probes exploded shortly after liftoff and in October I960 an R-16 missile misfired on the pad, destroying the launch complex in a conflagration which claimed the lives of almost 130 technicians, military officers, engineers and Marshal Mitrofan Nedelin. An American reconnaissance satellite, which overflew the site a day later, saw only a blackened smudge across the barren steppe. The awful truth of exactly what happened would not reach western ears for decades.

Ironically, only days before the R-16 disaster, Premier Nikita Khrushchev had boasted to the United Nations that Russia was producing intercontinental ballistic missiles ‘‘like sausages from a machine’’. On the fateful night of 23 October, just half an hour before its scheduled liftoff, the R-16 exploded, destroying the launch pad and breaking in half. Everyone in the vicinity of the inferno was either incinerated in the 3,000°C temperatures or succumbed to the missile’s toxic propellants. Marshal Nedelin’s remains were recognisable only from a Gold Star pinned to his uniform, whilst another man was identified from the height of his burned corpse. Although the R-16 was not directly connected to the R-7, which would be used for piloted missions, its loss caused an inevitable delay to the first manned space launch. In fact, many design organisations were involved with both the R-16 and R-7 and Nedelin himself chaired the State Commission for the man-in-space effort.

Consequently, in spite of its relative youth, the place already had historic and tragic attributes by the time Nikolai Kamanin, head of the newly-established cosmonaut team, arrived there in the spring of 1961 to oversee final preparations to send a man into space. The middle-aged Kamanin was one of the Soviet Air Force’s most distinguished generals, having led air brigades and divisions during the Second World War. In 1934 he had received the coveted Hero of the Soviet Union accolade for his role in the daring rescue of the icebound steamship Chelyuskin on the frozen Chukchi Sea. Throughout the Sixties, as the cosmonauts’ commander, Kamanin frequently disagreed with Korolev over differing policies, attitudes and requirements for the spacecraft and rockets, the men who would ride them and the often whimsical desires of the Soviet leadership. His memoirs are preserved in a series of quite remarkable diary entries, first published in 1995, which reveal a tough, bitter man who would blame his country’s loss of the Moon race on Soviet engineers’ unwillingness to give cosmonauts active control of their spacecraft.

Kamanin’s diaries paint a portrait of a man who fought fiercely for ‘his’ cosmonauts and show the close relationship between them during their time together on the isolated Kazakh steppe. However, he has also been described by space analyst Jim Oberg as an ‘‘authoritarian space tsar, a martinet’’ and by Soviet journalist Yaroslav Golovanov as ‘‘a malevolent person… a complete Stalinist bastard’’. Others, including cosmonaut Alexei Leonov, have proven more complimentary, seeing him as ‘‘very approachable” with a keen love of sports, especially tennis. Still, his brand of leadership, in most cases, successfully prepared the first generation of space explorers for their ventures into the heavens.

By the beginning of April 1961, wrote Kamanin, a number of obstacles remained to be overcome before a man could be launched. The basic design of his spacecraft had already been established and tested under the smokescreen name of ‘Korabl – Sputnik’ (‘Spaceship-Satellite’) which, between May 1960 and March 1961, had ferried dogs, rats, mice, flies, plant seeds, fungi and even a full-sized human mannequin famously nicknamed ‘Ivan Ivanovich’ into orbit. These missions evaluated everything from the spacecraft’s habitability to the performance of its ejection seat. Some proved to be dismal failures: the retrorockets of one mission fired in the wrong direction, sending the capsule into a higher orbit, while a July 1960 attempt exploded seconds after liftoff, killing its two canine passengers, Chaika and Lisichka. Others, notably the flight of the dogs Belka and Strelka, were hugely successful.

The latter were launched at 11:44 am on 19 August, accompanied by mice, insects, plants, fungi, cultures, seeds of corn, wheat, peas, onions, microbes, strips of human skin and other specimens. Two internal cameras provided televised views of them throughout the day-long mission. At first, the images showed the dogs to be deathly still – Belka, in particular, squirmed uncomfortably and vomited during the fourth orbit – prompting medical chief Vladimir Yazdovsky to gloomily recommend no more than one circuit for the first manned flight. The dogs’ return to Earth, however, was perfect and the capsule landed just 10 km from its intended spot in the Orsk region of the southern Urals. Belka and Strelka earned their places in history as the first living creatures recovered safely from orbit.

