Ablator Flights

Because so many unknowns still existed, the Air Force and NASA decided to conduct a thorough post-flight inspection of the entire airplane surface for each mission, and to monitor the ablator char depth and back-surface temperatures throughout the performance buildup. The ablator weighed 125 pounds more than planned and, taken with the expected increase in drag, the maximum speed of airplane was expected to barely exceed Mach 7.-333-

Pete Knight made the first flight (2-52-96) in the ablator-coated, ramjet-equipped X-15A-2 without the external tanks on 21 August 1967. The flight reached Mach 4.94 and the post-flight inspection showed that, in general, the ablator had held up well. The leading-edge details on the wings and horizontal stabilizers had uniform and minor charring along their lengths. A careful examination revealed only minor surface fissuring with all char intact, and good shape retention. The char layers were approximately 0.050 inch deep on the wing leading edge and 0.055 inch deep on the horizontal stabilizer-well within limits.-334-

The ablator details for the canopy and dorsal vertical stabilizer showed almost no thermal degradation, and local erosion and blistering of the wear layer were the only evidence of thermal exposure. The leading edge of the forward vane antenna suffered local erosion to a depth of 0.100 inch because of shock-wave impingement set up by an excessively thick ablator insert over the ram air door just forward of the antenna. The remainder of the leading-edge detail on the aft vane antenna showed "minor, if not insignificant degradation."!335-

The most severe damage during the flight was to the molded ablator detail on the leading edge of the modified ventral, which showed heavy charring along its entire length. "The increased amount of thermal degradation was directly attributable to the shock wave interactions from the pressure probes and the dummy ramjet assembly." Additional shock waves originated from the leading edges of the skids. The shock impingement had apparently completely eroded the lower portion of the detail, and very little char remained intact. However, it was difficult to ascertain how much of the erosion had taken place during the flight since sand impact at landing had caused similar, although much less significant, erosion during an earlier ablator test flight. Still, this should have been a warning to the program that something was wrong, but somehow everybody missed it.-336-

The primary ablative layer over the airplane experienced very little thermal degradation as the result of this Mach 5 flight. On the wings and horizontal stabilizers, only the areas immediately adjacent to the molded leading edges were degraded. These areas exhibited the normal random reticulation of the surface, there was no evidence of delaminating, and all material was intact. Some superficial blistering of the ablative layer was evident on the outboard lower left wing surface. Martin Marietta believed the blistering was most probably the result of an excessively thick wear-layer application. Not surprisingly, the speed brakes exhibited some wear, but there was no significant erosion or sign of delamination. The only questionable area of ablator performance was the left side of the dorsal rudder. A number of circular pieces of ablator were lost during the flight. A close examination of the area revealed that all separation had occurred at the spray layer interface, and significant additional delamination had occurred. The heavy wear layer, however, had held most of the material in place. The program had seen similar delamination during some of the earlier test flights and traced it to improper application of the material. It then changed the installation procedures to prevent reoccurrence.[337]

After the inspection, Martin Marietta set about repairing the ablator for the next flight. With the exception of the leading-edge details for the ventral stabilizer and the forward vane antenna, refurbishment was minimal. Only the wings and horizontal stabilizers had experienced any degree of charring, and technicians refurbished them by sanding away the friable layer. They did not attempt to remove all of the thermally affected material, and sanding continued only until they exposed resilient material. The canopy leading-edge detail required no refurbishment, but Martin lightly sanded its surface to remove the wear layer to minimize deposition on the windshield during the next flight.[338]

|

|

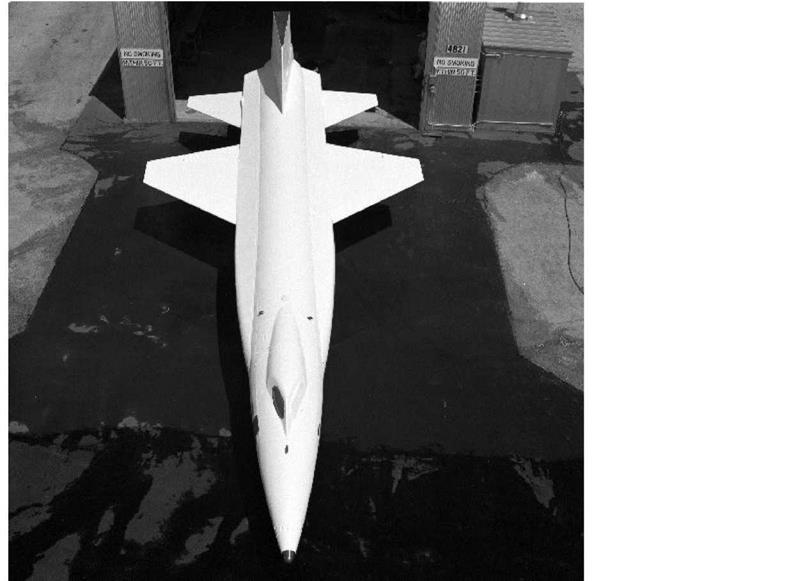

As it finally rolled out of the paint shop at the Flight Research Center, the MA-25S-covered X – 15A-2 was the polar opposite of what an X-15 normally looked like. Instead of the black Inconel X finish, the airplane had a protective layer of white Dow DC90-090. Actually, this was a relief to the pilots since the MA-35S has a natural pink color. (NASA)

Martin repaired local gouges in the main MA-25S ablator using a troweled repair mix and kitchen spatulas, eliminating most of the sanding usually required for the patches. Technicians sanded the speed brakes to apparent virgin material and resprayed the areas to the original thickness. They also completely stripped the left side of the dorsal rudder and reapplied the ablator from scratch using the revised procedure.-1339

Although the ablator around the nose of the airplane had experienced no significant thermal degradation, a malfunction of the ball nose necessitated its replacement, and the ablator was damaged in the process. Unfortunately, Martin had depleted the supply of ablator during the refurbishment process, forcing the use of a batch of MA-25S left over from a previous evaluation. For the final preparation the entire surface of the airplane was lightly sanded and a new coating of the replacement DC92-007 wear layer was applied.-349