Maximum Altitude

Joe Walker would fly the maximum altitude flight (3-22-36) of the program on 22 August 1963, his second excursion above 300,000 feet in just over a month. The simulator predicted that the X-15 could achieve altitudes well in excess of 400,000 feet, but there was considerable doubt as to whether the airplane could successfully reenter from such heights. A good pilot on a good day could do it, but if anything went wrong, the results were usually less than desirable. In order to

provide a margin of safety, NASA decided to limit the maximum altitude attempt to 360,000 feet, providing a 40,000-foot pad for cumulative errors. This might sound like a lot, but the flight planners and pilots remembered that Bob White had overshot his altitude by 32,750 feet. The X – 15 was climbing at over 4,000 fps, so every second the pilot delayed shutting down the engine would result in a 4,000-foot increment in altitude. The XLR99 also was not terribly precise – sometimes the engine developed 57,000 lbf, while other times it developed 60,000 lbf. An extra 1,500 lbf for the entire burn translated into an additional 7,500 feet of altitude. A 1-degree error in climb angle could also result in 7,500 feet more altitude. Add these all up and it is easy to understand why the program decided a 40,000-foot cushion was appropriate.12051

Walker had made one build-up flight (3-21-32) prior to the maximum altitude attempt in which he overshot his 315,000-foot target by 31,200 feet through a combination of all three variables (higher-than-expected engine thrust, longer-than-expected engine burn, and a 0.5-degree error in climb angle). Walker commented after the flight, "First thing I’m going to say is I was disappointed on two items on this flight, one was that I was honestly trying for 315,000, the other one was I thought I had it made on the smoke bomb on the lakebed. I missed both of them." Although he missed the smoke bomb on landing, it was well within tolerance. As for missing the altitude, the 40,000-foot cushion suddenly did not seem very large.12061

The flight was surprisingly hard to launch, racking up three aborts over a two-week period mainly because of weather and APU problems. On the actual flight day, things began badly when both the Edwards and Beatty radars lost track on the NB-52 during the flight to the launch lake, but both reacquired it 4 minutes prior to the scheduled launch time. The launch itself was good and Walker began the long climb to altitude. Although this was the first flight for the altitude predictor,

Walker flew the mission based on its results, changing his climb angle several times to stay within a predicted 360,000 feet. When the XLR99 depleted its propellants, X-15-3 was traveling through 176,000 feet at 5,600 fps. It would take almost 2 minutes to get to the top of the climb, ultimately reaching 354,200 feet.12071

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

||

![]()

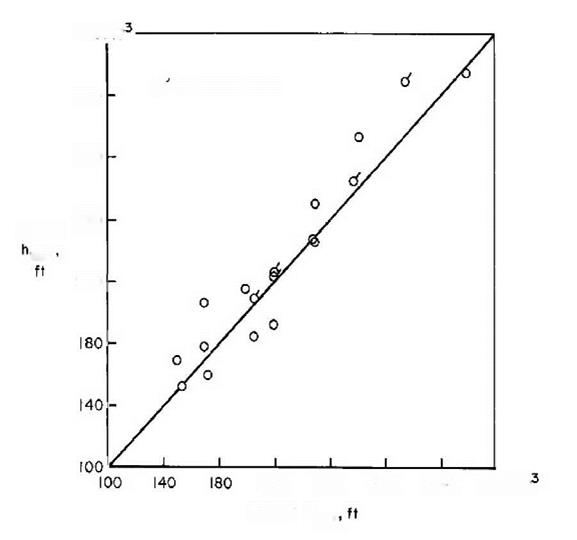

![]() Planned h

Planned h

It was not uncommon for X-15 altitude flights to miss their expected altitude. The X-15 climbed at over 4,000 fps, so every second that the pilot delayed shutting down the engine resulted in a

4,0- foot increment in altitude. The XLR99 also was not terribly precise – sometimes the engine developed 57,000-lbf; other times it developed 60,000-lbf. An extra 1,500-lbf for the entire burn translated into an additional 7,500 feet of altitude. A 1-degree error in climb angle could also result in 7,500 feet more altitude.

To give the reader a sense of what reentry was like on this flight: The airplane was heading down at a 45-degree angle, and as it descended through 170,000 feet it was traveling 5,500 fps-over a mile per second. The acceleration buildup was non-linear and happened rather abruptly, taking less than 15 seconds to go from essentially no dynamic pressure to 1,500 psf, then tapering off for the remainder of reentry, and reaching a peak acceleration of 5 g at 95,000 feet. Walker maintained 5 g during the pullout until he came level at 70,000 feet. All the time the anti-g part of the David Clark full-pressure suit was squeezing his legs and stomach, forcing blood back to his heart and brain. Walker said that "the comment of previous flights that this is one big squeeze in the pullout is still good." The glide back to Edwards was uneventful and Walker made a perfect landing. The flight had lasted 11 minutes and 8 seconds, and had covered 305 ground miles from Smith Ranch to Rogers Dry Lake. Although Walker had traveled more than 67 miles high, well in excess of the 62-mile (100-kilometer) international standard supposedly recognized by NASA, no astronaut rating awaited him. This was apparently reserved for people who rode ballistic missiles at Cape Canaveral, and it would take 42 years to correct the oversight.-1208!

By the end of 1963, the program had gathered almost all of the data researchers had originally desired and the basic research program was effectively completed. The program would now push into the basic program extensions phase using X-15A-2 to gather similar data at increasingly high speeds while the other two airplanes continued the follow-on experiments. The basic program extensions were a set of experiments that had not been anticipated when the Air Force and NASA conceived the basic program. Some were truly follow-ons to issues that were uncovered during the basic program; others were the result of new factors, such as the increased capabilities of the modified X-15A-2. In general, researchers continued all of the original research into aerodynamics, structures, and flight controls for the rebuilt airplane. The FRC paid for many of the experiments from general research funds, not from a separate appropriation from Headquarters or Congress.-1209

Despite the progress and future plans, there was no uniform agreement that the X-15 program should continue. At least privately, several officials (including Paul Bikle) argued that the value of the projected research returns was not worth the risk and expense, and that the program should be terminated at the conclusion of the basic research program, or as soon as the X-15A-2 had completed its basic program. This body of opinion was the same that had initially led NASA to argue against modifying X-15-2 into the advanced configuration. However, by this time the X – 15A-2 was well under construction and researchers had proposed an entire series of follow-on experiments, making it unlikely that the program would be terminated any time soon.-129

Although the point would be moot after the Department of Defense canceled the Dyna-Soar on 10 December 1963, at the end of 1963 the X-15 program was making plans for four unnamed future X-20 pilots to make high-altitude familiarization flights in X-15-3 during the first half of 1964. Several of the Dyna-Soar pilots had already flown the X-15 simulator in preparation.-121