Upon examination, both were found to be in excellent condition, with no fundamental changes to their health. This data, together with the exemplary performance of the capsule’s systems, provided encouragement that a Soviet man could be launched before the year’s end. In fact, documentation from the Council of Chief Designers to the Central Committee of the Communist Party, produced around this time and finally declassified in 1991, revealed the formal timetable for sending a human pilot aloft. It recommended one or two more test flights in October and November I960, before attempting a manned shot in December. Signed by ministerial heads, rather than the standard deputy ministers, the document clearly reflected how important the man-in-space effort was to the Soviet leadership.

Known as ‘Vostok’ (‘East’ or ‘Upward Rising’), the machine that Yuri Gagarin, Gherman Titov and others would fly comprised a spherical cabin to house the cosmonaut and a double-cone-shaped instrument section. However, unlike the United States’ man-in-space effort, the true form of Vostok remained hidden from the world and would not be revealed in its entirety until a full-scale model appeared at the Moscow Economic Exhibition in April 1965. Until then, the Soviet Union’s propaganda apparatus continued to misinform western observers as to precisely what kind of spacecraft had placed the first man into orbit. Careful to maintain the ambiguity, Gagarin himself waxed lyrical, cryptically describing it as ‘‘more beautiful than a locomotive, a steamer, a plane, a palace and a bridge; more beautiful than all of these creations put together’’. His praise, though understandable, was not especially helpful. In the four years before Vostok was finally unveiled, the world could rely only on brief clips from Soviet documentaries and scenes from the Moscow Parades, which variously showed a contraption with an attached rocket stage, payload shroud and even, in the case of Vostok 2, a pair of short, stubby wings.

Today, at the Tsiolkovsky Museum in Kaluga, just south-west of Moscow, Vostok is presented for what it was: a 4,730 kg monster of a spacecraft, some 4.4 m in length and 2.4 m wide. Its capsule – nicknamed ‘the ball’ or ‘sharik’ (‘little sphere’) by the cosmonauts – comprised a little over half of its total weight, rendering it so heavy that not only a hefty parachute, but also an impact-cushioning rocket, would be needed to bring a man safely to the ground. Since this additional weight would have pushed it above the R-7’s payload capacity, Soviet designers incorporated an escape system to stabilise Vostok’s own descent by parachute, then allowing the cosmonaut to eject at a relatively low altitude of 7 km and land under his own canopy. During his descent, he would separate from his seat and touch down at about 5 m/sec. The Vostok, on the other hand, would impact roughly twice as fast, easily sufficient to injure the cosmonaut had he remained inside.

Questions of whether or not cosmonauts remained aboard their capsules throughout descent and landing were by no means insignificant. In order for such flights to be officially recognised for their achievements – specifically by taking the World Aviation Altitude Record – the Federation Aeronautique Internationale (FAI) required pilots to remain inside their machines from launch until landing. This would sidestep any accusation that they had been obliged to abandon their ships due to problems and ensure that their missions would be considered a successful ‘first’. The reality that none of Vostok’s fliers accompanied their capsules to the ground, but still made successful flights, was kept carefully hidden by the Soviets for many years.

In June I960, Korolev took Gagarin, Titov and 18 other cosmonauts to his OKB – 1 design bureau in Kaliningrad, north-east of Moscow, to see the first Vostoks in production. Their silvery spheres contained no aerodynamics, control surfaces or propulsion systems and, with their double-coned instrument sections, could only stand upright with the aid of metal frames. All of the cosmonauts were fighter pilots who could barely comprehend what they were seeing. All were enthusiastic to someday guide these machines through space, but none could understand how, without wings, they were supposed to do it.

Within the capsule, they found a tan-coloured rubber cladding, covering a myriad of wiring and piping, with little obvious instrumentation, save for a single panel containing switches, status indicators, a chronometer and a small globe representing Earth. Other systems would provide Vostok’s fliers with temperature, pressure, carbon dioxide, oxygen and radiation readings, as well as ticking off each circuit of their home planet. The bulky ejection seat occupied much of the cabin. At its foot was the ‘Vzor’ (‘Eyesight’) periscope to indicate that the spacecraft was correctly oriented for atmospheric re-entry. It consisted of a central view, encircled by eight ports; when Vostok was perfectly centred with respect to the horizon, all eight would be lit up. Within reach of the cosmonaut was a small food locker, providing up to ten days’ worth of supplies, and herein lay one of the problems that, in April 1961, stood in the way of future flights.

Attached to the base of the capsule was the double-coned instrument section, some 2.25 m long and 2.4 m wide and weighing 2,270 kg. Spread around the ‘waist’ between the two sections was a set of 16 spherical oxygen and nitrogen tanks for Vostok’s life-support system. At the bottom was the TDU-1 retrorocket, which employed a self-igniting mixture of nitrous oxide and an amine-based fuel. Capable of delivering a total thrust of 1,614 kg with a specific impulse of 266 seconds, the device would operate for 45 seconds with a 275 kg propellant load, slowing Vostok by around 155 m/sec to permit atmospheric entry at the end of a mission.

As long as the retrorocket operated without incident, the best opportunities for bringing the capsule back to Earth, and back to Soviet territory, were after one orbital pass – as was planned for Gagarin’s flight – or a full day later, somewhere in the midst of the 17th revolution. Admittedly, it could be fired at any other time, if necessary, but at the risk of bringing Vostok down within foreign borders or possibly

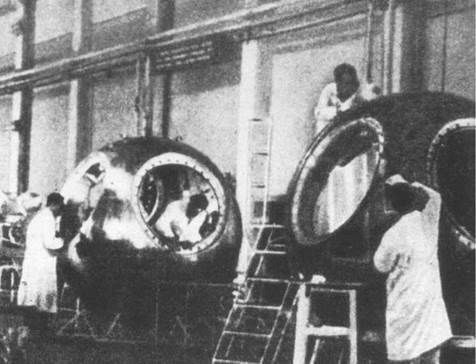

|

The Vostok spacecraft during construction in the assembly shop. |

into the sea. However, in the worst-case scenario that the retrorocket should fail to fire at all, the cosmonaut may have had to remain in orbit for up to ten days until his spacecraft naturally decayed from orbit. Although food and water were made available for such a long flight, the capsule’s lithium hydroxide canisters, meant to scrub exhaled carbon dioxide from the cabin, proved insufficient and in ground tests were expended within four days. Since Gagarin’s mission would last only a couple of hours, Kamanin felt that this would not preclude the ability to launch him in April 1961, but believed a new approach would be needed for longer flights.

Other obstacles had arisen during the Korabl-Sputnik missions, among them the 800 kg ejection seat. Although the ejection of a dog named Chernushka from the Korabl-Sputnik 4 spacecraft on 9 March 1961 and that of another dog, Zvezdochka, together with the life-sized mannequin Ivan Ivanovich, from Korabl-Sputnik 5 two weeks later, were successful, sea-based trials proved harder to quantify. Despite these misgivings, after three successful tests on the ground and from an Il-28 aircraft, coupled with the Korabl-Sputnik results, the seat was declared ready.

Months earlier, in September 1960, Korolev had submitted his proposal for a human flight to the Central Committee of the Communist Party and received approval. His original plan was to stage the mission before the end of that year, but the failure of Korabl-Sputnik 3 on 1 December – in which the dogs Pchelka and Mushka were incinerated, said the Soviets, when their capsule re-entered the atmosphere at too steep an angle – cast doubt on this schedule. (In reality, Korabl – Sputnik 3 had suffered a failure of its TDU-1 retrorocket and was remotely destroyed lest it land in foreign territory.) Another attempt just three weeks later uncovered a rare anomaly with the R-7 booster itself, whose third stage ran out of thrust halfway to space, although both of its canine passengers were ejected safely … landing thousands of kilometres off-course in a remote and inhospitable area of Siberia. Earlier in the year, another R-7 had exploded seconds after liftoff, ironically with many of the cosmonauts on hand to watch. “We saw how it could fly,” Gherman Titov said darkly. “More important, we saw how it blows up.”

By 7 April 1961, the final decision to go ahead with the mission was made and events moved rapidly. The Soviets were keenly aware that the United States’ first attempt to put a man into space was imminent, perhaps as soon as 28 April, although Kamanin firmly believed that Vostok would beat them. By this time, Gagarin and Titov had been selected as the prime and backup candidates for the flight. Their last few days were spent undergoing refresher classes on spacecraft and rocket systems, including the troublesome ejection seats. At one meeting, Kamanin reminded them of the option to fire the seat manually in the event of an emergency. Titov expressed total confidence in the seat and felt that worrying about it was a waste of time. Gagarin, on the other hand, offered a more considered response, perhaps so as not to embarrass Titov or the seat’s engineers, by pointing out that although his confidence was high, the manual option increased his chance of survival. He certainly knew how to play the game of cosmonaut politics.

It is difficult, though, to determine if one single event allowed the decision of Gagarin over Titov to be made. In their 1998 biography of Gagarin, Jamie Doran and Piers Bizony stressed that Kamanin himself had a hard time deciding between the two men. Only days before the mission, he noted in his diary that Titov completed his training more accurately than Gagarin, but that Titov’s “stronger character’’ put him in a better position to fly Vostok 2, which was planned to spend a full day in space. Others have hinted that Korolev simply liked Gagarin from their first meeting, that his calmness under duress and even his respectful removal of his boots before entering a Vostok capsule in the OKB-1 workshop may have played a part. Of equal, perhaps overriding, significance from the Soviet government’s point of view was the political need to favour a humble farmboy (Gagarin) over Titov, a more bourgeois teacher’s son. Even the simplicity of character between Gagarin and Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev, both of whom came from peasant roots, has been cited, together with Titov’s perceived lack of charm, reserved personality and ‘strangeness’ when spouting from memory reams of poetry or quotes from tsarist literature.

Certainly, an early evaluation of Gagarin’s personality, conducted in August 1960 by Soviet Air Force physicians and psychologists, was highly favourable of his ‘other’ talents. It read: ‘‘Modest: embarrasses when his humour gets a little too racy: high degree of intellectual development evident in Yuri; fantastic memory; distinguishes himself from his colleagues by his sharp and far-ranging sense of attention to his surroundings: a well-developed imagination: quick reactions: persevering, prepares himself painstakingly for his activities and training exercises, handles celestial mechanics and mathematical formulae with ease as well as excels in higher mathematics: does not feel constrained when he has to defend his point of view if he considers himself right: appears that he understands life better than a lot of his friends…” He seemed the perfect choice.

On 9 April, that choice was publicly made and filmed in colour by the official cameraman, Vladimir Suvorov. In reality, the decision had been made in secret the previous day, after which Kamanin had told both cosmonauts the outcome. Titov, he wrote, was visibly disappointed to have lost the flight, but both men mimed their way through ‘spontaneous’, though pre-rehearsed, speeches. Ironically, Suvorov’s camera ran out of film halfway through the acceptance speech, forcing Gagarin to repeat everything, word for word.

At 5:00 am Moscow Time on 11 April, the enormous R-7 booster, carrying the Vostok 1 spacecraft – simply labelled ‘Vostok’, so as to give no hint to the world that it might be the first in a series of missions – left the main assembly building in a horizontal position atop a railcar. Korolev, who knew it intimately as his ‘Semyorka’ (‘Little Seven’), accompanied it to the launch pad. Fuelled by liquid oxygen and kerosene, it consisted of a two-stage core, measuring 34 m long and 3 m in diameter and weighed 280,000 kg. Strapped around the core were four tapering boosters. Upon arrival at the pad, it was raised to a vertical position, ready for the arrival of its human passenger early the next morning. Liftoff was set for 9:07 am on 12 April, with plans calling for the jettison of the strap-on boosters two minutes into the flight, followed by insertion into low-Earth orbit at 9:18 am. Half an hour later, Vostok would orient itself in preparation for an automatic retrofire at 10:25 am, parachute deployment from the capsule at 10:43 am, ejection of Gagarin at 10:44 am and touchdown of both shortly thereafter. The entire flight would be shorter than one of today’s Hollywood blockbusters.

That night, the prime and backup cosmonauts stayed in a cottage close to the pad, their every toss and turn monitored by strain gauges fitted to their mattresses to allow physicians to determine whether they experienced restful sleep. The results indicated that they did, but Gagarin would later admit to Korolev that he hardly rested at all and spent much of his time trying to remain perfectly still in bed, so that he would be declared well prepared to fly the following morning. Months later, he would joke with Kamanin that the only reason Titov did not ride Vostok 1 was because he had rolled over in his sleep. Korolev also slept very little. His major concern was that the R-7’s third stage might fail during the ascent, perhaps dropping the spacecraft into the ocean near Cape Horn, an area notorious for its violent storms. Shortly before the launch, he demanded that a telemetry antenna be set up at Tyuratam to confirm the satisfactory operation of the third stage; if it worked as planned, the telemetry data would print out a string of ‘fives’ on tape, but if not, there would be a string of ‘twos’.

At 5:30 am on what is now universally known as ‘Cosmonautics Day’, 12 April 1961, Korolev and his head of medical preparations, Vladimir Yazdovsky, woke Gagarin and Titov from their slumbers. After washing, shaving and a breakfast of meat puree and toast with blackcurrant jam, physicians glued sensor pads onto their torsos and sent them to the spacecraft assembly building to don their pumpkin – orange suits. These had been designed by Gai Severin, the Soviet Union’s most accomplished manufacturer of attire and ejection seats for MiG fighter pilots. Severin utilised several key elements of earlier suit designs – including a tight fit around the legs to prevent blood from pooling into the lower torso and starving the supply to the brain – to protect Gagarin from the rapid acceleration of the R-7. The main layers of the suit, designed and built in only nine months, consisted of a blue – tinted rubber material, overlaid by the high-visibility orange coverall.

On launch morning, Titov donned his suit first in order to reduce Gagarin’s time spent overheating inside his own uncomfortable garment. As he continued his own suiting-up, Gagarin realised for the first time that he was – or soon would be – the most famous man on Earth. In his heavily-censored account of the mission, ‘The Road to the Stars’, published later in 1961, he recalled technicians offering him slips of paper and work passes on which to scrawl his signature. Titov beheld this and wished Gagarin luck, although he was disappointed and, even as he rode the bus to the launch pad, considered his role that day as hopeless. ‘‘He was commanding the flight and I was his backup,’’ Titov said later, ‘‘but we both knew, ‘just in case’ wasn’t going to happen. What could happen at this late stage? Was he going to catch the flu between the bus and the launch gantry? Break his leg? It was all nonsense! We shouldn’t have gone out to the launch pad together. Only one of us should have gone.’’ Vladimir Yazdovsky, who was also aboard the bus and gave him the order to remove his suit as soon as Gagarin was strapped inside Vostok, recalled Titov’s tension. Admittedly, Titov would fly Vostok 2 in a few months’ time, but history would not recall the Second Cosmonaut with the same clarity as the First.

Much tradition surrounds Gagarin’s trip to the pad, including, famously, his need to relieve himself through his suit’s urine tube against the tyres of the bus. Unable to share the going-away custom of kissing three times on alternate cheeks, he and Titov merely clanked their helmets together in a sign of solidarity. Korolev gave Gagarin a tiny pentagon of metal – a duplicate of a plaque flown on the Luna 1 probe two years before – and wryly suggested that, someday, perhaps the First Cosmonaut could pick up the original from the Moon’s dusty surface.

After reaching the top of the gantry, Gagarin manoeuvred himself into his ejection seat. Senior engineer Oleg Ivanovsky and chief test pilot Mark Gallai tightened his harnesses and plugged his suit hoses into Vostok’s oxygen supply. After giving him a good-luck tap on his helmet, Ivanovsky motioned for Gagarin to lift his faceplate to inform him of three significant numbers.

Since the beginning of their adventure in space, the Soviets had operated their machines through on-board systems controlled exclusively from the ground and, for a time, considered that manned missions should be undertaken in the same way. What would happen, wondered the medical experts, if a cosmonaut went mad in orbit, overcome by a profound sense of separation from his home planet, or even attempted to defect to the west, deliberately bringing his capsule down onto foreign soil? Guidance, it was decided, must be automatic.

However, if the cosmonaut’s sanity and devotion to the Motherland could be demonstrated, and if he needed to assume command, a six-digit keypad was provided to unlock Vostok’s navigation system, disengage it from the automatic controls and

allow him to fly the ship. The three-digit combination for the keypad would be radioed to Gagarin if ground staff considered him sane enough to take over. Yet the logic was questionable: what would happen if Vostok lost attitude control or its radio went dead and communications were impossible? Instead, a face-saving measure was adopted, whereby the three-digit code would be kept in a sealed envelope aboard the spacecraft, ready for the cosmonaut to open if needed. Gagarin’s ability to open the envelope, type in the numbers and activate the keypad would supposedly ‘prove’ that he had not lost his mind and was fully aware of his actions.

‘‘ft was a dangerous comedy,’’ Ivanovsky recalled later, ‘‘part of the silly secrecy we had in those days.’’ The envelope, though, had to be placed somewhere within easy reach, should he need to get to it in an emergency and a mentally unstable Gagarin could easily have opened it if he really wanted to do so. Mark Gallai, whose role included supervising the training of the Vostok cosmonauts, agreed, pointing out that all were qualified military pilots with experience of flying high-altitude, nighttime missions. The chance of them going mad was considerably less likely than suffering a radio failure. Consequently, betraying an official state secret and theoretically putting himself at risk of a lengthy prison spell, fvanovsky told Gagarin the three digits: 1-2-5. To his surprise, the cosmonaut smiled and replied that Kamanin had already given him the combination!

Assisted by Tyuratam’s chief of rocket troops, Vladimir Shapovalov, and two launch pad staff members, the next task for fvanovsky and Gallai was to seal Gagarin inside his capsule for liftoff. At this point, a problem reared its head. A series of electrical contacts encircling Vostok’s hatch should have registered a signal – known as ‘KP-3’ – to Korolev and his control team in the nearby blockhouse, informing them that it was secure. Furthermore, the signal was supposed to confirm that explosive charges around the hatch could jettison it at a millisecond’s notice in the event of an emergency and enable Gagarin to eject. On the gantry, the contacts seemed fine and the enormous hatch – which ‘‘weighed about a hundred kilos and was a metre wide,’’ according to fvanovsky – was manhandled into place and the laborious process of screwing its 30 bolts began. No sooner had they finished, the launch pad’s telephone rang. No KP-3 signal had been received, barked Korolev, and he demanded that they unscrew, remove, then reseal the hatch. After more fiddling, it was done. This time, thankfully, the KP-3 signal came back clearly.

ft was now less than 40 minutes away from the projected 9:07 am launch. fvanovsky, Gallai and the remaining personnel left the pad for the nearest control bunker. Vladimir Suvorov, determined to seize the most important photo opportunity of his career, stayed out in the open and would record some of the 20th century’s most remarkable imagery as the first man headed into space. Elsewhere, Gherman Titov was midway through stripping off his own space suit and his neckpiece was halfway over his head when the attending technicians disappeared to watch the launch. Meanwhile, alone in his tiny capsule, the young Soviet Air Force senior lieutenant, who had celebrated his 27th birthday and the birth of his second daughter a few weeks earlier, could scarcely have believed that his humble, peasant-stock roots in the small Russian village of Klushino could possibly have brought him this far.